In 1806, Michelle’s great-great-great-great-grandfather Dennis Calico was born into slavery on a plantation in Tennessee and subsequently sold to the Robbins’ plantation. His new master offered Dennis freedom if he married Jane (who the master had children with) and took the name Robbins. Dennis and his new family came to Canada’s Elgin Settlement in Buxton, Ont., using the Underground Railroad — the largest anti-slavery freedom movement in North America, used by enslaved African Americans to escape into “free states” and/or British North America (Canada). This “railroad” involved a network of secret routes and safe houses established in the U.S. during the early to the mid-19th century. Somewhere between 30,000 and 40,000 total “fugitives” escaped to Canada.

MEET THE PEOPLE

- Patricia – Pelee Island

- Heidi – Pigeon Bay

- Carrie Ann and Janne – Leamington

- Lisa – Leamington

- Mohamad – Leamington

- Sandra – Leamington

- Anthony – Kingsville

- Todd – Wheatley

- Ken – Shrewsbury

- Michelle – North Buxton

- Todd – Port Stanley

- Julia – Stratford

- Nandita – Waterloo

- Charlie – Guelph

- Mat & Melissa – Norfolk County

- John & Jan – Long Point

- Holly – St. Williams

- Gregary – Niagara

- Fred – Port Colborne

- Robin – Oshawa

Michelle – North Buxton

Story and images by Colin Boyd Shafer

Michelle is a fifth-generation Canadian. On both her mother’s side of the family (Handsor) and her father’s side of the family (Robbins), her ancestors migrated to Canada to escape slavery in the United States.

Michelle’s tattoo of the North Star represents what guided her ancestors and many others north to Canada — “the promised land.” Robbins, Michelle’s last name, is the name of her ancestor’s “master.”

Michelle finds these shackles made for a child to be the most impactful item on display at the Buxton National Historic Museum. “My child would have had to wear these. That’s why it is so powerful to me as a descendent of slaves and as a parent.”

For many people escaping slavery, crossing Lake Erie was one of the last steps to finally achieving freedom.

Looking out over the lake towards Ohio, Michelle can’t help but think of how many people lost their lives as they tried to cross the lake and find safety and freedom.

(left) In front of the Buxton National Historic Museum stands a wooden statue of Reverend William King, the man who started the Elgin Settlement with 15 of his inherited slaves (two of them, Solomon and Eliza, stand on the right of King’s statue). (right) Michelle stands amongst an exhibit in the museum opened in 1967 to collect, preserve, exhibit, and interpret historical artifacts related to the community settlers and their descendants.

The Elgin (Buxton) Settlement, founded in 1849, became home to approximately 2,000 people of African descent by the mid-19th century. Like Michelle’s ancestors who settled there in 1866, the people who arrived in this farming community found opportunities they had never had before.

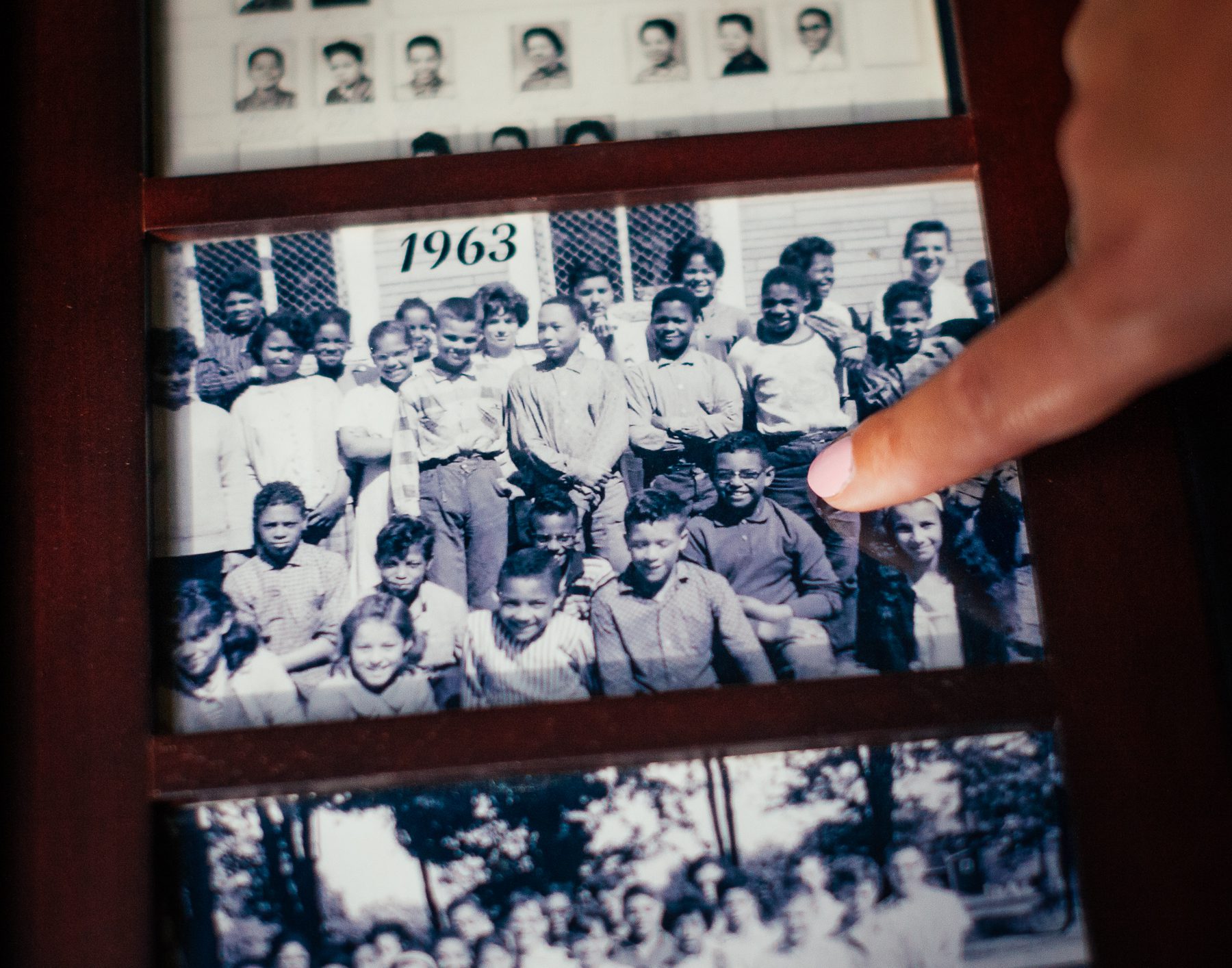

(top) Michelle’s daughter Layla (age nine) sits in SS #13, the local school that opened in 1861, where Michelle’s ancestors studied. It is the only known early Underground Railroad school to still exist in Canada.

(bottom right) A school photo of Michelle’s father in 1963 (around the same age as Layla is now).

Many people who sought refuge in Buxton ended up returning to the United States after 1865 (the passing of the 13th Amendment/abolishment of slavery). Like the Robbins, some families stayed in Buxton, where they continue to live today as generational farmers.

Michelle’s father Mike still farms beans, corn, and wheat on their family farm.

In 1924, by the pear tree in the pasture fields of Charles & Constance Robbins (Michelle’s great-grandparents) that still stands there today, Buxton had its first “homecoming.” With an idea brought to the community by Reginald & Minnie Robbins, the event intended to bring back former residents who had relocated to other parts of Canada and the U.S. to visit the community. Today, descendants of former slaves see the event as a pilgrimage “home.” What started as a one-day event has evolved into a full four-day celebration where people celebrate their heritage through music, conferences, and various activities in the community.

Michelle looks out at the original pear tree — the site of Buxton’s first homecoming.

Michelle describes Buxton as the most welcoming community you could ever visit. "Everybody knows everybody, and a lot of us are related.” While she may live in Chatham, Ont., her heart is in Buxton.

"When I see that North Buxton sign, I know I am home."

All of Michelle’s ancestors on the Robbins side are buried in the North Buxton Cemetery. Michelle’s grandfather Charles taught the family how to look after horses, and Michelle grew up grooming, feeding, and riding.

Michelle is worried about the lake’s preservation and wishes more people cared about its protection. As a child, Michelle spent a lot of time in Port Alma, exploring the shoreline by her school friend’s house. Today, most of the coastline she used to enjoy is completely gone due to erosion. There are special places to Michelle’s childhood that she wants to share with Layla, but they are either gone or blocked by caution signs.

(left) Michelle as a child with her sister and cousin at Burns Beach. (right) Michelle’s daughter stands on the eroded shoreline and what remains of Burns Beach.

“I want to be able to have the same surroundings for generations to come. I want my grandkids to play in the water and have it be safe for them. I want to give the same great memories I have of Lake Erie to my grandchildren and great-grandchildren.”

Michelle holds her family’s oldest heirloom. This chair now sits in the Colbert-Henderson House (a house from the early settlement built in 1852, that now sits on the museum grounds).

In the future, when people look out across Lake Erie, Michelle hopes they will reflect on its history as a symbol of hope and freedom for people fleeing. She also hopes future generations will learn more about the Black history explicitly tied to the lake and region, and Canadian Black history in general.

“I feel like now is the perfect time for people to commit to learning more.”

Read More

STORIES FROM THE LAKE

Anthony – Kingsville

Take Action

Lake Erie and the millions of people who rely on it for their drinking water, local jobs, and so much more need your help.

The health of Lake Erie continues to decline. Action is needed more than ever to restore its health for current and future generations.

You can make a difference. Here’s how you can help protect the lake and support the people who are closely connected to it.

EXHIBITION BY: documentary photographer COLIN BOYD SHAFER in collaboration with ENVIRONMENTAL DEFENCE