Warning: nerdy blog ahead.

Last week, I traveled to Toledo, Ohio—the belly of the beast in terms of Lake Erie’s harmful and toxic algae bloom. I went to hear the latest on research on harmful algae blooms. Toledo is very familiar with the issue. In the summer of 2014, the city had a state of emergency when toxic blue green algae shut down the city’s water systems. For three days, 400,000 people were left without safe drinking water.

Since then, organizations, governments, universities and researchers in Ohio and across the Lake Erie basin have been working hard to study harmful algae, and prevent any future disasters. The better we understand the science, the more action we can take to protect our drinking water, ecosystems, and economies that rely on the lake.

Lesson learned: we can immediately reduce the severity of algae blooms

For me, this years’ “State of the Science” conference on Lake Erie algae blooms was especially inspiring. First of all, I met so many (over 350) people dedicated to action on algae, which was awesome. Second, I found out that the new Governor of Ohio Mike DeWine has committed hundreds of millions of dollars to tackling algae blooms through the H2Ohio program.

By far, the very best moment was when a group of scientists stood up in front of a giant hall filled with people. They said “We can have an immediate impact on the size of the bloom” by keeping phosphorus on the land and out of the water. Dr. Richard Stumpf with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) said this year’s bloom is evidence that we can see very quick results from swift efforts to keep phosphorus out of the water.

What we do on land impacts our water

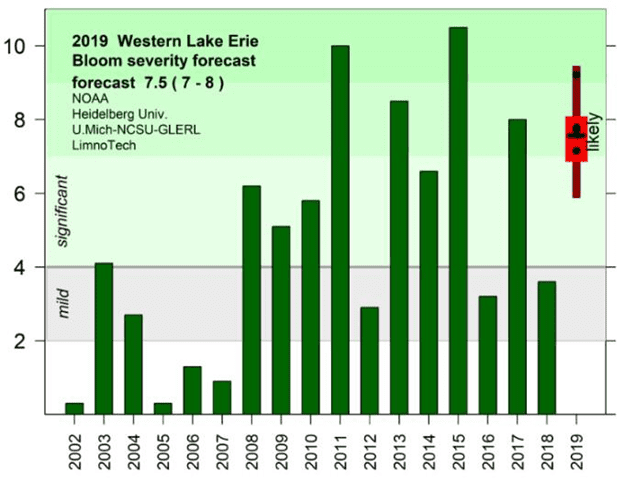

Last fall and this spring, there was a lot of rain around the Lake Erie basin. So much rain, in fact, it was difficult for farmers to plant at the same rate, especially in Ohio. As a result, less phosphorus was used. The modelling tells us that for the amount of rainfall we had, we should have seen about 30 per cent more phosphorus entering the lake. Since there was less pollution going into streams, rivers, and eventually Lake Erie, this year’s algae bloom was held back at a predicted 6-8 on the severity scale of 1-10. It could have easily been a level 10 bloom, similar to what we saw on the lake in 2011 and 2015.

Before now, many scientists, and the broader Lake Erie community, thought it could take years or even decades for a reduction in phosphorus to translate to a smaller bloom. This is because there is already so much phosphorus pollution in the system. However, what happened this year shows us that while legacy phosphorus is one piece of the puzzle, we can have an immediate impact on improving the lake’s health by taking action immediately.

Next steps: Where do we go from here to save Lake Erie?

Even though 30 per cent doesn’t sound like a lot, and the bloom this year was still massive, the lesson is it could have been much worse. As climate change brings more frequent and intense rainfall, we can expect that very rainy springs will become the new normal. This means more phosphorus entering the lake every season, causing bigger blooms unless we take strong action immediately. The Ontario and federal governments need to implement their action plan for Lake Erie, and increase their investments in lake-saving technologies. The good news is that the data over the past year shows us that we can make an immediate difference by keeping pollution out of our waters. Now we must get to work.