The federal government is currently considering whether to reject or approve Teck’s proposed Frontier Oilsands Mine. This large open pit bitumen mine will have lasting harmful impacts to wildlife habitat. It will cause further loss of northeast Alberta’s biodiversity- the diverse wealth of native species and ecosystems that both Alberta and Canada have committed to maintain for future generations.

The federal-provincial regulatory panel that reviewed the Frontier mine concluded it would mean ‘significant adverse effects’ to biodiversity, locally and also regionally, considering the combined impacts of this mine and other industrial projects. The regulatory panel added that “the proposed mitigation measures have not been proven to be effective or to fully mitigate project effects on the environment or on Indigenous rights, use of lands and resources, and culture.”

What is at risk from the Frontier mine?

Wood bison, and the communities that rely on them

For a start, a herd of wood bison called the Ronald Lake bison is at risk. They are special because they are free from the diseases of bovine tuberculosis and brucellosis that were introduced in the 20th century to wood bison herds further north, inside Wood Buffalo National Park. Local First Nations rely upon these disease-free bison for part of their food security. The mine would destroy or block the south part of the Ronald Lake bison range. They could be pushed into poorer habitat and into contact with the diseased herds, which would jeopardize their health, numbers and value to Indigenous communities.

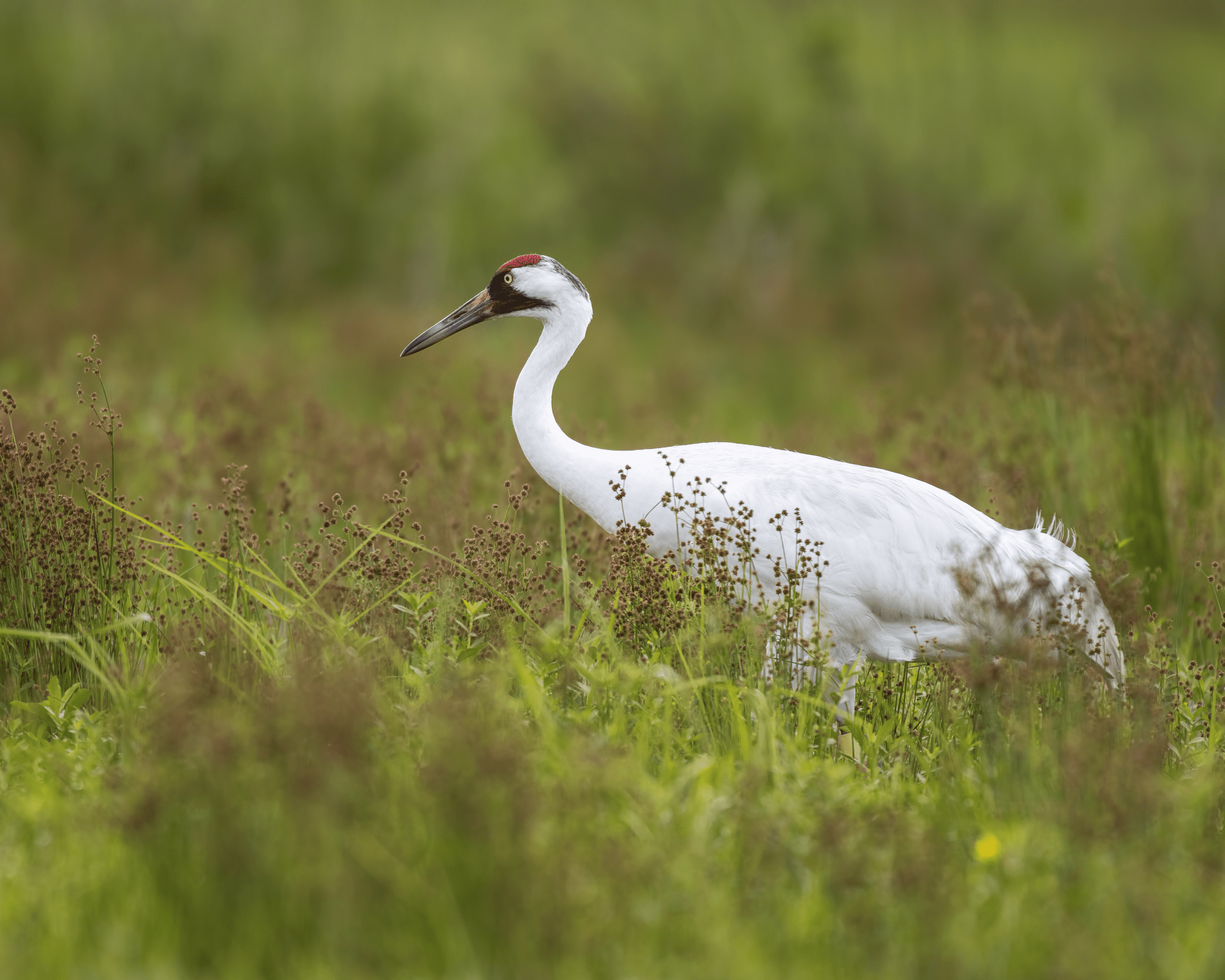

Migratory birds

Teck Frontier’s lease sits beside the Athabasca River just south of the Peace-Athabasca Delta, along a major North American migratory flyway. The Delta is one of the world’s largest freshwater deltas and supports globally significant waterfowl populations. Alberta Wilderness Association (AWA) is concerned that migratory birds, including endangered whooping cranes, may be harmed by the increased toxicity of industrial lands and waters on the nearby mine site.

Critical – and irreplaceable – wetlands

Wetlands are a key part of Alberta boreal ecosystems, storing carbon and water, and providing valuable wildlife habitat. They make up just under half the landscape on the Teck Frontier site. Alberta has exempted oil sands industry applications, up to and including the Frontier mine, from the provincial wetland policy.

The site’s peat wetlands, such as bogs and fens, will be gone forever, as they cannot be reclaimed once they’re destroyed by a mine. Some swamps and marshes are planned to be re-built eventually, but at lower density than today. Re-creating water flows that support wetlands on mine sites is difficult, and toxic soils from salts and hydrocarbons add to the risk that reclaimed wetlands in the mineable oilsands region will be greatly impaired compared to natural wetlands. This is bad news, not just for sensitive wetland birds like the yellow rail and rusty blackbird, but for the whole regional ecosystem’s diversity and ability to retain water.

Boreal forest, and the animals that live there

Forests will be removed on the mine site for many decades. For the forest dwelling Canada lynx, industrial disturbance in the wider region is already having a significantly adverse impact on their habitat, and the Teck mine will add to that. Old forests will be gone on-site for more than a century; whether they return to their former diversity and complexity is uncertain. This is harmful to valued fur-bearers such as marten and fisher and to sensitive older forest bird specialists like the mighty northern goshawk or the beautiful Canada warbler.

Will mine operators even stick around to do the clean up?

Another serious problem for regional wildlife is the likelihood that oilsands mines will default on their reclamation (or clean-up) obligations. Alberta’s regulations only require these mines to post a small financial security deposit now against their current reclamation obligations, and to ramp up payments 15 years before the end-of-mine life.

The theory is, big companies with high assets now will pay up in future decades. But why would investors in this sunset industry pay billions to reclaim a site long after its main revenue-earning years are over? Alberta now holds only about $1 billion in oil sands mine clean-up funds. That’s three percent of operators’ self-calculated clean-up costs of $31 billion, and less than 1 percent of the Alberta Energy Regulator’s internal clean-up cost estimates of $130 billion as of 2018. Quebec and Yukon each have stronger up-front financial security requirements to motivate timely, progressive mine reclamation. Alberta’s unfunded reclamation liabilities mean un-reclaimed landscapes may well become a long-term ecological hazard and public burden.

The Teck Frontier mine proposal, nested within Alberta’s deficient regulatory system, falls far short of responsible resource development. It should be rejected by the Canadian government.

Carolyn Campbell is a Conservation Specialist with Alberta Wilderness Association. Since 1965, AWA has inspired communities to care for Alberta’s wild spaces through awareness and action.