This is a Guest Blog Post by Andrew Jennings

Every year, up to 170 million birds migrate or breed in Alberta’s Peace-Athabasca Delta region, home to the infamous tar sands and their tailings ponds – huge lakes of toxic waste produced by the oil extraction process.

Approximately 200,000 birds from 130 protected species from around the world land in tar sands tailings ponds every year, exposing them to life-threatening health risks. Migratory birds from all corners of North America are facing an unprecedented crisis in Alberta’s Peace-Athabasca Delta. Canada must act now to protect the biodiversity that is vital to our national environmental health and heritage.

Toxic Tailings Ponds are Responsible for Thousands of Bird Deaths

After weeks of flying thousands of kilometers across North America, exhausted birds often mistake these industry-made ponds for natural lakes and land on them to rest and refuel. Once they land, they become coated in the thick, oily substances contained in the toxic tailings. This can be lethal. A well-publicized example of this recurring tragedy occurred in 2008, when 1,600 ducks perished after mistaking a Syncrude tailings pond for a safe resting spot. There are several reasons why these tailings are deadly to birds:

- The oily content from the ponds weighs the birds down, preventing them from flying away and causing them to drown.

- Oil makes birds’ feathers less insulating, leading them to lose body heat and die from hypothermia.

- When birds attempt to clean the oil off their feathers by grooming themselves with their beaks (a process called preening), they ingest deadly toxins.

Coming into contact with the oily waste in tar sands tailing ponds can also lead to long-term health problems. These problems include mothers laying fewer eggs, abnormalities in embryos, slower growth in young birds, and higher than normal death rates. So far, this exposure has caused deaths in 43 different species of protected migratory birds.

The Oil Industry Isn’t Doing What is Needed to Prevent Bird Deaths

Even though the tar sands industry uses bird deterrent systems like noise cannons to keep birds away, these systems are not very effective. Many birds continue to land in ponds that have these systems in place.

The Alberta Energy Regulator, the government agency in charge of managing the development of energy resources, ordered a study to check the effectiveness of bird deterrent systems. Colleen Cassady St. Clair, the professor who led the study, found that these systems “[maximize] the appearance of bird protection while appearing to impede actual bird protection.” However, this information was not made public until journalists got hold of the study through a freedom of information request and reported on it.

Oil production is destroying North America’s most important nesting ground for birds

Birds landing in tailings isn’t the only way oil production in the tar sands harms birds. Tailings ponds take up so much space – over 300 sq-km in 2023 – that they’ve destroyed critical habitats for migratory birds. For instance, every 2.5 sq-km of boreal forest can support up to 500 breeding pairs of migratory birds. Therefore, these industrial developments are displacing tens of thousands of birds. This is particularly concerning given the ecological significance of the region: the Peace-Athabasca Delta is a globally recognized wetland, and the adjacent Wood Buffalo National Park is a UNESCO World Heritage site celebrated for its rich biodiversity.

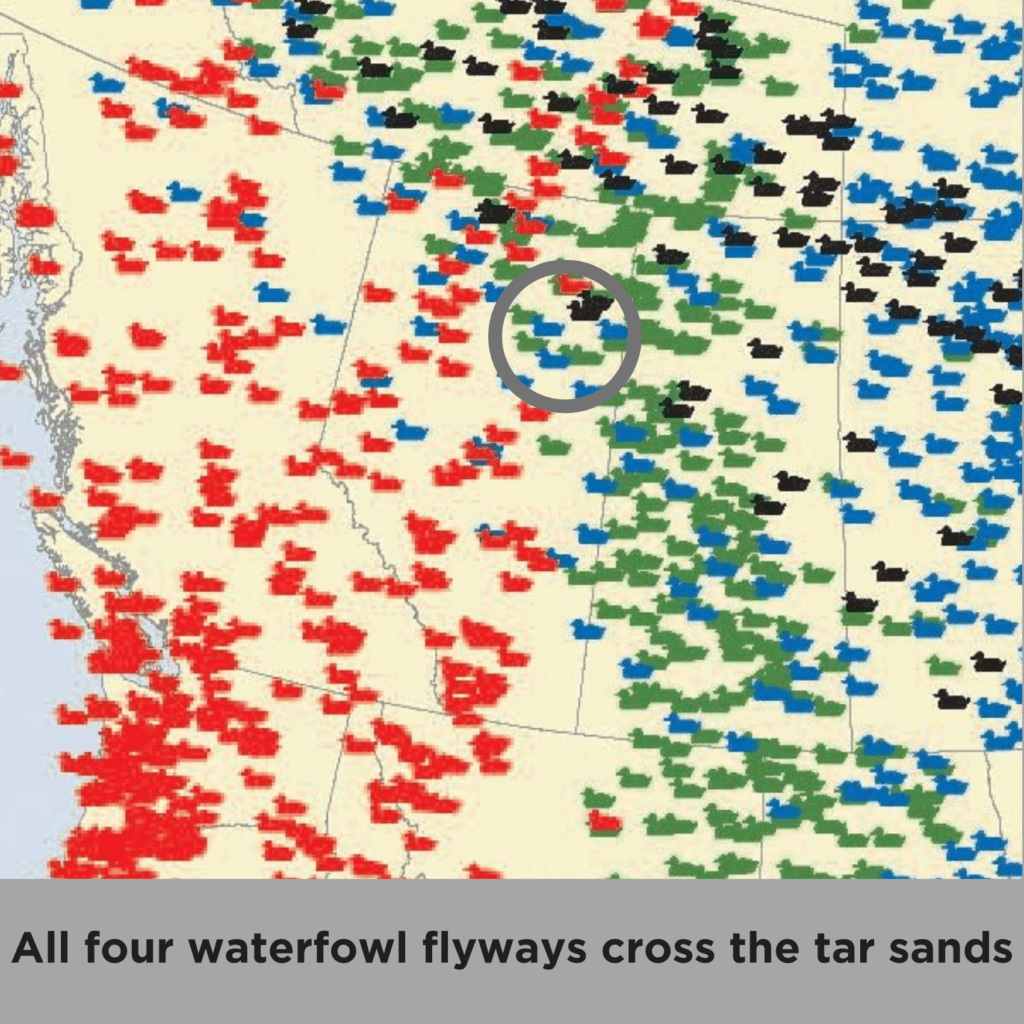

The region is North America’s most important nesting and staging ground for birds. All four of North America’s migratory flyways converge on the Peace-Athabasca Delta, which is the world’s largest inland delta. The delta supports almost half a million birds during spring migration and over one million in the fall, including the critically endangered Whooping Crane and the nationally vulnerable Tundra Peregrine Falcon.

Deforestation and industrial development break up the natural areas birds need for migration, making their journeys more challenging. This forces birds to fly longer routes around damaged and inhospitable environments, using up more energy. In addition, the large amount of water used by tar sands operations lowers local water levels, harming the wetlands and marshes that migratory birds rely on.

Since oil production in the tar sands started on a large scale, at least nine protected bird species in the tar sands have experienced a population decline of over fifty per cent! The Lesser Scaup, one of the biggest victims of tailing ponds, has had its population plummet by up to seventy per cent over the last thirty years. Some species, like the elegant Whooping Crane, are even more vulnerable. With a global population of only about five hundred, these cranes migrate through the region twice a year. A decline similar to that of the Lesser Scaup could be catastrophic for the iconic species.

Species like the Whooping Crane and the Tundra Peregrine Falcon are in a race against the clock; the tar sands and their tailings ponds grow larger every day, pushing them closer to extinction.

At the COP15 summit in Montreal, Canada made large commitments to biodiversity conservation, presenting itself as a global leader in the cause. However, actions in Alberta tell a different story. The Federal Government must act immediately to safeguard bird habitats and put an end to the toxic takeover in the tar sands. This will ensure that these species, and all others protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act and Species at Risk Act, have a long future in Canada.

We cannot ignore the tarry threat these precious species face – take action now.

Andrew Jennings is a fourth-year history student at the University of Toronto, studying history with a focus in law and the history of science. A lifelong birder, he aims to apply his love for the outdoors in a career in environmental law.

Andrew Jennings is a fourth-year history student at the University of Toronto, studying history with a focus in law and the history of science. A lifelong birder, he aims to apply his love for the outdoors in a career in environmental law.