This is a guest blog by Rebecca Jane Houston. Rebecca is a settler sculptor and installation artist from Toronto. She works with found and reclaimed materials to create interactive installations that urge an encounter between the audience and the matter of the sculpture itself. Houston is a graduate of York University and a member of the Akin Collective.

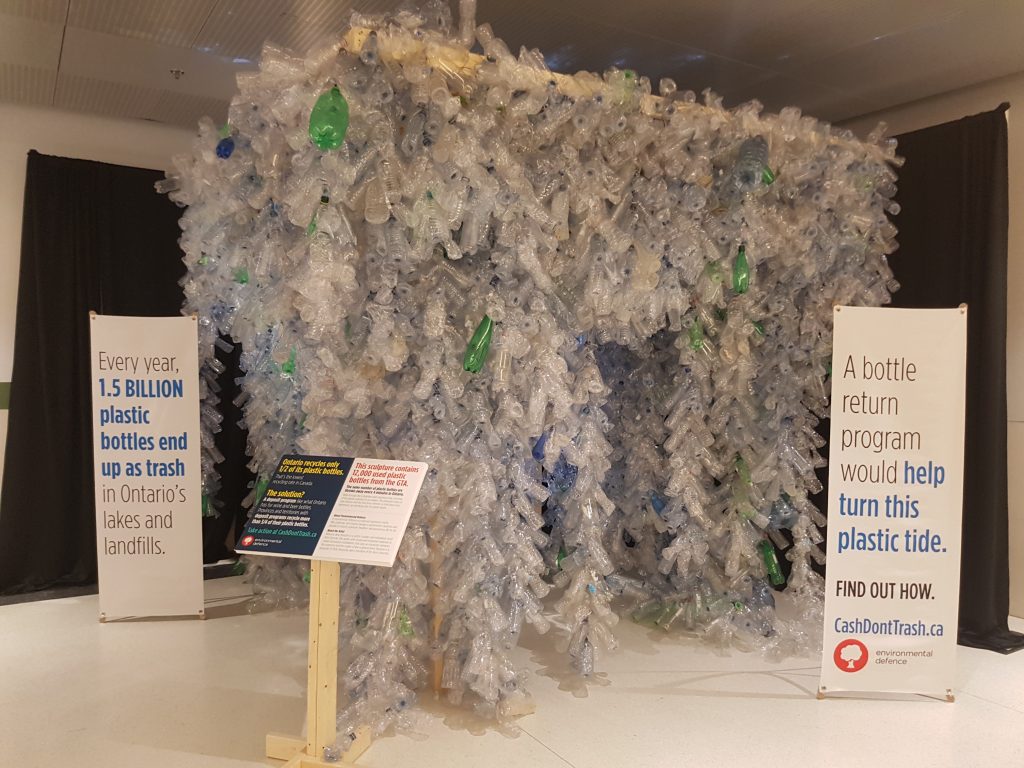

Rebecca recently designed and built an interactive art installation made of 12,000 used plastic bottles. This sculpture was part of Environmental Defence’s Cash it! Don’t trash it campaign calling for an Ontario deposit return program for plastic bottles. The installation was displayed February 15 at Union Station.

Last December, I was approached by Environmental Defence to build a sculpture out of 12,000 used plastic bottles to be displayed at Union Station in Toronto. Little did I know how much this project would personally impact me.

When I started the project, I was overwhelmed by the number of bottles that were delivered to my temporary studio in Trinity Square in Toronto. Twelve thousand is just a number until you are physically surrounded by the piles of bags of dirty plastic. That was the starting point of understanding what it might mean to bring others into an experience of being surrounded by the waste — even for a moment. But for me, the experience went on for six weeks.

The process of turning plastic into art

The project had some challenging moments. One concern I had was if I was making the bottles too beautiful. I debated whether or not to remove the labels. By removing them, I wouldn’t advertise any brands. However, if I left the labels on, it would hold the corporations who make the bottles accountable. My final decision was to remove them, so that the light projecting the waters of the Don River would shine through the bottles.

That is part of the complexity. Plastic is pretty when it’s shiny and the intention of that prettiness is to seduce us. We are meant to feel safe, clean and modern when we hold a single-use bottle. But the truth of the toxicity of the plastic is revealed when it becomes dirty, degraded and broken down. People who walked through the installation had a complicated set of reactions. Most expressed this feeling that they were simultaneously attracted to the light of the moving river as it shined through the bottles, while at the same time they felt disgusted by the sheer number of bottles they were surrounded by.

The impacts of this project

On a personal note, the creation of this installation really gave me a deeper sense of the scale of the problem of plastic pollution in Ontario. Before, I took our recycling system for granted, but now I see things differently. Our lakes and oceans really are absorbing the impact of our poor decisions. The problem has also become much more local in my mind. I only thought about plastic waste floating in our oceans, but didn’t realize how much plastic was right here at home in the Great Lakes.

Hopefully, for the people who interacted with the thousands of plastic bottles in the installation– some covered in dirt or with bits of garbage inside them–they also saw that drinking from one is not an insignificant decision. Because each time you purchase a single-use bottle, you are just adding to this pile.