Last week in Illinois, a carbon capture project was found to be leaking.

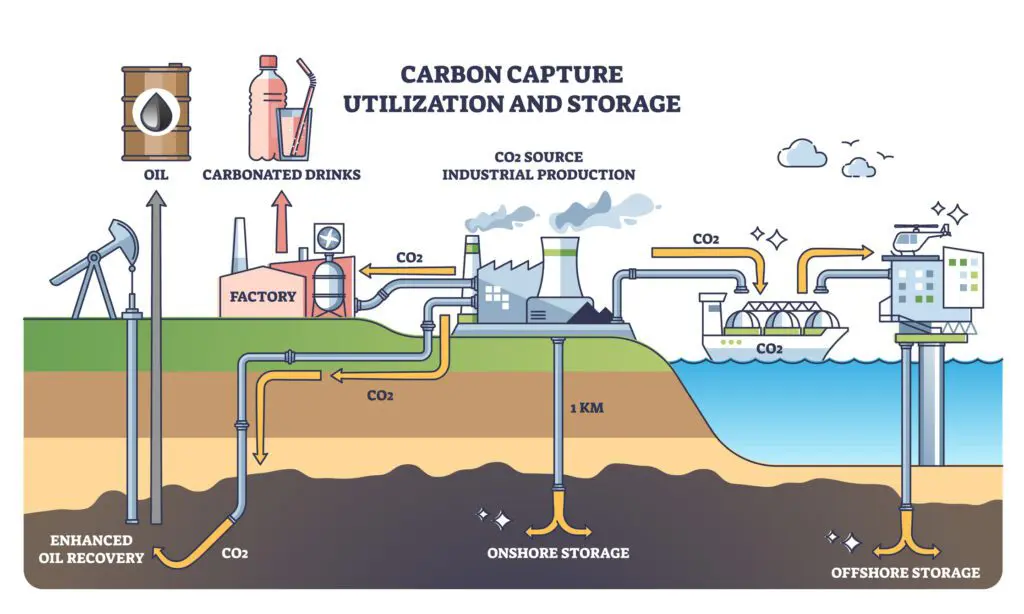

Carbon capture is the process of capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) from where it is being released, such as a power plant or refinery.

Though most of the carbon being captured is used to pump out more oil, small amounts are being stored underground. In this case, the CO2 must be compressed and liquified, so that it can be transported through pipelines to injection wells.

The leak happened at an injection well – which is where compressed carbon dioxide is pumped underground. This is the first injection well for permanent geologic storage in the United States.

The cause? Corrosion.

The leak occurred about five miles outside of a critical aquifer. Leaks like this put underground aquifers at risk, jeopardizing sources of drinking water. That’s because an increase in CO2 can cause leaching of lead and arsenic contained in rocks into the groundwater.

It’s the reason that in Australia, farmers led the charge and got carbon storage banned in the country’s largest groundwater basin.

We know that carbon capture isn’t an effective climate solution, and is being used by the oil and gas industry to greenwash their business. However – as this leak shows – the problem is even worse, given the risk to public health and safety posed by carbon capture projects.

It’s not just injection wells that can leak. In the United States, there have been over 100 leaks or ruptures on existing carbon pipelines since 2004. In response, numerous counties have passed temporary moratoriums on carbon pipelines given the health and safety risks.

Carbon capture projects are being proposed across Canada. The largest project is being pushed for by the Pathways Alliance – a coalition of the largest tar sands companies. They’re proposed storage site is two times the size of the city of Calgary – and will require nearly 20 injection wells.

Carbon capture projects are being proposed across Canada. The largest project is being pushed for by the Pathways Alliance – a coalition of the largest tar sands companies. They’re proposed storage site is two times the size of the city of Calgary – and will require nearly 20 injection wells.

Yet, little information is being shared with impacted Indigenous communities and other frontline communities about the types of risks these projects introduce.

Clearly, it’s not a matter of if carbon capture facilities leak, but rather when.

Take Action: Tell Canada to Stop Big Oil from Polluting our Climate