From Dumb Growth to Smart Growth

In the 1950s, when the car was king, far-flung auto-dependent communities sprang up across the Greater Golden Horseshoe region. We’ve learned a lot since then. We know now that old style sprawl left us with huge municipal, infrastructure and personal debts, degraded our health, and paved over some of our best farmland and forests.

(Adobe Reader is required to read this pdf report. Please ensure you have the latest version.)

In the 1950s, when the car was king, far-flung auto-dependent communities sprang up across the Greater Golden Horseshoe region. Today we know that old-style sprawl left us with huge municipal, infrastructure and personal debts, degraded our health, and paved over some of our best farmland and forests. Some want to keep this outdated model. But many leaders in our communities know that if we don’t change our approach to growth, we risk our health, economy and climate.

It’s time cities in the Greater Golden Horseshoe region grow up, not out. Ontario’s Greenbelt Plan and the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe are award-winning steps in the right direction. The plans work together to protect our farmland and forests while encouraging smarter, more efficient cities and towns. With improvements, they can guide us to a better future. They can help us build walkable, transit-friendly communities that are better for our environment, health, and wallets.

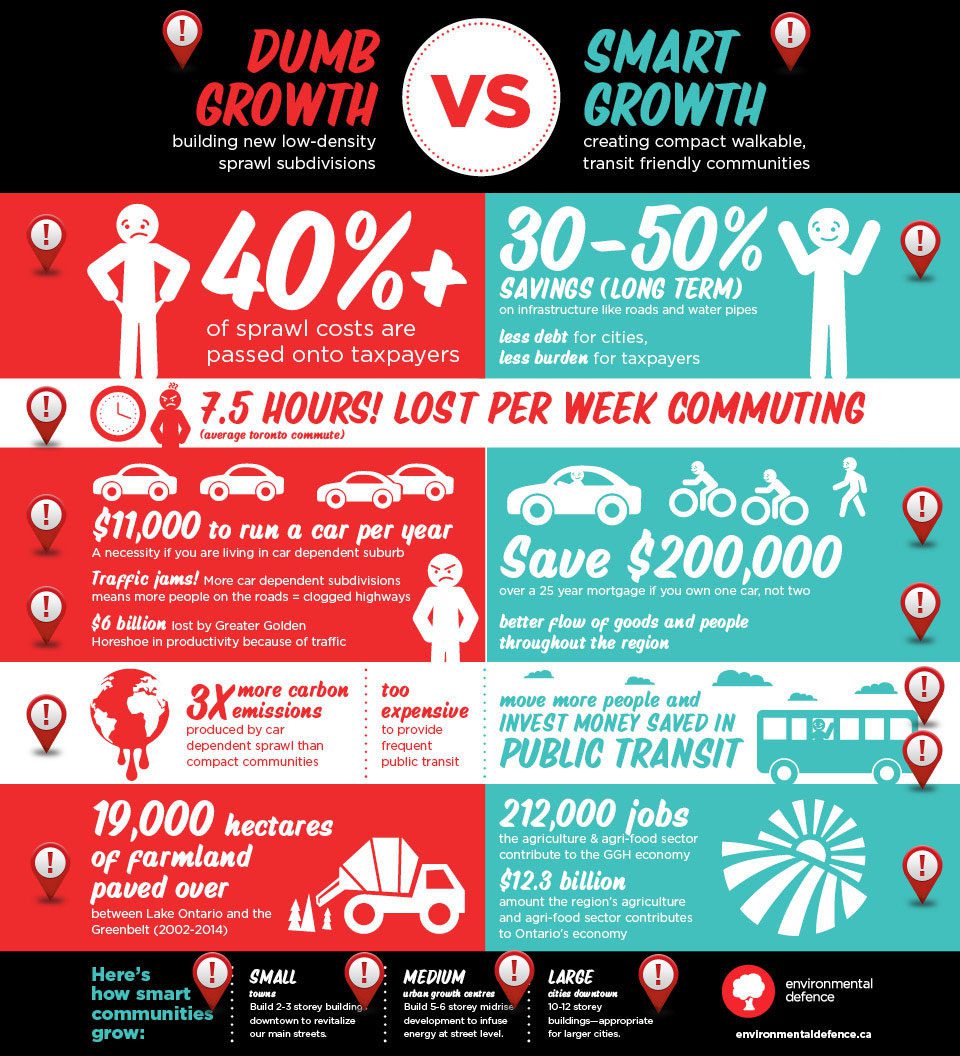

Some of the priciest services that communities need are those residents don’t see, such as underground pipes that provide water and sewers to our homes. In a low-density development, it is expensive to provide these services and they generally require debt financing. This can be a burden on municipalities’ finances since development charges rarely cover the full costs of providing these services. And municipalities pass these higher costs along to existing residents in the form of taxes.

In contrast to a sprawl development, in an existing urban area many services (such as roads, underground pipes, schools and parks) are already available so it’s less expensive to provide them to efficient developments. This can free up more funds for municipalities to invest in other needed services like public transit and community spaces. In an efficient, compact community residents aren’t on the hook for subsidizing sprawl to the same extent as in a low-density town or city.

Being stuck in traffic daily is frustrating. Not surprisingly, these days many people don’t want to live in a car-dependent subdivision. In a recent survey of homeowners, RBC and Pembina found that homebuyers prefer walkable, transit-friendly communities. For the same reason, employers are choosing to relocate to urban centres, rather than corporate office parks. Employees – especially younger employees – want to be able to walk or take transit to work. And some baby boomers are choosing to relocate to more compact communities, where they don’t need to drive daily. Whether younger or older, a car-dependent lifestyle is no longer the preferred option for many.

Commuting by car can have big financial costs. A 2015 TD Economics report identified that most 905-area households rely on cars for their commute and this impacts household finances. Car ownership is a significant factor in household debt levels. In addition to the financial costs, studies have shown living in sprawl communities can impact people’s health because there is less daily opportunity for casual exercise.

The Toronto Board of Trade estimates traffic congestion costs our economy $6 billion a year, rising to $15 billion a year by 2031 if we don’t make significant investments in commuter services. If we want to foster mobility across the region, we need to stop putting the car — and roads and highways — at the front end of our city planning. And we need to stop encouraging car-dependent sprawl developments that put more people on the roads.

Building smarter – more intensive and efficiently – makes it more feasible to provide public transit, which means more people aren’t stuck in cars. It also means more people can live closer to where they study or work. By giving up one car, a family living in an urbanized area can save $200,000 over 25 years. Living in a walkable, compact community promotes a healthier lifestyle where people walk rather than drive for daily chores like grocery shopping or commuting to work or school.

If we build more efficient communities and invest in public transit, it would mean fewer people clogging our highways. Reducing congestion would improve regional economic development. Businesses could get their goods to market quickly and at a lower cost than spending hours stuck in traffic.

When millions of people live in car-dependent suburbs, many with two cars per house, vehicles clog our highways and contribute to global warming. Car-dependent development typically produces about three times the emissions of efficient, walkable, transit-friendly communities.

Smarter growth is better for our climate and makes it more financially feasible to invest in rapid regional transit and bike lanes that get more people out of their cars. Providing more options to move people across the region to homes, jobs and schools is better for our climate. Let’s plan our growth around our existing transit services, and invest in making those transit services quicker to get more people moving across the region quicker.

Building smarter – more efficiently – means we don’t need to pave over farmland and forests. Ontario’s Greenbelt is a natural carbon sink and filters our water. Over the last 10 years, the Greenbelt’s forests and nature areas have offset the pollution equivalent of 255 million cars. Preserving and strengthening the Greenbelt is better for our shared climate and clean water sources.

In the last decade, we’ve lost 18,978 hectares of the best farmland (Class 1 and Class 2) between Lake Ontario and the Greenbelt. Without the Greenbelt, we would have lost an estimated quarter million acres of fertile farmland by 2031 to sprawl development. Despite having a provincial plan to curb urban sprawl, most municipalities continue to build 60 per cent or more of new development on greenfields rather than in existing urban areas. When we pave over agricultural land, it hurts our economy and our environment.

Farmland is essential to our economy. In Ontario, the agri-food sector is the largest economic sector, responsible for 212,000 jobs in the Greater Golden Horseshoe. Ontario is the largest food and beverage processing jurisdiction in Canada and among the three largest in North America. It’s time to find a smarter model of growth than paving over productive farmland.

Smarter growth doesn’t mean an influx of high-rise condos. The Growth Plan identifies urban growth centres and the targets assigned to these vary depending on the community’s size.

In smaller urban growth centres, the density target is 150 people and jobs per hectare or 60 persons per acre. This applies in the downtowns of Barrie, Brantford, Cambridge, Guelph, Peterborough, and St. Catharines. This density is consistent with existing Main Street buildings in these towns, which usually have two to three storey buildings, with commercial uses on the ground floor and residential or office uses above. By redeveloping under-used building sites, with infill, and creatively reusing heritage buildings we can create new neighbourhoods within our existing urban areas and bring new life to our downtowns.

Even in larger communities, smart growth still doesn’t mean an influx of 50-storey condos. The following cities are designated as urban growth centres: Brampton, Burlington, Hamilton, Kitchener, Uptown Waterloo, Markham, Downtown Milton, Mississauga City Centre, Newmarket Centre, Midtown Oakville, Downtown Oshawa, Downtown Pickering, Richmond Hill/Langstaff Gateway, Vaughan Corporate Centre. For urban growth centres, the density target is 200 people and jobs per hectare or 80 per acre. Depending on the layout of the building, this target is consistent with 5-6 storey mid-rise developments – the kind of developments that are friendly to pedestrians, still allow for plenty of sunlight and can infuse a block with vitality when a mix of stores and restaurants are at street level. This scale of development provides the density needed to provide regular all day public transit services.

In larger cities, the Growth Plan does provide direction for higher density. But that’s in places where the scale is appropriate. In city centres — downtown Toronto, Etobicoke, North York, Scarborough — the target is 400 people and jobs per hectare or 161 per acre. Depending on layout of the building, this target is consistent with a 10 to 12 storey building, which isn’t out of place in a city centre.