50 Years of Sprawling Tailings

Mapping decades of destruction by oil sands tailings

The oil sands region lies in northern Alberta, where decades of mining in the oil sands has left a pervasive legacy of harm to the environment and people.

The environmental impact of the oil sands is clear by the harmful effects caused by their wastewater, disposed of in pits known as tailings “ponds.”

These massive human-made bodies of sand and fluids hold the toxic waste from the oil extraction process. And despite the small scale implied by their name, tailings “ponds” stretch as far as the eye can see - impacting healthy boreal systems, sprawling through Indigenous territories, leaking contaminants into groundwater and emitting greenhouse gasses.

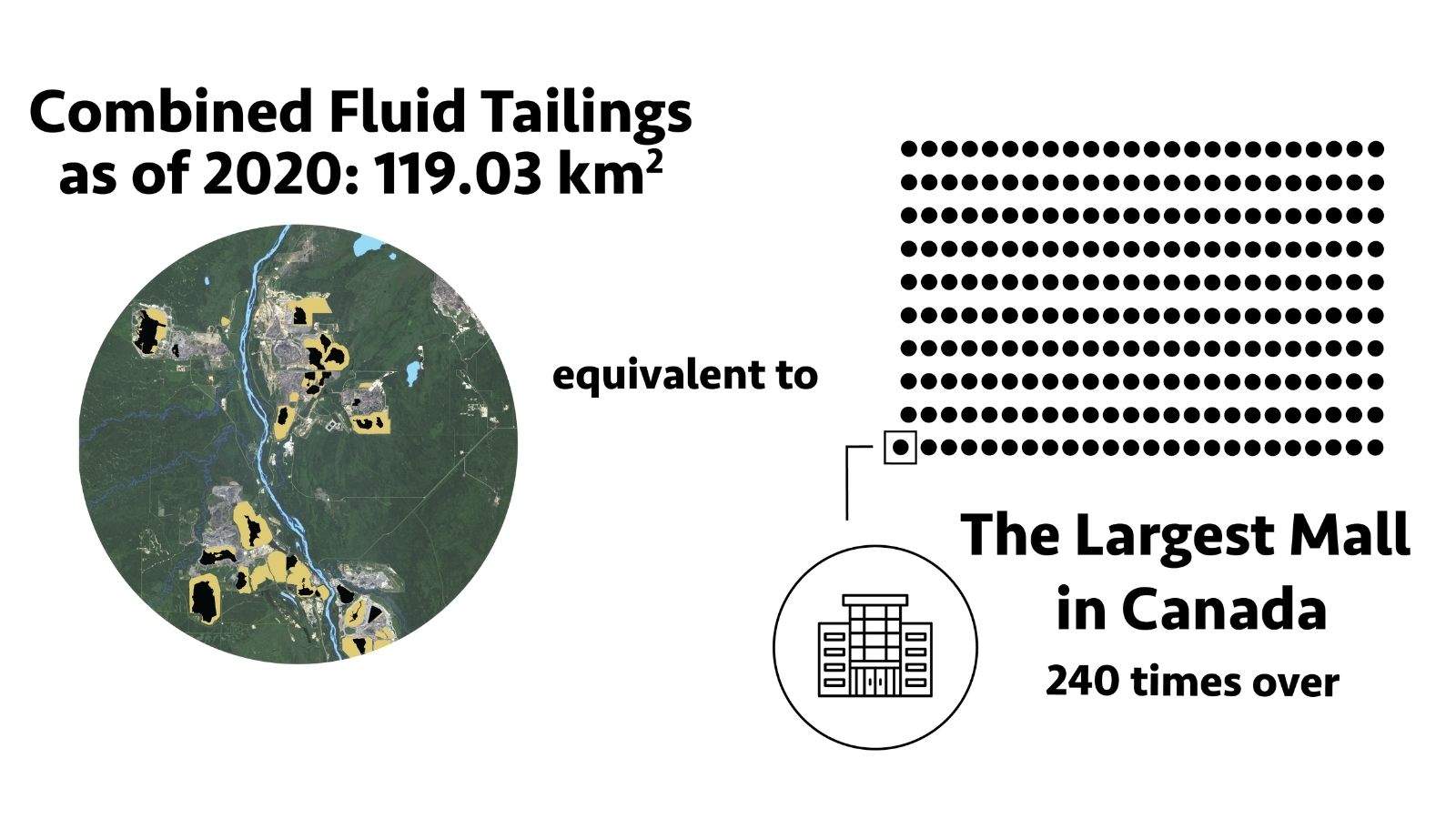

The risks associated with the large volume of oil sands fluid tailings have been growing for decades. In this report, they are referred to as tailings “ponds” for consistency with the term used by government and industry despite the fact that the volume of these human-made basins far surpasses what should be called a true pond. Since the first oil sands project in 1967, the increase in the number and size of tailings “ponds” has been momentous.

As of 2020, there are 30 active tailings “ponds” across nine oil sands projects covering over 300 km of the boreal forest. All the tailings “ponds” are located dangerously close to the Athabasca River - one of Canada’s major rivers that flows through Alberta and the Northwest Territories to eventually join the MacKenzie River, which empties into the Arctic Ocean.

The tailings maps produced in this report are all based on publicly available and open-source data. While these mapping products may already exist for industry and government, it can be challenging for the public to access these types of maps freely. Our report’s maps were created to show the public how large tailings “ponds” have become and provide downstream communities with the tools to defend and protect their waters, at a time when the risk posed by tailings is growing.

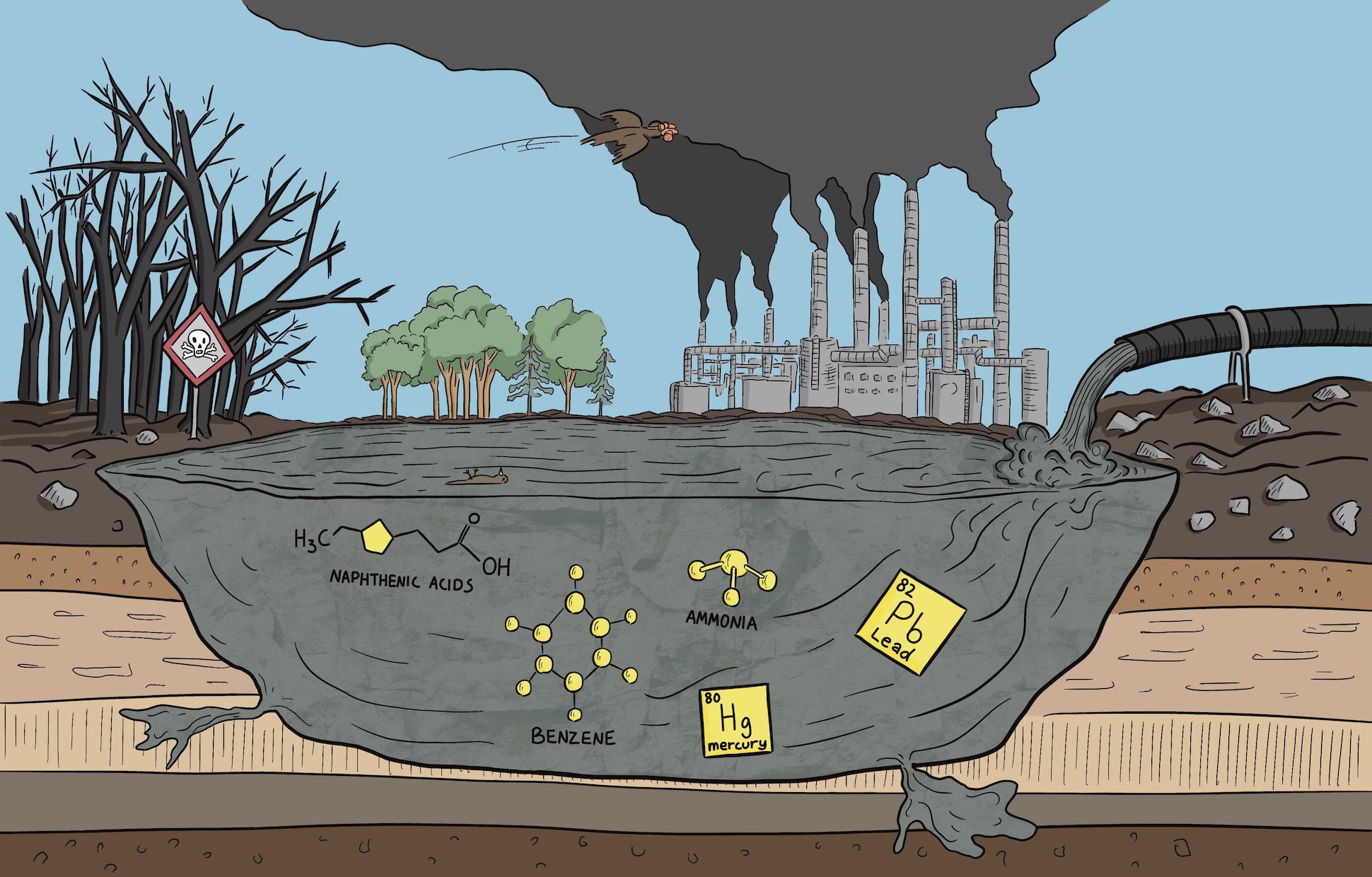

This report summarizes the serious negative environmental and social impacts of the oil sands tailings. The tailings “ponds” store acutely toxic chemicals, including high concentrations of dangerous naphthenic acids, and are known to leak and evaporate their content into the surrounding environment.

The tailings “ponds” also impact the boreal forest’s biodiversity and are especially lethal to migratory birds who land and perish in the tailings “ponds” during migration season.

The oil industry has put aside only a small fraction of the officially estimated $28 billion it will cost to clean up the oil sands tailings. Experts believe the actual cost figure could be four times as large.

The report also weaves Indigenous Knowledge and shares the experiences of Indigenous experts from downstream communities who have been deeply impacted by the ever-growing oil sands industry. They share the many ways the upstream devastation has fractured the connection between community members, water, wildlife and their traditional practices.

Despite the risks to environment and downstream communities, the oil sands tailings volume and area was allowed to massively balloon from 1975 to 2020.

Average 5-year growth of fluid tailings from 1980 to 2005

Average 5-year tailings growth rate from 2005 onwards

Tailings are the waste of the oil sands extraction process - a byproduct of separating bitumen from clay, sand and silt using high volumes of water and chemicals. They are stored as large reservoirs of fluids using dams and built-up walls, which industry calls “ponds.” Oil sands tailings are acutely toxic. Despite what the term tailings “ponds” might suggest, there are over 1.4 trillion litres of tailings perched in “ponds” on the shores of the Athabasca River near Fort McMurray, Alberta.

Tailings “ponds” are immense open-air reservoirs designed for solids to settle to the bottom of the ponds and separate from the water over long periods of time. After the water has separated from the solids, it can then be recycled in industrial operations. However, not all the solids easily settle. Instead, many remain suspended in the water, and it is estimated that they can take up to 150 years to settle naturally and completely separate. This extremely slow settlement process is a problem because industry has not shown they can safely store tailings for that long without causing environmental harm.

The environmental impacts of tailings ponds on the landscape are pervasive. Tailings leak toxic substances, emit greenhouse gasses, require the removal of carbon-storing peatlands and forests, and harm wildlife who mistake them for natural bodies of water.

Despite the risks to environment and downstream communities from storing dangerous waste in tailings ponds, and the lack of meaningful reclamation success, the oil sands tailings volume and area was allowed to massively balloon from 1975 to 2020:

Today, there is ongoing harm that results in a loss of access to traditional lands by Indigenous communities, which disrupts their traditional ways of life. Land-based teaching, hunting and fishing, medicine harvesting, and community gatherings are all traditional practices fundamental to the Indigenous people in the area that are now nearly impossible to carry out. For example, gathering sites that once hosted many generations have become “no access zones” by industrial operators. The obstruction of access, and thus obstruction of traditional practices, is a direct attack on the Indigeneity of the communities surrounding and downstream of the oil sands.

Connection to the land and the animals is a central part of Indigenous peoples’ identity, and being separated from these deeply affects mental health. For example, Jean longs and mourns for access to food and fur like her ancestors did. After living many years in traditional ways further up North, Jean returned to Fort McKay to be close to her parents and describes a real “culture shock” upon witnessing the devastation and the lack of access.

Oil production is responsible for the erosion of connection to culture and tradition, through the destruction of the relationship between people and ecosystems. Land-based teaching, hunting and fishing, medicine harvesting, and community gatherings are all traditional practices fundamental to the Indigenous people in the area that are harmed by the industrial activities in the region.

Given the enormity of the environmental impacts on downstream and nearby, predominantly Indigenous communities of the oil sands region, and the enormous risk held by the general public in clean-up costs for reclaiming tailings ponds, it is evident that any solutions for tailings management must be supported by downstream communities and the public.

Develop and implement a comprehensive tailings reclamation plan for the oil sands region, prioritizing environmental outcomes and the concerns of impacted downstream communities.

Require the collection and holding of the total funds that will be required for oil sands mine clean up and rehabilitation.

Uphold the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and respect Indigenous sovereignty.

Strengthen cross-jurisdictional collaboration with all levels of government on the management of tailings.

Strengthen the oil sands bird monitoring program so it is a transparent, standardized and collaborative program.

Let's take action!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Produced by ENVIRONMENTAL DEFENCE and CANADIAN PARKS AND WILDERNESS SOCIETY NORTHERN ALBERTA. Researched and written by Alienor Rougeot and Gillian Chow-Fraser, with contributions by Alex Ross and Paula Gray. For full list of contributors please download the report.

Special thanks to Jesse Cardinal, Jean L’Hommecourt and Mike Mercredi.

© Copyright May 2022 by ENVIRONMENTAL DEFENCE CANADA and CANADIAN PARKS AND WILDERNESS SOCIETY NORTHERN ALBERTA.

Permission is granted to the public to reproduce or disseminate this report, in part, or in whole, free of charge, in any format or medium without requiring specific permission. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of ENVIRONMENTAL DEFENCE CANADA.