This is a guest blog by Brendon Samuels

Over the past several years – and especially in the past few months – Premier Doug Ford’s government has made sweeping changes to environmental protection and land use planning rules across Ontario.

The regulations accompanying many recent changes included in Bill 23 have yet to take effect. When they do, the province’s parallel decision to weaken the Ontario Wetland Evaluation System (OWES) will have widespread implications.

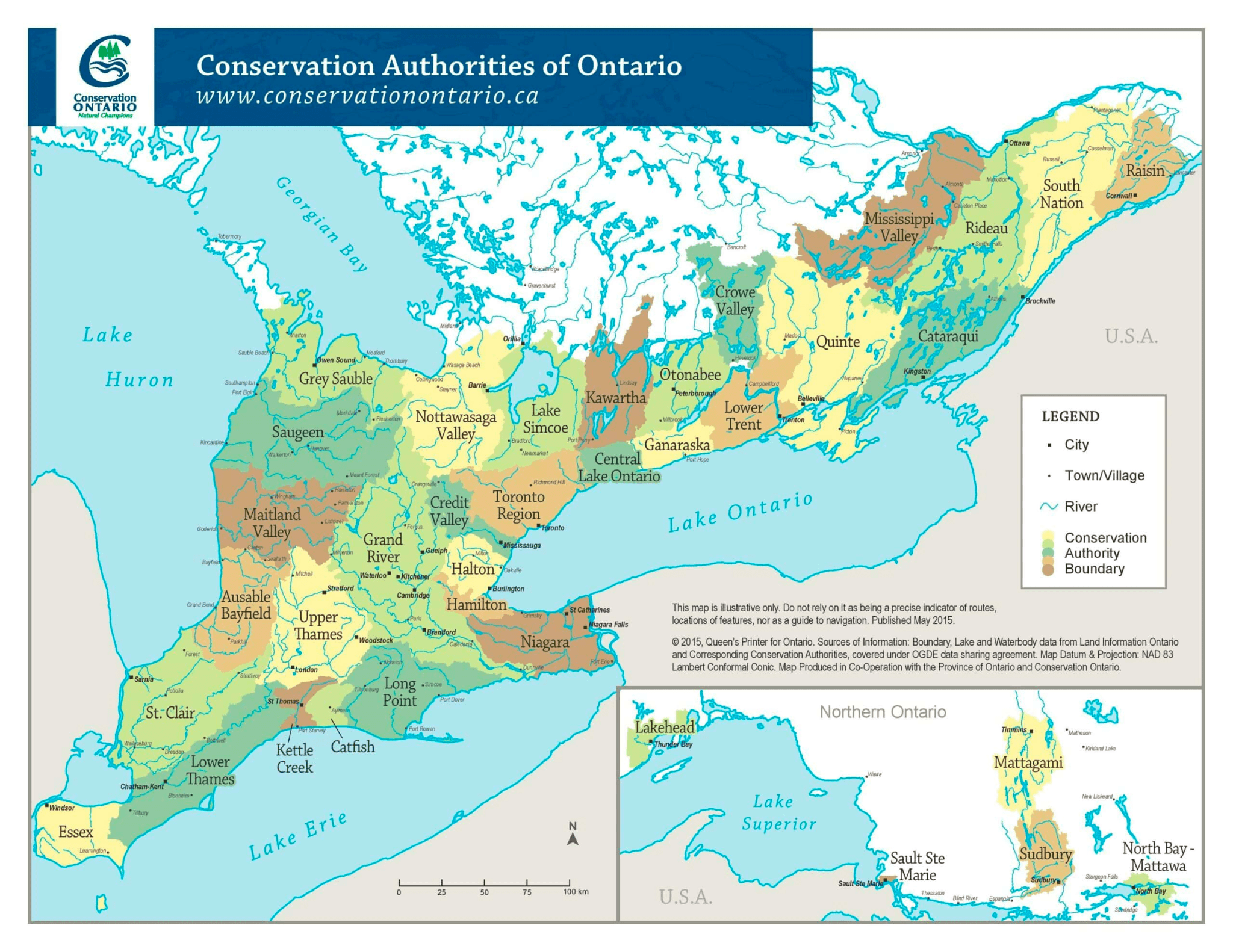

In the weeks since late October, when the province tabled its various proposals, conservation authorities and regional and municipal governments have published reports and statements containing their preliminary evaluation of the effects they are expecting within their jurisdictions. Some of these documents discuss implications for wetlands under the new OWES.

I was curious about the extent of predicted impacts to watersheds and wetlands, so I did some homework. Specifically, I went looking for information about how many wetlands are at risk now that the rules for protecting a wetland as “Provincially Significant” under OWES have fundamentally changed. What follows is a summary of my findings.

Wetlands in Ontario are losing their protection

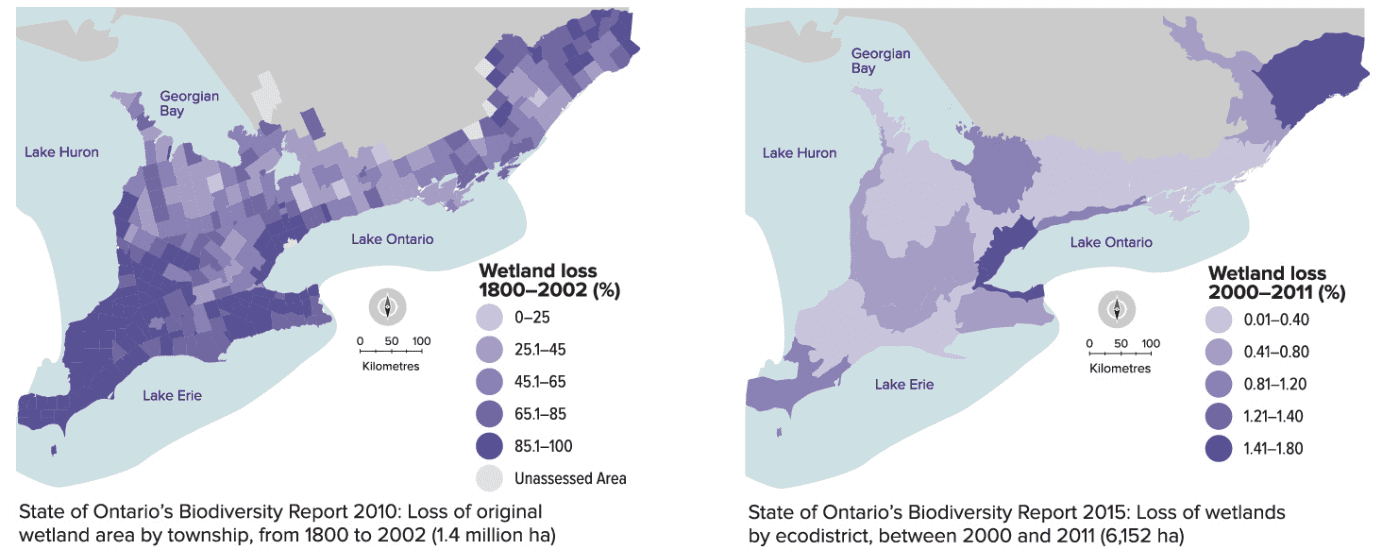

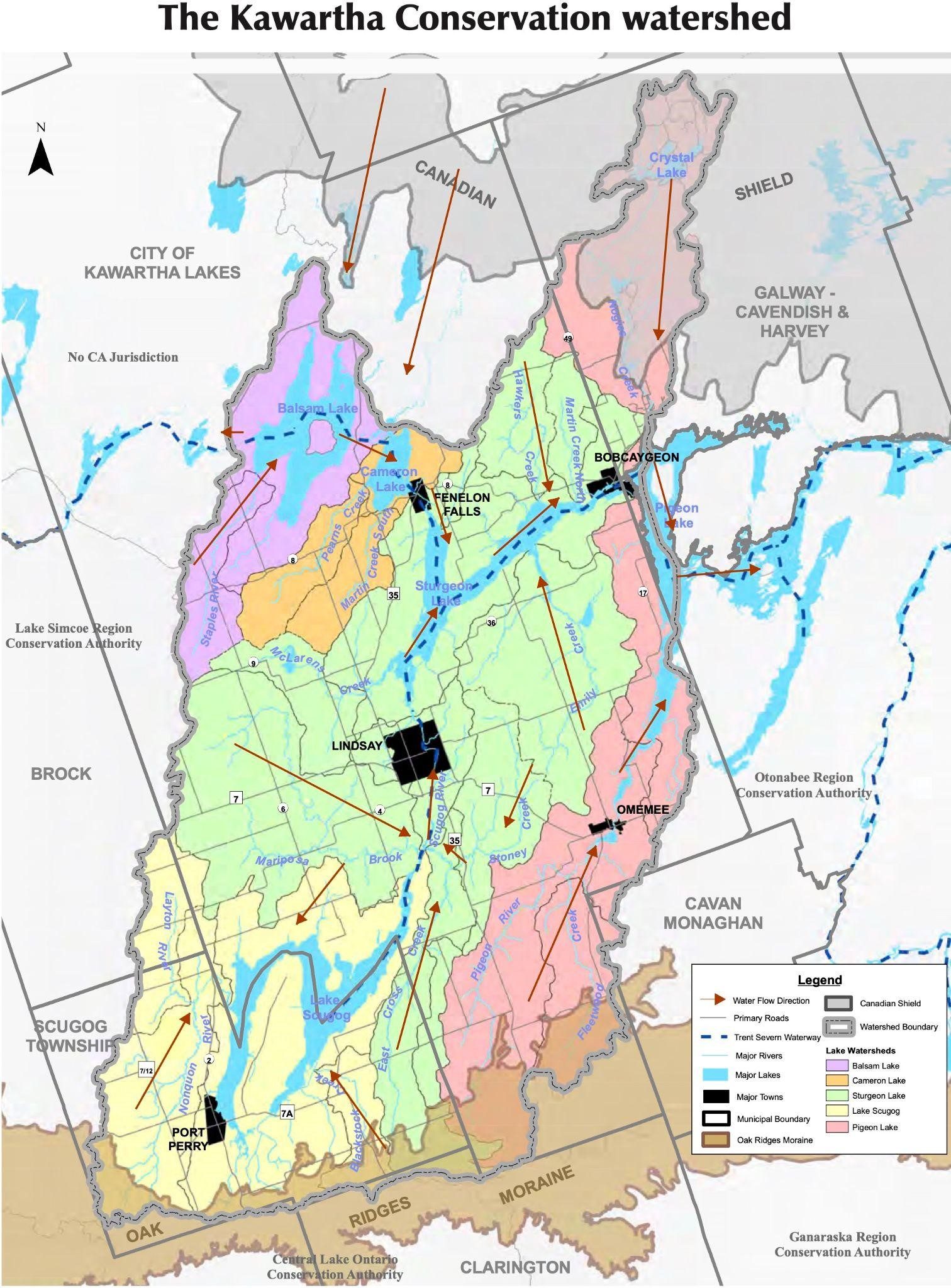

Wetlands in Ontario have declined significantly over the past two centuries, with the most severe losses (over 90 per cent) occurring in southern Ontario. Most wetlands in this area are lost when land is converted for agriculture and urban development. Remaining wetlands are fragmented and damaged by numerous activities, but they are still important and interconnected as part of watersheds. When wetlands are made up of multiple distinct sections separated by small forest or grassland areas, they are referred to by scientists as a “wetland complex.” If evaluators found that smaller wetlands belonged to complexes, they were much more likely to receive protection from development.

Historically, developers or landowners in Ontario had to get permission from their local government, and possibly the provincial government and regional conservation authority, to modify a wetland or build next to it. The degree of protection required depended on how the wetland in question was evaluated under the OWES, which has been used for decades to evaluate the significance of wetlands across the province. Wetlands meeting certain objective, scientific criteria laid out in OWES were given the status of Provincially Significant Wetland (PSW) and were protected from development.

Recent changes to OWES have major implications for how wetlands will be evaluated moving forward, including whether previously evaluated wetlands will continue to receive protection as PSWs. The definition of a PSW has been fundamentally changed because the previous scientific evaluation criteria for wetlands have been reduced or removed entirely. Some of these critical changes include:

- Wetlands smaller than two hectares are no longer being evaluated;

- Smaller wetlands are no longer considered part of a wetland complex and must instead be evaluated on an individual basis. Most components of wetland complexes will not individually meet the criteria to be considered a PSW;

- Presence of habitat for Species at Risk is no longer part of the criteria for PSW status; and

- Historically, wetland evaluations under OWES were administered by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry working in consultation with local authorities. Now, responsibility for OWES is offloaded to municipal governments or private contractors working for developers, most of which do not have resources to employ staff with technical training on the evaluation of wetlands or have a potential conflict of interest because their employers are seeking permission to develop the wetland.

You can learn more about the current evaluation status of wetlands in Ontario using the province’s interactive wetland map tool.

Local and regional authorities predict most wetlands are at risk

Many of Ontario’s municipalities, regional governments and conservation authorities have provided their reactions to the recent changes enacted by the provincial government, which you can find below. These quotes were obtained from various reports, public statements and media interviews published online. Many others are still reacting to recent changes and may not have completed or published their own findings yet.

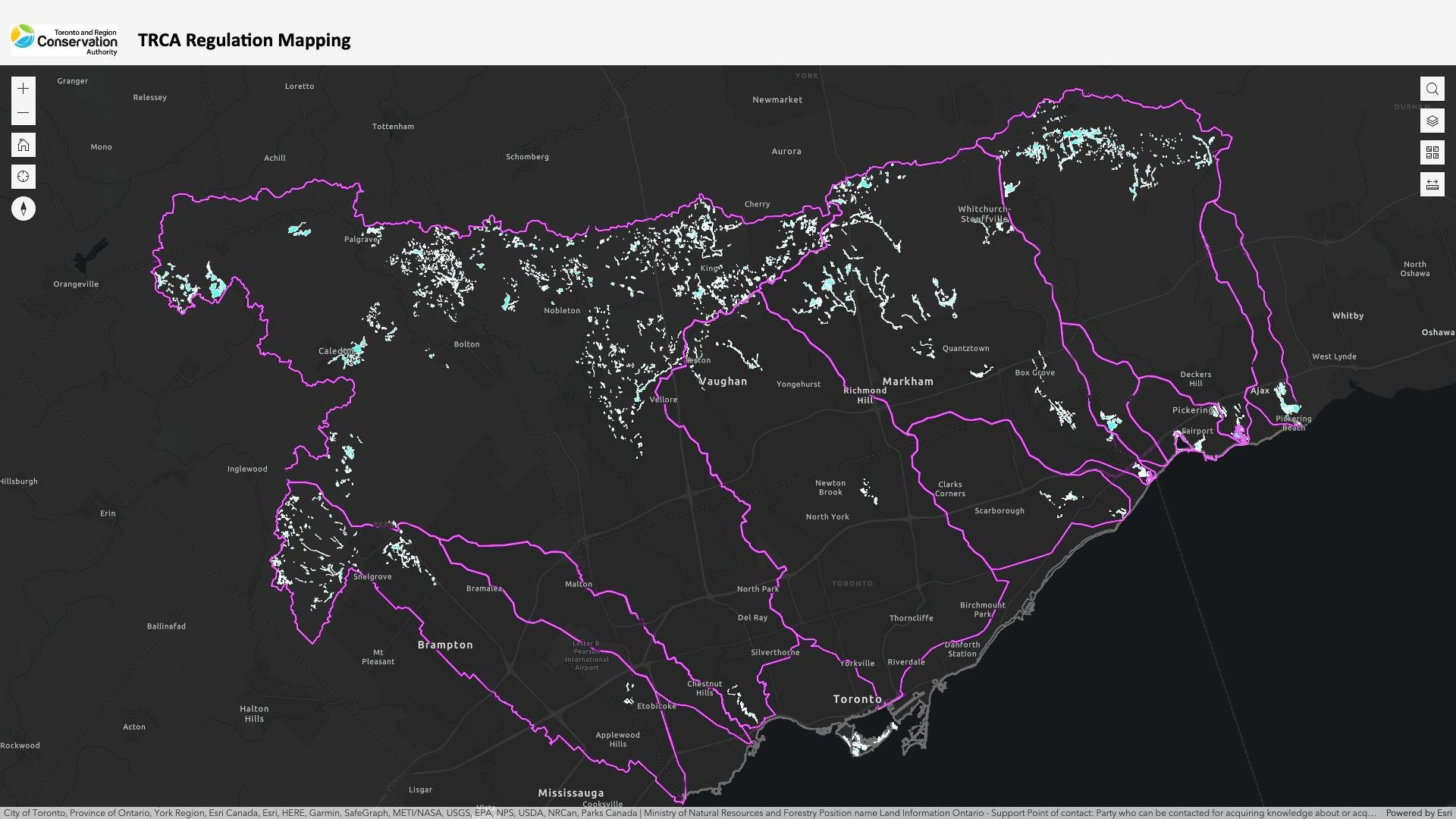

Greater Toronto Area: Toronto Region Conservation Authority serves six municipalities. Their Chief Executive Officer presented a report on Bill 23 on November 10, where he indicated that “The updated OWES manual would maintain that wetlands less than 2 ha need not be evaluated while no longer recognizing the evaluation potential of wetland “complexing”, which accounts for smaller wetlands interconnected by larger hydrologic, social, and ecological functions. It would also expose existing Provincially Significant Wetlands (PSWs) to re-evaluation in isolation. This would significantly reduce the number of PSWs afforded greater environmental protections. Subsequent wetland impacts/removal would diminish their essential natural functions, including flood mitigation, erosion control, conserving and purifying water, supporting biodiversity, and carbon sequestration. The changes contemplated are concerning given that across the Greater Toronto Area, wetlands only cover approximately 1% of surface area and are small (<2 ha in size). Within TRCA’s jurisdiction they are becoming increasingly scarce, particularly in Toronto where around 90% of historic wetlands have been lost.” The Conservation Authority, speaking to The Toronto Star, said, “the numbers are ‘staggering’ and 9,000 of its 10,000 wetlands could be at risk from the proposed changes.”

District of Muskoka: A background report about Bill 23 was presented by senior planning staff to Muskoka District Council (representing six municipalities) on November 14. It states, “District staff have identified that the removal of the wetland complexing process associated with the current OWES means that the connectivity of natural features and their functions will be ignored, including their importance at a relevant scale. Additionally, removal of consideration for Endangered and Threatened species from the OWES assessment process not only ignores the importance of wetlands as key habitats for many of these species in Ontario but increases the likelihood that development may occur in these features that offer invaluable ecosystem services (including flood mitigation, water quality, and carbon sequestration) to Muskoka’s residents.”

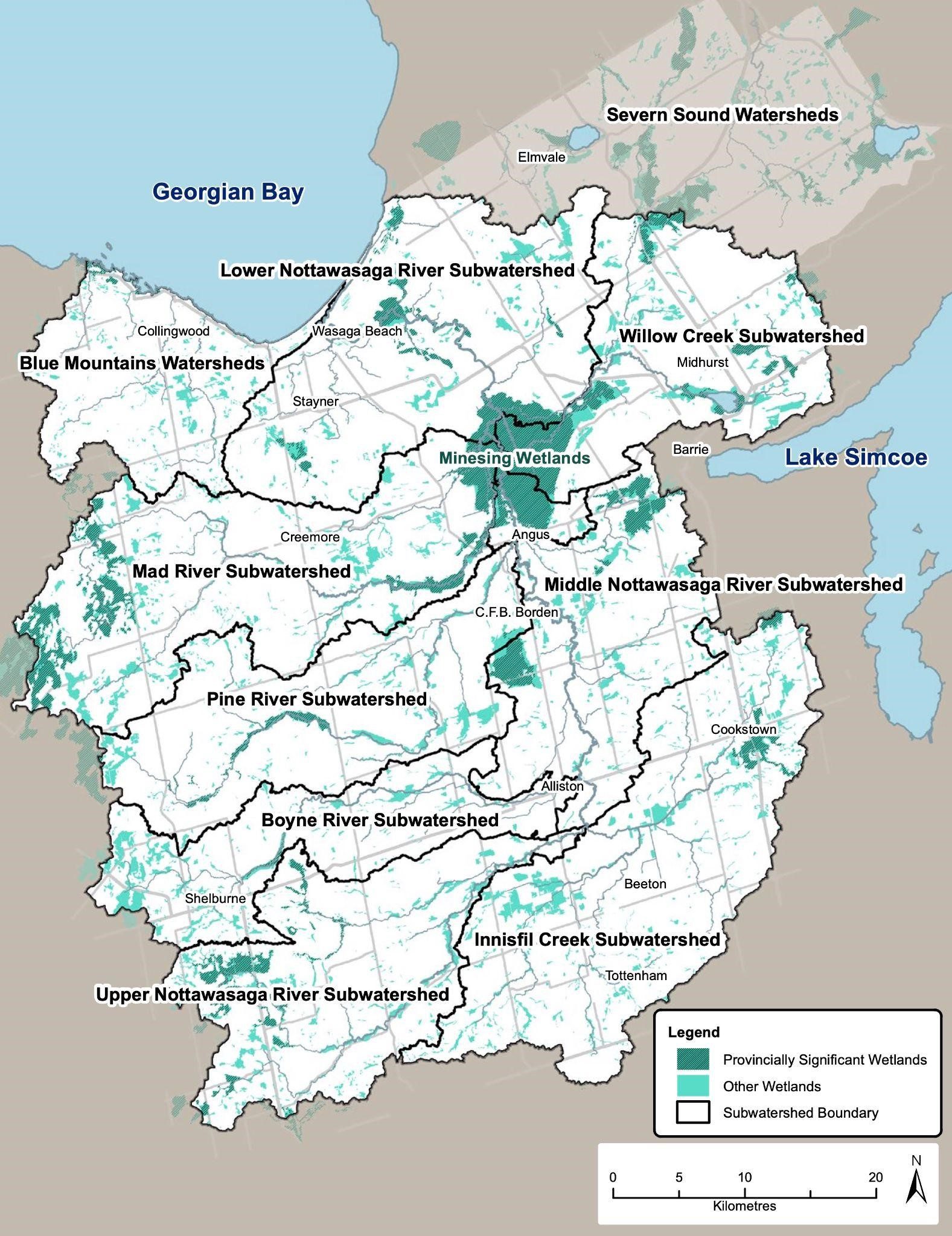

Nottawasaga Valley: The Nottawasaga Valley Conservation Authority (serving 18 municipalities and 3 counties) said in their statement about Bill 23, “Under the current wetland evaluation system, the Nottawasaga Watershed is home to the internationally significant Minesing Wetlands, 33 provincially significant wetlands (PSW), 34 important but non-provincially significant wetlands and several of the unevaluated wetlands that would likely become provincially significant if they were evaluated. If the new legislation is passed, the evaluation score of the Minesing Wetlands will be greatly diminished, and many wetlands, including the Mad River portion of the complex will not meet PSW status.”

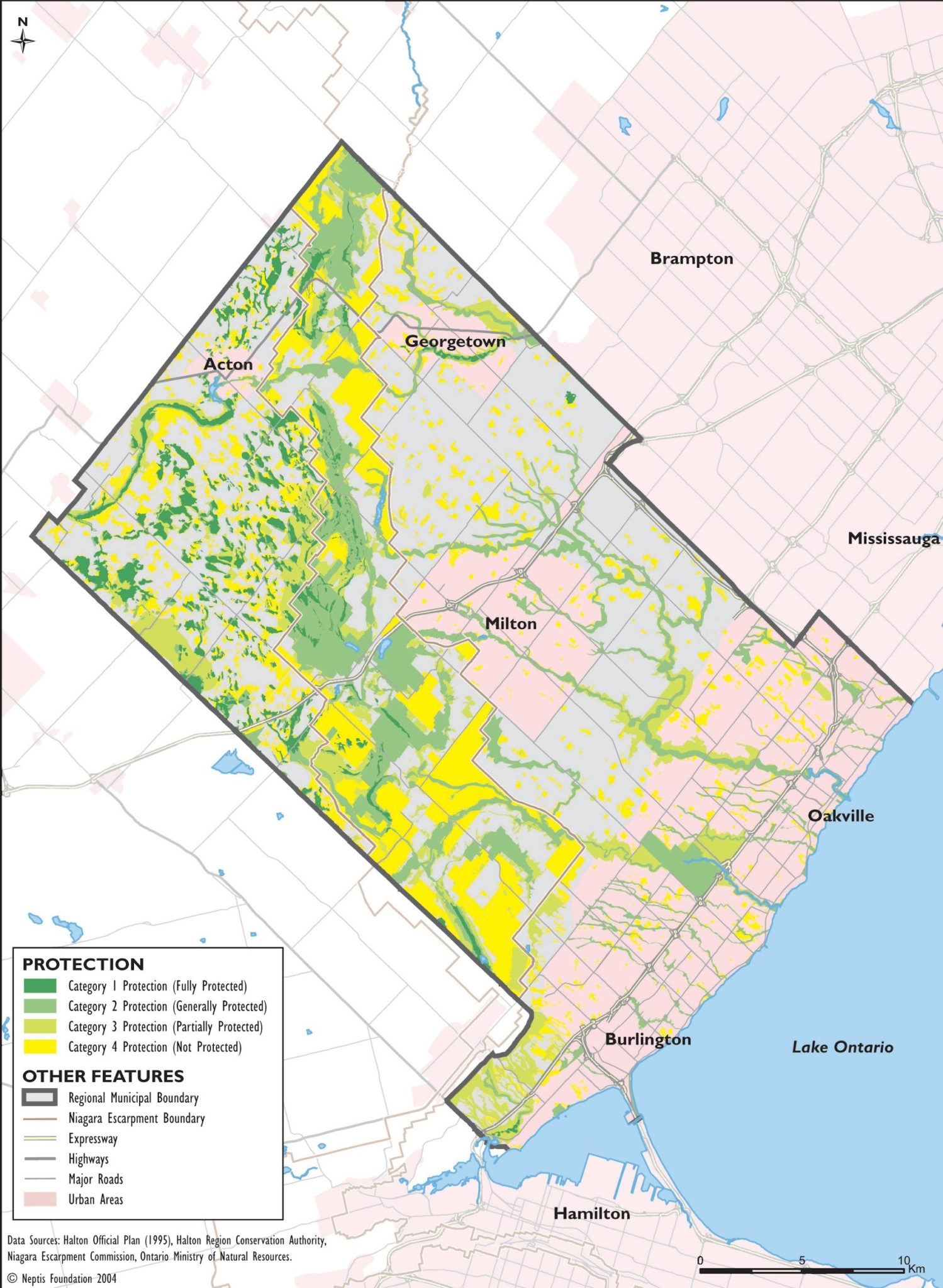

Region of Halton: The Regional Council of Halton (comprised of Burlington, Oakville, Milton, and Halton Hills) received a staff report on November 9 about Bill 23. In their initial comments they stated, “With the proposed changes above, 99% (approximately 6500 hectares) of provincially significant wetlands in Halton Region that are part of ‘wetland complexes’ could be re-evaluated on a standalone basis and determined not to be provincially significant.” In a December 24 article published in The Toronto Star, The Halton Region Conservation Authority is quoted saying: “95 per cent of its Provincially Significant Wetlands could be re-evaluated under the province’s proposed changes.”

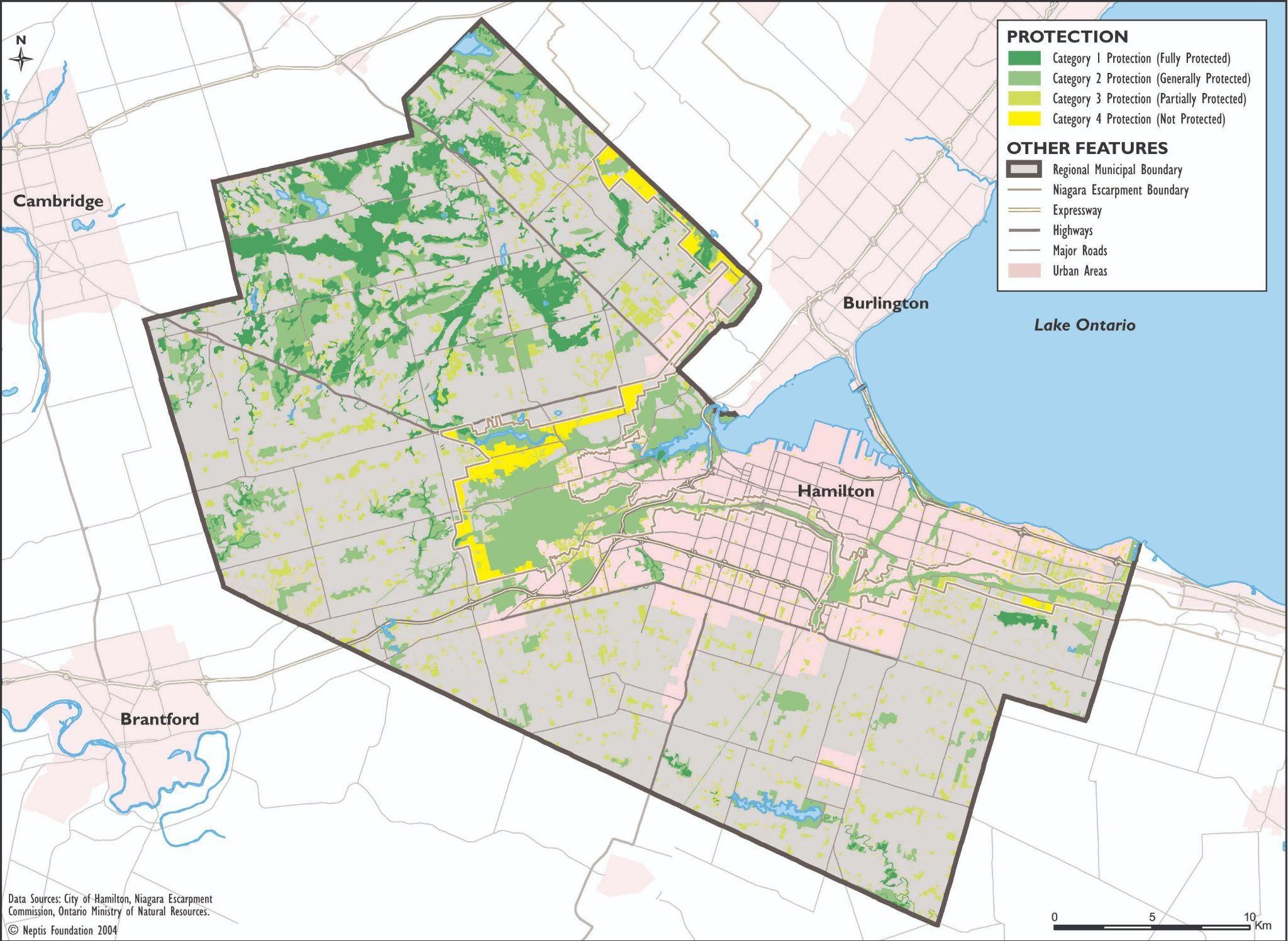

City of Hamilton: The Hamilton Conservation Authority serves the City of Hamilton and Town of Puslinch. Their Deputy Chief Administrative Officer was interviewed in an article published on December 30 by The Hamilton Spectator and said, “Right now, [Provincially Significant Wetland protected status] applies to the ‘vast majority’ of local wetlands — marshy areas covering 8,138 acres — in the watershed overseen by the Hamilton Conservation Authority…But the proposed changes suggest nearly 75 per cent of Hamilton’s provincially significant wetlands could be re-evaluated — and potentially lose default development protection.”

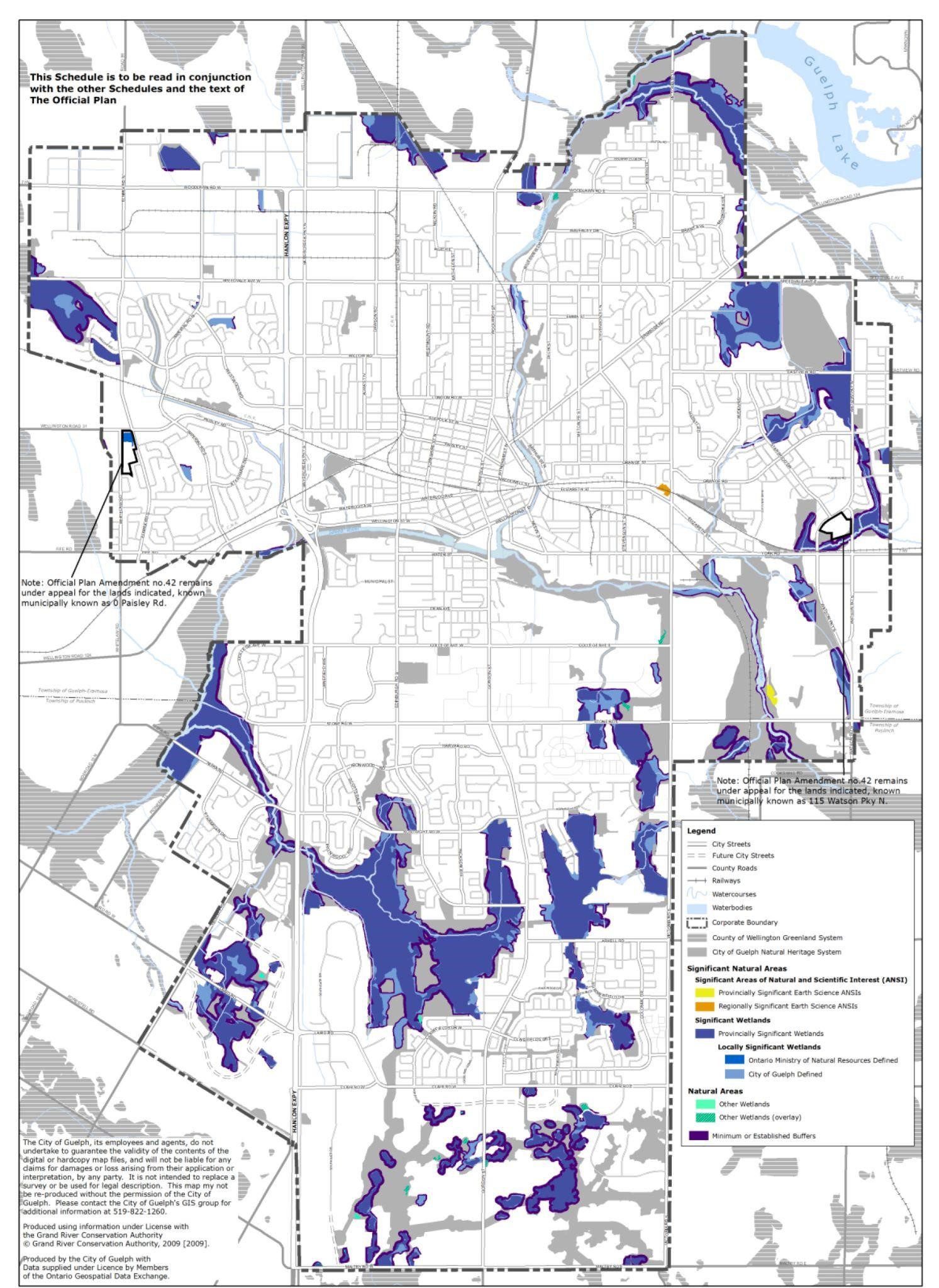

City of Guelph: The Grand River Conservation Authority (serving 32 municipalities) circulated a staff report prepared by the Chief Administrative Officer for the City of Guelph, which stated, “This will likely result in most of the existing Provincially Significant Wetlands (totaling over 600 ha) in Guelph no longer being identified as such. This will lessen the existing protection for the affected wetlands through a reduction in minimum buffers and result in their degradation over time. Further, it appears likely that wetland loss will be realized in the City due to the proposed changes to the OWES (and the proposed changes outlined in ERO number 019-6141 which would eliminate Conservation Authority regulation of wetlands in planning approvals). Initial estimates indicate that up to 48 ha of wetland may lose all protection in the City in planning approvals (i.e., approximately 7% of existing wetland area in the City).”

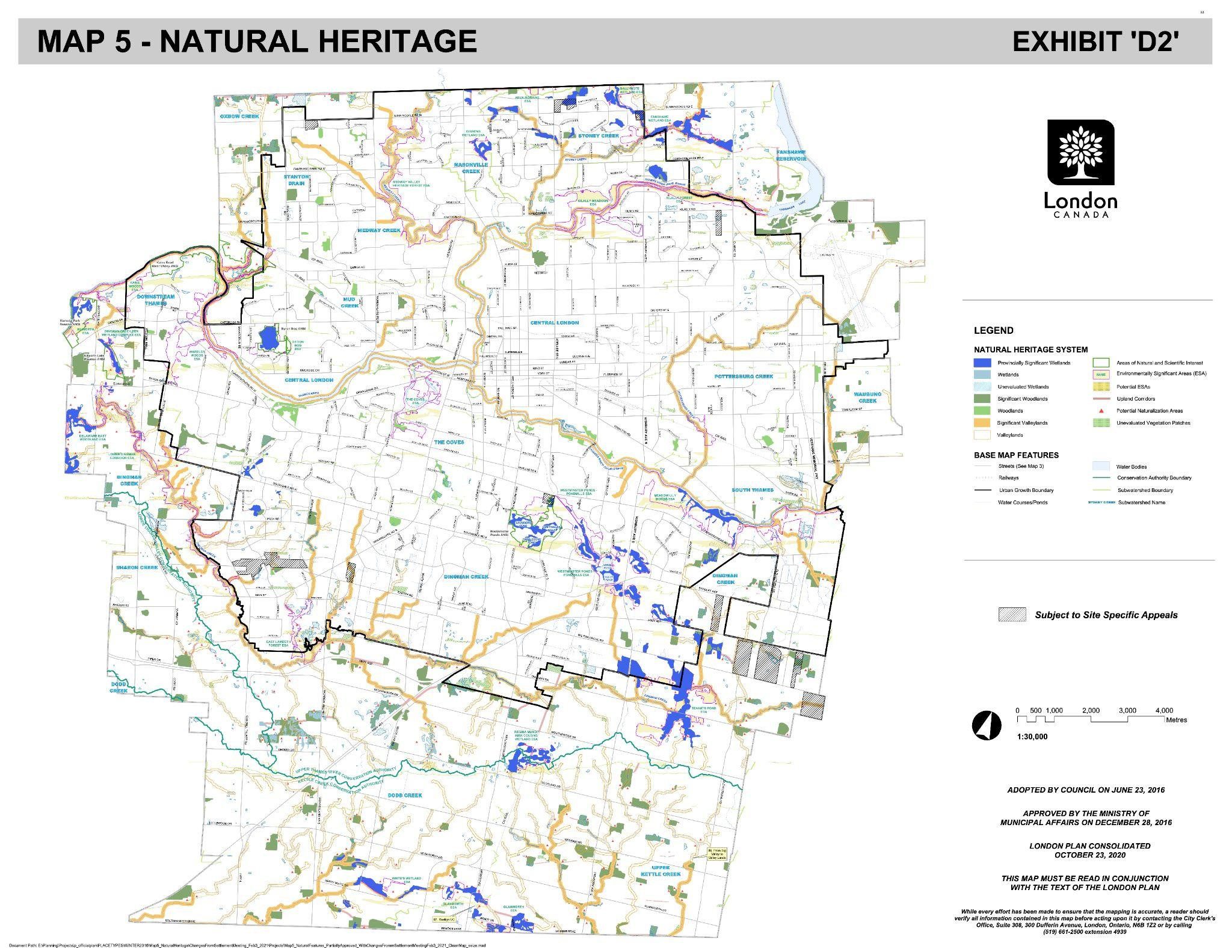

City of London – Oxford County: In a memo about Bill 23 sent to its Board of Directors on November 10, the Upper Thames River Conservation Authority (serving 21 municipalities in southwestern Ontario) describes anticipated impacts to wetlands within its regulated area,“The Upper Thames River watershed currently has approximately 4.6% wetland cover, and only about 1.6% is currently considered Provincially Significant Wetland. With the changes proposed to OWES, the percentage of PSW within our watershed would drop to 1.3% which equates to an approximately 20% reduction in area considered PSW. It should be noted that both the Sifton Bog and the Dingman Creek Fen Wetland Complex would both lose PSW status with the proposed changes, and bog and fen habitats are extremely rare in southern Ontario.”

Niagara Peninsula: The Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority serves the Niagara Region, the City of Hamilton, and Haldimand County. The Hamilton Spectator obtained an internal memo dated October 30 sent to senior Conservation Authority staff warning that“a proposed new wetland evaluation system would result in 70 per cent of ‘provincially significant’ wetlands in [the Niagara Peninsula] watershed losing the status that gives it stronger protection from development. That change alone would contribute to an ‘extremely drastic reduction’ in local wetlands.” The Conservation Authority is mentioned in a December 24 article by The Toronto Star indicating that “biodiverse areas of Niagara could see 80 per cent of identified wetlands ‘negatively impacted.’”

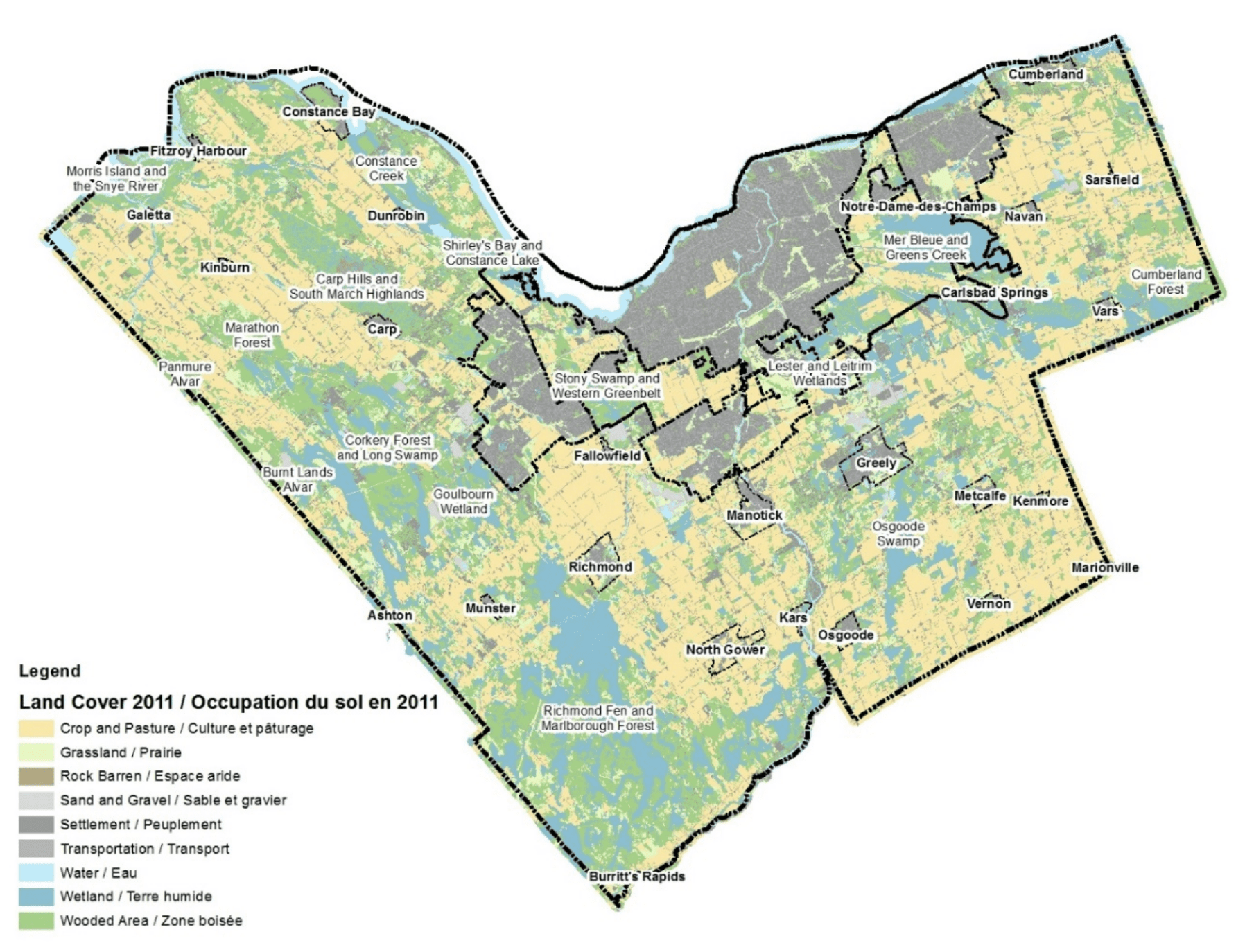

City of Ottawa: The municipal government published a series of staff memos provided to Ottawa City Council on Bill 23 and related projects. The report, dated November 7, states that, “staff do not support the proposed removal of wetland complexing or the inability to reevaluate existing complexes. These changes would expose most of Ottawa’s provincially significant wetlands to potential loss of PSW status and bring complex lands into consideration for urban boundary expansion. Partnered with the described, but not yet outlined, changes to the Provincial Policy Statement, the proposed changes could significantly exacerbate local flooding, erosion issues and biodiversity loss. o For example, this change could bring the Goulbourn Wetland Complex (Stittsville West) back into consideration for urban expansion. Cumulative loss of wetlands will expose the City to increased financial liabilities from flooding and erosion along the Rideau River and other urban watercourses originating in the rural area.”

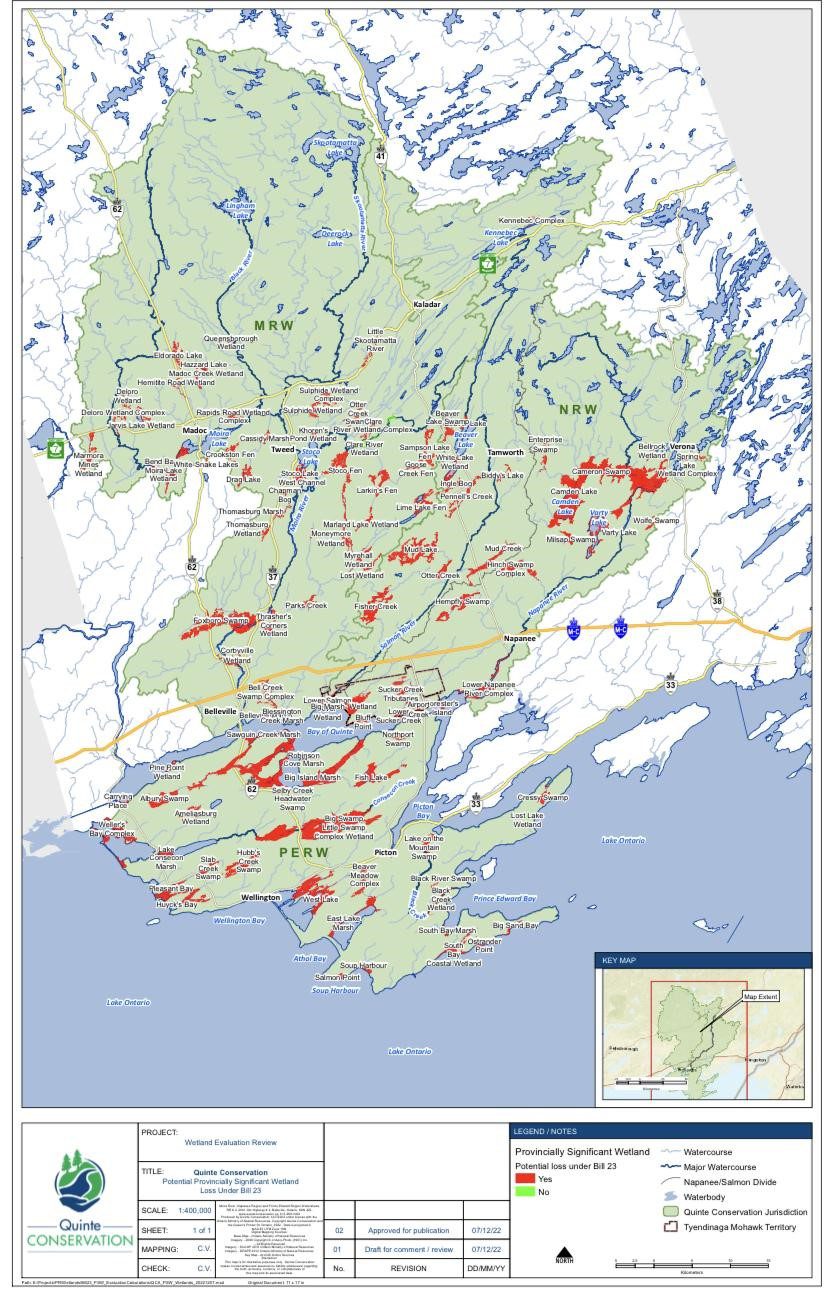

Bay of Quinte: Quinte Conservation Authority (serving 18 municipalities) posted a presentation with an overview of Bill 23 on November 24, with an ominous declaration, “Quinte Conservation’s provincially significant wetlands will be gone”. Councillor Chris Malette from Belleville, Ontario said in a statement, “Under the aegis of Quinte Conservation, we have precisely 100 provincially significant wetlands in the watershed area. Under this new act, 99 of those provincially significant wetlands will vanish. We will have one remaining provincially significant wetland preserved with the protections that go with it.”

What does this mean for you?

Under new provincial laws, wetlands will continue to shrink and be replaced by development at an accelerating pace. As wetlands disappear, so will the many benefits they provide, such as absorbing stormwater, limiting flooding and producing clean water and air. People in Ontario will not experience the full brunt of these changes immediately, but when they do, fixing the damage will be nearly impossible.

Storms are becoming more frequent and severe due to climate change, and the costs of limiting and responding to damage from flooding will continue to rise – at the expense of taxpayers. The average cost to repair a flooded basement is currently over $40,000. Home insurance policies generally do not cover damages associated with flooding, and much of the public is unaware of simple preventative maintenance to safeguard homes from stormwater. Meanwhile, the Auditor General of Ontario warns there is little provincial attention on urban flooding and numerous systemic issues are putting people and properties at risk.

Without Ontario’s wetlands to protect us, we are always just one bad storm away from unmitigated disaster.

Video recorded in early January at the Thames River in London, Ontario. Video courtesy of Brendon Samuels.

Brendon Samuels is a PhD candidate in the Department of Biology at Western University in London, Ontario. He acts as the Sustainability Coordinator for the Society of Graduate Students and the Chair of the City of London Environmental Stewardship and Action Community Advisory Committee. You can find Brendon on Twitter.