Carrie Ann’s great-great-grandfather, George Maxon Girardin, worked out on Point Pelee towards the end of the 1800s. He was a volunteer rescuer—nicknamed “monkey man” because of his small size —who would go out on a rope to big ships that had hit the ground off Point Pelee. Girardin was the last person buried in the Point Pelee Cemetery in 1948. Burials were stopped there because of the marshy waters coming in and taking over the graves. Sadly, when his wife passed away, she wasn’t allowed to be buried next to him.

MEET THE PEOPLE

- Patricia – Pelee Island

- Heidi – Pigeon Bay

- Carrie Ann and Janne – Leamington

- Lisa – Leamington

- Mohamad – Leamington

- Sandra – Leamington

- Anthony – Kingsville

- Todd – Wheatley

- Ken – Shrewsbury

- Michelle – North Buxton

- Todd – Port Stanley

- Julia – Stratford

- Nandita – Waterloo

- Charlie – Guelph

- Mat & Melissa – Norfolk County

- John & Jan – Long Point

- Holly – St. Williams

- Gregary – Niagara

- Fred – Port Colborne

- Robin – Oshawa

Carrie Ann and Janne – Leamington

Story and images by Colin Boyd Shafer

“Our family has always been here.”

Carrie Ann and Janne are members of Caldwell, a First Nations band government with traditional territory ranging from the Detroit River to Long Point. Carrie Ann can trace her ancestry in the region back seven generations. Stories have been passed down through the family of how once, a long time ago, people would walk from the tip of Point Pelee out to Pelee Island.

“Point Pelee and Pelee Island are the heart of our ancestral territory.”

“Sweetgrass, for us, represents kindness. Its braids represent the hair of mother earth.” Carrie Ann explains how the sweetgrass is prepared using 21 blades — each of the three braids made of seven blades. The first section of seven blades represents the seven generations behind, the second, the Seven Sacred Teachings, and the third, the seven generations ahead.

Carrie Ann stands in Point Pelee Cemetery where her great-great-grandfather is buried.

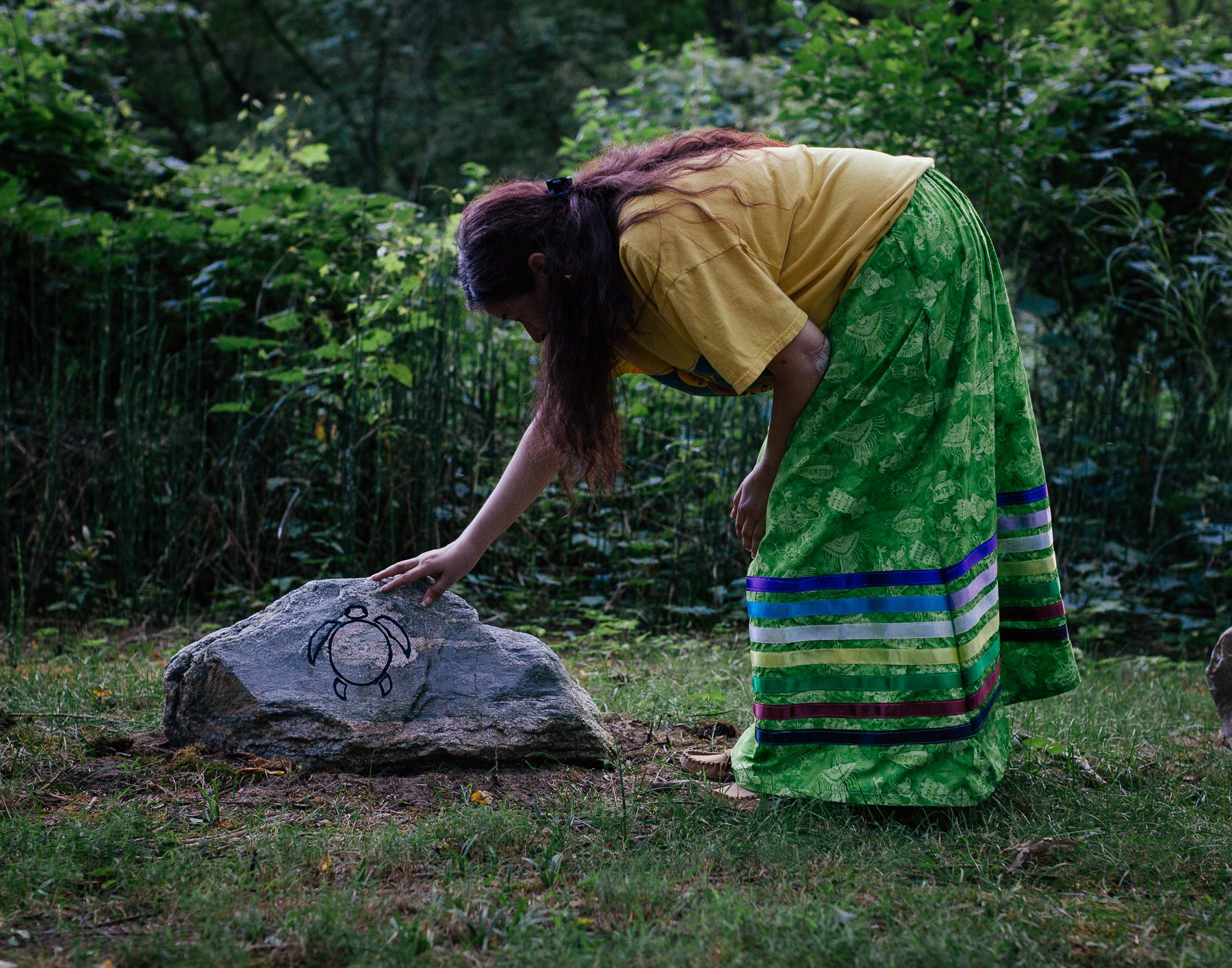

In 2018, Carrie Ann led a project to replace the white Christian crosses over unnamed indigenous graves in Point Pelee Cemetery. “We wanted to have something more connected to our culture.” They replaced the crosses with stones, which Carrie Ann explains are referred to as “grandfathers” in her culture. Each stone has a different symbol important to her people painted on it —a wolf, bear, turtle, eagle, or a feather.

Carrie Ann’s mom Janne is the baby in the middle, held by her brother Isaac Peters the III. The family is in front of Janne’s Uncle Ed’s house.

Carrie Ann’s mother, Janne, remembers her childhood in Leamington, Ont. fondly. It was a very different place back in the 1950s.

“When I was a kid, we had the iceman, the breadman, and the milkman.”

In the 1950s, nobody had refrigerators. Janne’s family had to get ice for their icebox from the “iceman.” The ice came from blocks cut from Lake Erie’s ice collected in the winter.

When Janne was a child, learning to swim was not a choice.

“You got thrown off the dock, and it was either sink or swim. I learned how to dog paddle really quick! The water was what we kids lived for. It was our playground.”

Janne remembers the water back then being so clean and clear and how the lake’s bottom was pure sand. She loved doggy-paddling along the shore, looking for shiny stones.

“We could be swimming and splashing and dunking each other. Back then, you would get water up your nose or down your throat, and you didn’t have to worry about getting sick. Now you get water down your throat, and you are running to the hospital. Back in those days, they didn’t have boil alerts on the water or signs posted on the beach saying you couldn’t swim.”

Janne and her friends would be in the water from the first of April until “it got so cold you couldn’t stand it.” Janne remembers how her sister’s cannonballs off the dock would scare all the fishermen’s fish away. Janne loved climbing up on the rocks, and just as a wave came in, she would jump into it and let it take her out. “We got heck for doing it, but nobody ever got hurt.”

Janne’s father Isaac Peters II (on the right) was a hunter. Janne remembers how they would share the meat and tan the hides to sell. For the last five years, Isaac’s granddaughter, Carrie Ann, has participated in the deer reduction hunt at Point Pelee National Park.

As a teen, Janne loved going down to a little restaurant on the lakefront (that is gone now) — where she could listen to the jukebox, drink coke, and share french fries with a friend. “That’s all we could afford, but it was carefree in those days.” Any money she had was from working out in the farm fields picking beans, strawberries, or peaches. From age 11, Janne worked either for her uncle or other farmers, after school and in the summer. She remembers how she would take her pay at the end of the summer, go to Zellers, and buy school supplies. Sunday, during the summers, was her one day off from working in the fields. She would swim, fish, and cook the fish right there on the beach with her family.

Janne’s mom June fishing at Point Pelee. Janne remembers how her mother loved to fish but was afraid of the water. “Mom would never go into the lake past her ankles.”

Many aspects of Janne’s childhood were carefree. Still, looking back, Janne sees all that was withheld from her - her traditional culture and language.

“Us kids were never taught our language. We weren’t allowed. My grandparents refused to teach us, and they forbid my father from teaching us. Our aunts and uncles were told to watch their language when they were around us kids. Everyone was afraid that we would be taken to residential schools if we spoke our language.”

Despite her family’s attempts to keep their culture and language from Janne, she listened and tried her best to piece together what she could.

“When I was a kid, believe it or not, I didn’t talk that much. Now you can’t get me to shut up! When my aunts or uncles or grandma or grandpa were around, I always listened carefully. Every once and a while, they would talk in our language. I didn’t know what they were saying, but I would guess and absorb it.”

This house is an integral part of their family history. Only minutes from Lake Erie’s shore, the house had initially been Carrie Ann’s great-grandparents’ house, then grandparents, and now it is Janne's.

As a young woman, Janne moved to Windsor to go to hairdressing school, worked as a hairdresser for a while, and then spent many years working as a correctional officer. When Janne’s only daughter Carrie Ann was born, Janne did her best to expose Carrie Ann to their traditional culture. From an early age, Janne brought her daughter to Caldwell Band meetings.

This is a ribbon skirt sewn by Janne. Carrie Ann says her mom has made her at least 16 of these. Carrie Ann wanted to learn how to make them, but she could never sew as fast as Janne.

In 1995, after she had her daughter, Carrie Ann moved to Leamington, where Janne had already returned to live. In 2007 Janne was elected to council at Caldwell First Nation and in 2009 the Caldwell Band office moved to Leamington. Carrie Ann had just finished her accounting degree at college and applied to Caldwell for a finance job. She didn’t get the position, but they offered her a position as a community wellness worker. “It was definitely a win-win!”

(left) Carrie Ann holds a turkey feather fan used for fanning the fire or smudge during ceremony. (right) Carrie Ann’s turtle tattoo with a medicine wheel in its center represents her being from the Turtle Clan. “Hopefully, he is pointing me in the right direction."

Since 2018, Carrie Ann has been working as the Cultural Development Coordinator & Language Champion for Caldwell First Nation. Carrie Ann explains how, when most people think of First Nations communities, they think of reserves. Caldwell has never had a reserve. Connected to this lack of a physical “home base” is that their people are spread out far and wide.

“If Caldwell had had a reserve, like other First Nations, we would not have dispersed, and we would have been a cohesive community. We would have had that knowledge at our fingertips and learned it throughout, but we don’t.”

For this reason, a big part of the programming that Carrie Ann does is about bringing in traditional knowledge keepers to teach their people ceremonies, traditions, and the Anishinaabemowin language. Bringing this knowledge back is central to what Carrie Ann does.

(right) Tobacco ties hang outside Caldwell First Nation headquarters. These are from a pipe ceremony where members put their prayers for what they would like to see happen in their community.

Carrie Ann’s grandfather Isaac II fought in WW2 as part of the Essex Scottish Brigade, who stormed Normandy’s shore. Still, Carrie Ann says he was never allowed to join Leamington’s legion because he was indigenous. In 2009 Caldwell First nation bought the old legion building. “How ironic it is that the legion wouldn’t let my grandpa be a part of it, and now Caldwell First Nation owns the legion building!”

The lake is essential to Carrie Ann, her family, and their community. Both Carrie Ann and her mother Janne share fond memories of smelting off of Pelee Drive. The whole family would go at night time, and if you stood on the dock in smelting season and looked at the shore, all you could see were fires lit by each family.

“The smelt; they really ran. People would leave the beach area with garbage pails full of smelt. You don’t see them anymore. I figure they were all caught. I like eating smelt, but I haven’t been able to do that in a long time.”

The experience of losing the smelt is something they don’t want to have happen with the other species that live in the lake.

“Lake Erie is our lifeline. Without water, we cannot live.”

In her lifetime, Carrie Ann has participated in two sacred water ceremonies.

“The water ceremony is something women do. For us, water is the women’s responsibility.”

In a water ceremony, women stand in the water and use tobacco to sing and pray for the water.

As Carrie Ann explains, copper has a healing energy and can help cleanse the water. For this reason, the “water walkers” (indigenous women who carry an open vessel of water great distances, relay-style as a way to bring awareness to endangered bodies of water) carry the water in a copper pail.

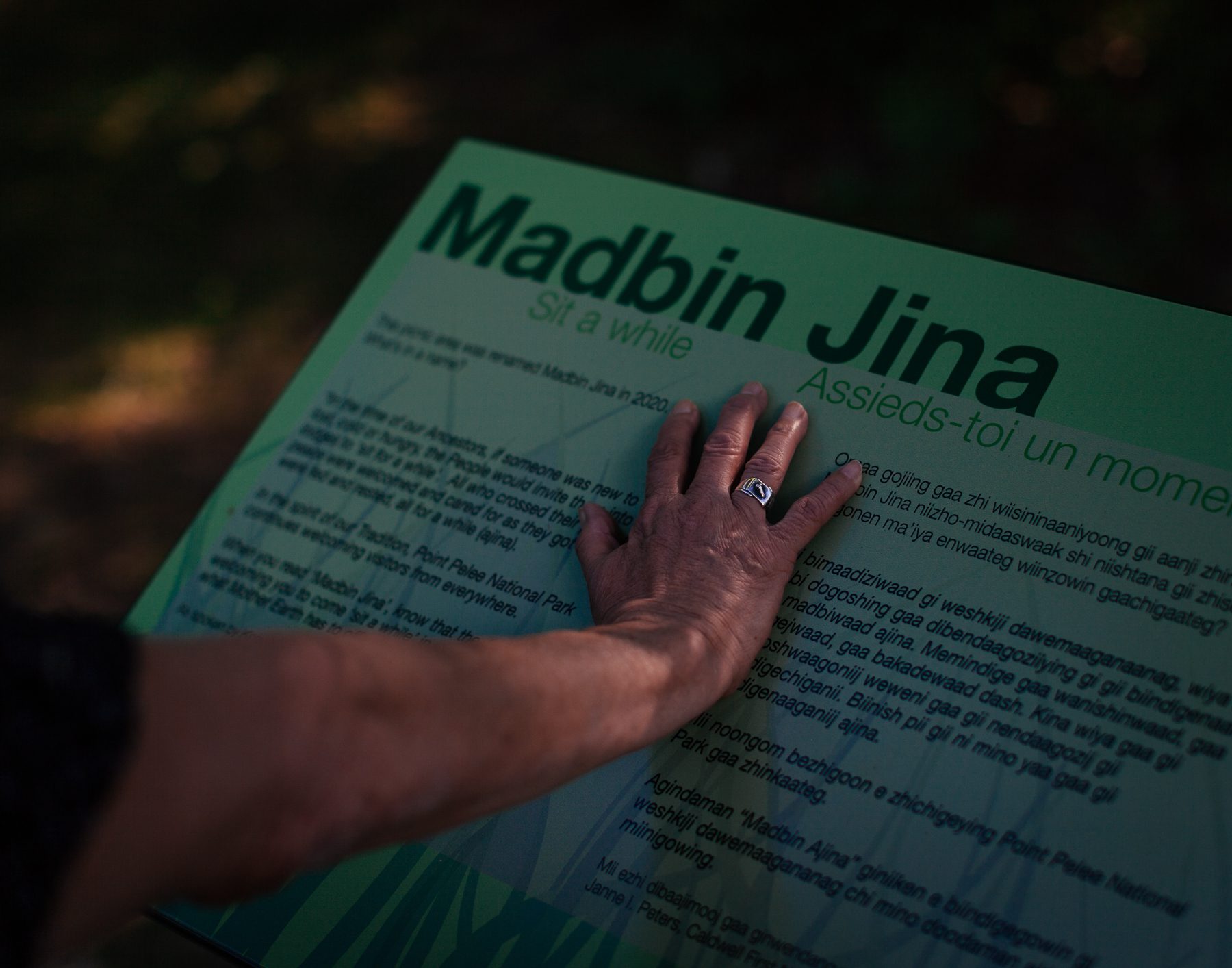

In 2020, Point Pelee National Park's First Nations Advisory Circle decided to rename the picnic area formerly called "Pioneer." The committee chose the name Janne submitted: "Madbin Jina" which means "sit a while".

(top left/right) On the picnic area’s new sign it says: “In the spirit of our tradition, Point Pelee National Park continues welcoming visitors from everywhere. When you read Madbin Jina” know that the Ancestors are welcoming you to come ‘sit a while’.”Janne sits in the picnic area she named Madbin Jina. (bottom) Janne says that every time they have ceremony out at Point Pelee National Park, an eagle flies by.

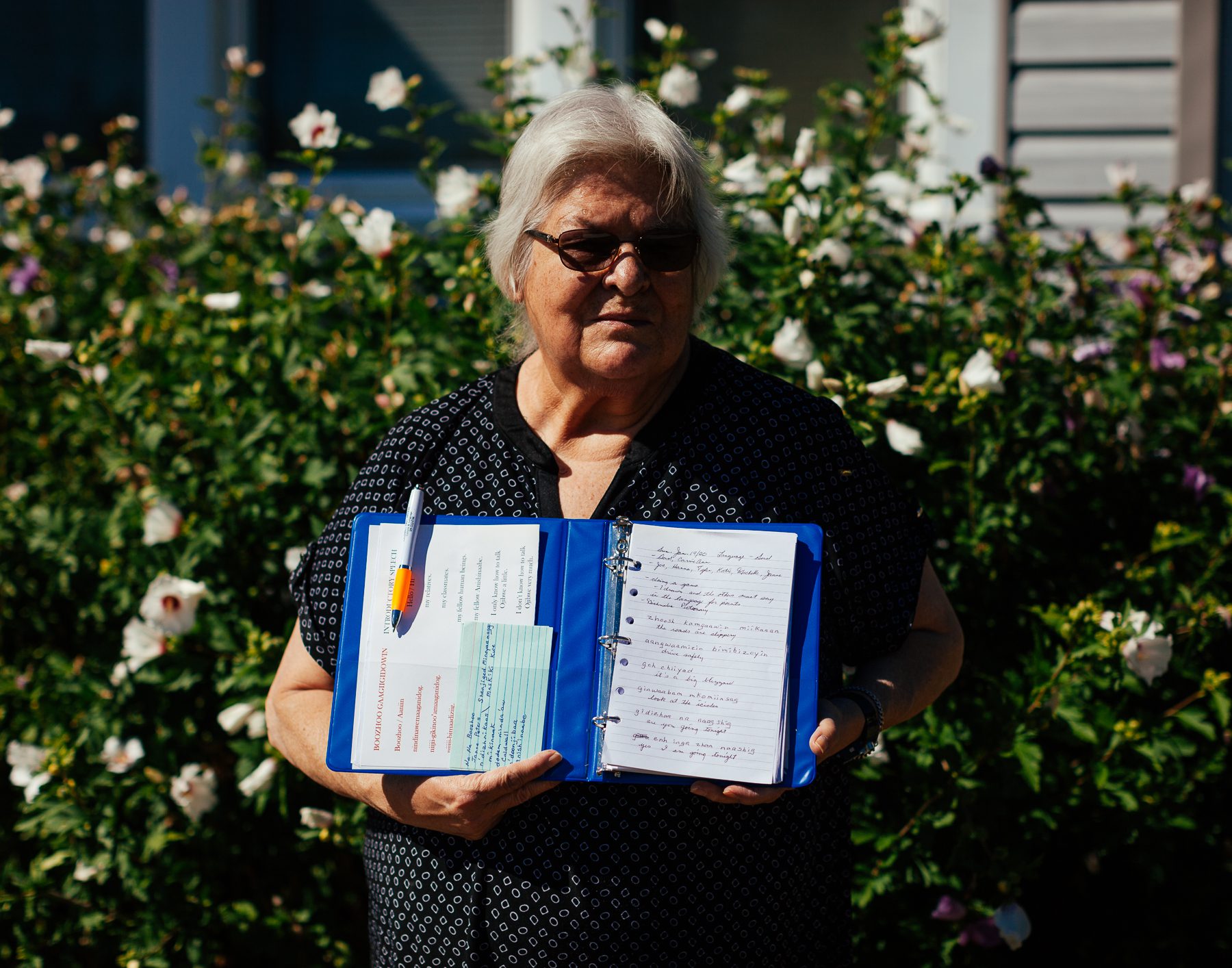

Today, Carrie Ann teaches her mother their language, Anishinaabemowin, a language Carrie Ann says is descriptive and connected to the land. Janne laughs, “I taught her, and now she is teaching me.”

Janne holds her workbook from her studies in Anishinaabemowin, the language that she wasn’t allowed to learn as a child, but her daughter is teaching her now.

Carrie Ann and Janne will continue to visit and have ceremony together in Point Pelee National Park, the center of their people's ancestral territory.

Read More

STORIES FROM THE LAKE

Heidi – Pigeon Bay

Take Action

Lake Erie and the millions of people who rely on it for their drinking water, local jobs, and so much more need your help.

The health of Lake Erie continues to decline. Action is needed more than ever to restore its health for current and future generations.

You can make a difference. Here’s how you can help protect the lake and support the people who are closely connected to it.

EXHIBITION BY: documentary photographer COLIN BOYD SHAFER in collaboration with ENVIRONMENTAL DEFENCE