“Growing up on the farm and helping my father over the years, that’s where my interest in agriculture started.”

MEET THE PEOPLE

- Patricia – Pelee Island

- Heidi – Pigeon Bay

- Carrie Ann and Janne – Leamington

- Lisa – Leamington

- Mohamad – Leamington

- Sandra – Leamington

- Anthony – Kingsville

- Todd – Wheatley

- Ken – Shrewsbury

- Michelle – North Buxton

- Todd – Port Stanley

- Julia – Stratford

- Nandita – Waterloo

- Charlie – Guelph

- Mat & Melissa – Norfolk County

- John & Jan – Long Point

- Holly – St. Williams

- Gregary – Niagara

- Fred – Port Colborne

- Robin – Oshawa

Charlie – Guelph

Story and images by Colin Boyd Shafer

Charlie grew up on a farm in eastern Ontario’s Prescott County.

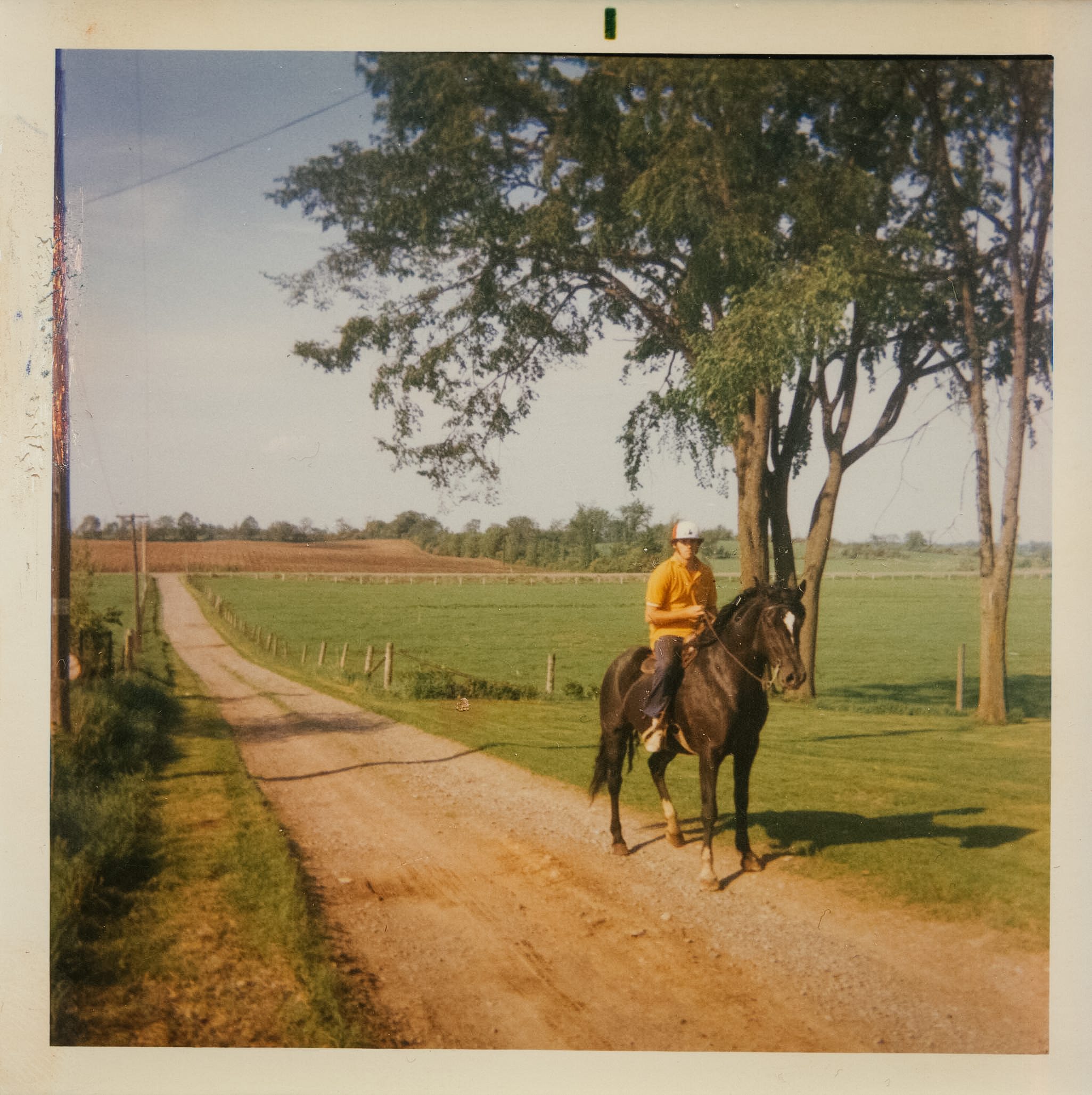

(left) Charlie in 1970 at the age of 20, with his father DJ, who farmed all his life. (right) Charlie on a horse at the farm. “We always had cattle, and so it was handy to have a couple of horses.”

Charlie studied agriculture at university and has worked all his life in the agricultural field. In 2002, as a response to the Walkerton water crisis, Charlie, as the director of the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs, led a team that created the Nutrient Management Act — Ontario’s first framework of this sort.

In 2007, after retiring, Charlie started working with farm organizations, consulting on best management practices.

The Thames River in downtown Chatham, Ont. The river eventually feeds into Lake St. Clair, which connects with Lake Erie.

As a consultant, Charlie works primarily in the Thames River basin, a priority watershed with more than 200 kilometres of intense agriculture production. This reality delivers a substantial amount of phosphorus to Lake Erie.

“The amount of phosphorus that is lost from our farms is minimal on a per-acre basis. But when you are dealing with millions of acres, it adds a significant amount of phosphorus to the lake that becomes a key part of the algae bloom creation.”

Charlie explains how it is usually in the winter and the early spring, not when the crops are growing, that an agricultural area loses the most phosphorus in its water runoff.

(top left) Charlie looking at soy, a common crop in the Thames River basin. (top right) A large part of his projects is examining how we can reduce the loss of nutrients through runoff events. (bottom) Agricultural fields in the flat Thames River basin have a tile system that empties the water out into drains (see black pipe). The water and nutrients in these drains eventually make their way into the Great Lakes system.

One thing that can help with nutrient loss is if farmers plant ground cover. Cover crops like oats, barley, clover, oilseed radish (often a mixture of these plants) help keep the soil in place, which in turn, keeps more phosphorus in place. A large amount of the phosphorus that gets into the drains happens after significant rain events and the resulting erosion, and this can be prevented with cover crops.

Phosphorus reduction is an essential focus of the projects Charlie works on. At his Roesch's Farm demonstration site, east of Chatham, Ont., they test different ways of absorbing and removing phosphorus from the environment. They are currently trying a synthetic product created by researchers from the University of Windsor that mimics the absorbent quality of tomato roots.

At the Roesch's Farm demonstration site, east of Chatham, the farmer rotates seed corn, soybeans, and small grains like wheat or barley. Every year, the farmer applies manure to the flat field, and any water that flows off goes through its tile drainage system (underground pipes). Charlie is there to access the phosphorus loss and see whether they can capture the phosphorus from the tile drain waters before it gets into the drain.

“Lake Erie, and the other Great Lakes, are shared resources of freshwater important to all of our lives.”

Some of Charlie’s best memories have been at the various conservation areas and beaches along Lake Erie. He made sure his kids had an opportunity to enjoy the lake as they grew up. Charlie wants his grandchildren and future generations to continue to enjoy the lake.

Charlie calls the changes he has witnessed to the lake in both water quality and level "drastic".

At the Merlin Road/ Jeannette Creek demonstration site, Charlie is testing out ways to capture and remove phosphorus from agriculture water from tiled fields that are being pumped into Jeanette Creek.

A decade ago, the lake level was at a low point and the beaches, like at Long Point, where Charlie often took his family, were extended with sand bars in the water. Now that has flipped completely, and a lot of those beaches are gone.

Water levels and erosion are important issues affecting Lake Erie. Still, Charlie believes they get the most attention because of short-term economic interests (like property development). In contrast, water quality is a long-term issue that doesn’t get enough and deserves more attention.

(top) A frog sits on a piece of styrofoam in an agricultural drain. (bottom) Jeannette Creek empties into the Thames River, which empties into Lake St. Clair and on to Lake Erie. Charlie emphasizes how even though agricultural lands might be far from the lake, it doesn’t mean that nutrients they release won’t eventually make their way to them.

In 2018, Charlie was asked to participate in an agricultural session at a Great Lakes-related event. While there, Charlie realized how few people wanted to talk about water quality; they were mostly interested in water levels.

“I would say the overwhelming interest was about water levels. People were concerned about marinas, losing docks, the lack of beaches. That all trumped water quality issues.”

Charlie explains how we only have a limited capacity to adjust water quantity through the dam system: “It’s not something you turn on a dime like draining a pool. It takes a lot of time. Nature fluctuates these water levels, and there is not much that can be done about it.”

Charlie hopes people will pay more attention to the seriousness of this resurgence of toxic blue-green algae blooms.

The Toledo water crisis of 2014 left people there without safe drinking water. Charlie doesn’t want the same thing to happen to the communities he works in.

“Events like the Toledo water crisis should be a turning point in terms of society realizing that we have to do something different.”

Charlie explains how the Thames River, which runs through Chatham, has an already slow water flow that can be significantly reduced by western winds. This pace, along with heat, makes the summer months particularly susceptible to algae blooms. A couple of years ago, Charlie remembers when for 72 hours, the entire river turned green with toxic blooms.

“Like any other challenge, it’s going to be a difficult road ahead to rebalance the lake's ecology and it will require efforts from municipalities. We have to go beyond the regulatory limits in terms of the relief of phosphorus. To fix this problem, we will need to go further.”

Charlie hopes that his projects can help farmers reduce the amount of nutrients that agricultural fields release into the drainage water that eventually makes its way into Lake Erie. In effect, these efforts can help reduce the occurrence of toxic algae blooms and all the adverse effects they have on the lake’s ecosystem and people.

Read More

STORIES FROM THE LAKE

Robin – Oshawa

Take Action

Lake Erie and the millions of people who rely on it for their drinking water, local jobs, and so much more need your help.

The health of Lake Erie continues to decline. Action is needed more than ever to restore its health for current and future generations.

You can make a difference. Here’s how you can help protect the lake and support the people who are closely connected to it.

EXHIBITION BY: documentary photographer COLIN BOYD SHAFER in collaboration with ENVIRONMENTAL DEFENCE