On Monday, Ontario released its draft Blue Box regulation. This was a once-in-a-generation opportunity to fix this broken system, but the proposed regulation falls short of what’s needed.

Here’s why this regulation, even though it has some good, is mostly bad and ugly.

The Good: producers will pay for and operate the Blue Box program

The good news is that the proposed regulation would make companies operate and pay for the Blue Box program. This policy approach is called Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and is a step in the right direction. Making producers pay for the trash they put on the market can incentivize companies to design products and packaging that are easier to collect, reuse, and recycle. But for EPR to be effective, the government needs to establish and enforce high, material-specific recycling targets. This regulation doesn’t do that

The Bad: the province is missing out on an opportunity to encourage innovation

High recycling targets are fundamental to good EPR. We want high targets because they keep materials out of the landfill and because they incentivize innovation. If targets are low and relatively easy to achieve, there will be little incentive for producers to innovate.

Innovation could look like:

- Implementing a deposit return program for pop and water bottles and shifting to refillable bottles instead of single-use.

- Changing the kind of plastic resin used in a product, or simplifying the number of layers so the item is easier to turn into a new plastic item.

- Moving away from single-use products entirely, and providing consumers with products in refillable or reusable containers made from glass and metal (which can be recycled many more times than plastic).

Unfortunately, the province’s proposed targets — especially for plastics — are too low to encourage any of these solutions.

The Ugly: Producers only have to recycle 40 per cent of the most problematic plastics

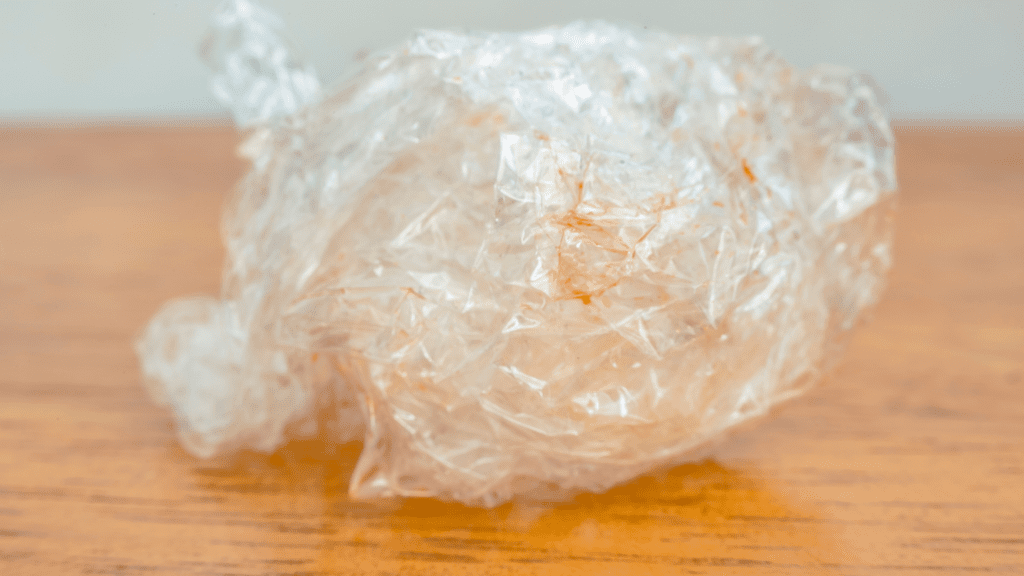

The proposed recycling targets are abysmal. The target for rigid plastic (shampoo bottles, berry containers, juice jugs) is 60 per cent. For flexible plastic (bags, pouches, wraps, etc.), it is 40 per cent. That means that producers can meet the requirements of the regulation if the majority of their products and packaging are piled in landfills or the environment, or worse yet, burned in incinerators.

Producers could argue that these targets are realistic given how challenging some of these products and materials are to recycle. But that’s kind of the point! If a product or package is so hard to collect and recycle that the absolute best-case scenario is 40-60 per cent of it polluting the planet, it’s time to phase these materials out entirely. Bye Felicia!

The Ugly II: Producers can ignore hard-to-recycle materials like styrofoam

The province has proposed targets for broad material categories: rigid plastic and flexible plastic. This is a problem because lots of hard-to-recycle plastics can hide in those broad categories, and as a result, will still end up in landfills.

For example, styrofoam cups and takeout containers would fall into the ‘rigid plastics’ category along with shampoo and laundry detergent bottles. But shampoo and laundry detergent bottles are made from a kind of plastic that is heavier and easier to recycle. So every shampoo bottle gets producers closer to their target faster. And because the targets are so low (see above) producers are unlikely to meaningfully address these problematic products like styrofoam.

The province can and should do better when it comes to single-use plastic and packaging waste

The province needs to improve the targets in the proposed regulation—not just shift the costs of the existing, stalled Blue Box program to producers. And that’s one of the things we’ll be telling the Minister during the 45-day public consultation on the draft regulation.

We’ll also be calling on you, our supporters, to urge the province to get this regulation right, and keep single-use products and packaging out of landfills and incinerators. Stay tuned.