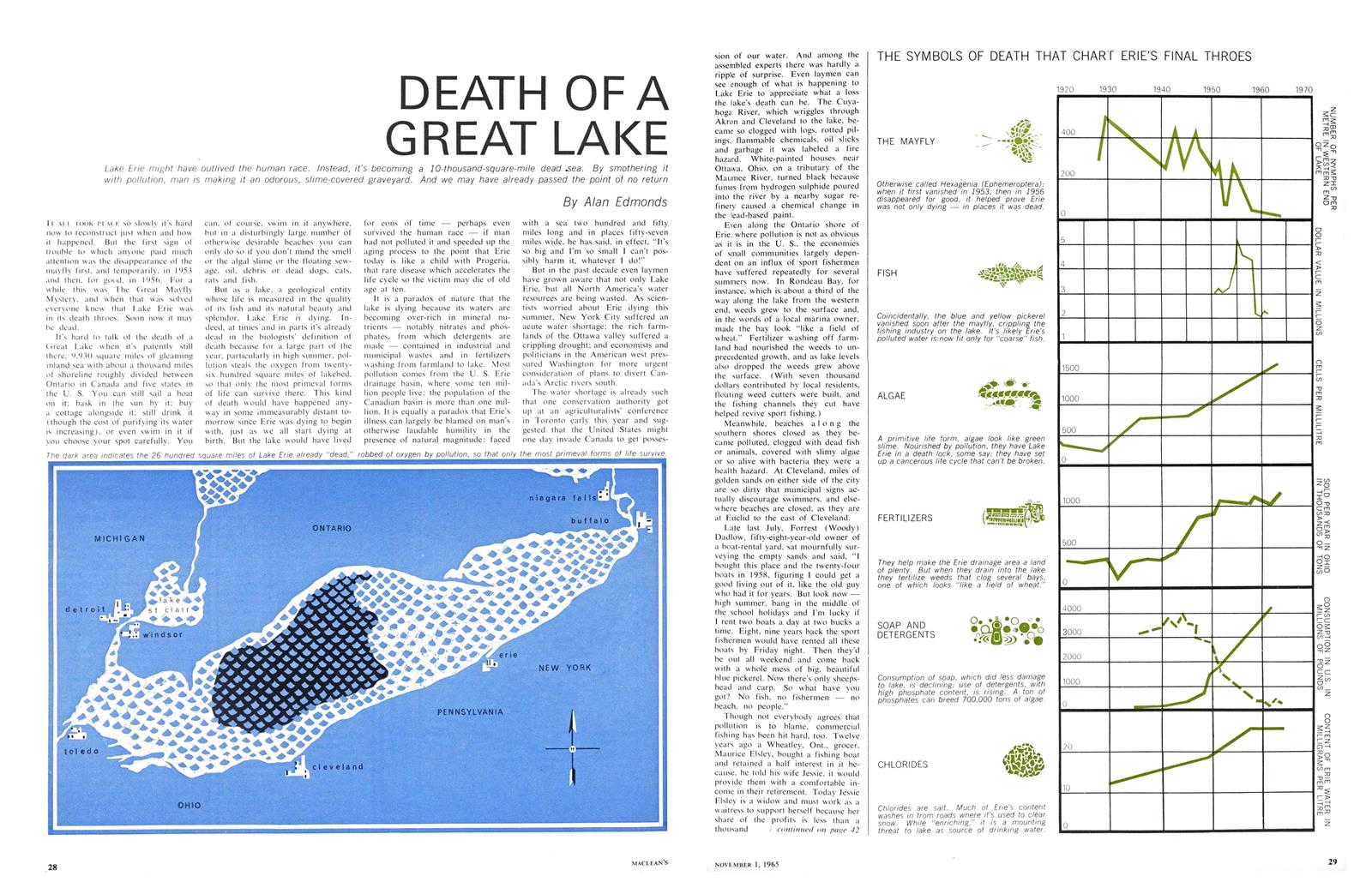

For Nandita, drinking tap water was unthinkable: she knew that being careless and not boiling the water could be deadly. It was out of necessity that Nandita initially became interested in water quality. She took a particular interest in Kolkata’s wetland system at the edge of the city. This area works as a natural purifier for the city’s waste, protecting the river Ganga. It is also an economic hub due to its aquaculture.

When thinking about where her love for science comes from, Nandita figures that her Dadu (grandpa) had a lot to do with it. Nandita’s grandfather studied physics but never worked in the field. Instead, he worked in an insurance company to support the family, but he never lost his passion for science. Some of Nandita’s fondest childhood memories are doing science experiments at home with her grandfather.