As part of the efforts to combat climate change, governments around the world are putting a price on carbon pollution, making polluters pay for the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions they pump into the atmosphere.

Let’s be clear – carbon pricing isn’t a silver bullet solution. But it is catching on as a market-based tool to lower GHG emissions, with over 70 jurisdictions including Canada now using it in some form. Here’s a quick summary of what you need to know.

Why on earth would carbon need a price on it?

You probably already know that greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide are building up at an alarming rate, causing increasingly catastrophic climate change. This is no longer theoretical: atmospheric carbon has reached its highest level in 800,000 years, and the impacts are already causing starvation, disease, death, and other very bad things.

To stop this from getting worse and killing literally everything, we need to drastically cut carbon emissions. To do this, we need system-wide tools to gradually, but meaningfully, shift away from fossil fuels to a cleaner economy without causing economic chaos.

How does carbon pricing slow down climate change?

In a nutshell, putting a price on carbon emissions means that it costs something to pollute. This cost ensures that polluters don’t get a free pass to emit carbon, leaving society to foot the massive bills for the impacts of climate change, including more extreme weather, increased disease, and a host of other costs we’re already paying. That doesn’t sound fair, does it?

Reflecting even a small part of the real cost of carbon pollution also gives companies, governments, and individuals an incentive to cut their carbon emissions and move to cleaner energy. Since fossil fuels become more expensive, the price gap shrinks between clean energy sources like solar power and cheap polluting sources like coal.

Results from around the world, including from within Canada, decisively show that a price on pollution works. British Columbia has had a carbon tax in place for over a decade. While the economy boomed and population grew, the carbon tax lowered per capita gasoline, diesel, and natural gas consumption. In Britain, a price on carbon prompted electric utilities to switch away from coal, and emissions have fallen to their lowest level since 1890. Other countries have also curbed their emissions with a price on carbon, including Sweden, Finland, Denmark, the Netherlands, several American states, and the European Union. When high-emitting countries successfully reduce carbon pollution, climate change slows down.

How is carbon pricing implemented?

Governments can choose from a few different systems – a carbon tax, cap-and-trade, carbon fee and dividend, or their own home-cooked combination of these. There’s no simple answer to which system is best, but evidence is emerging that shows the economic and carbon reduction impacts of each. More on that here.

In most systems, the price rises over time, gradually approaching the price it actually costs society to emit that tonne of carbon (a hotly debated number). Fun fact: current carbon prices in Canada are hovering around $20 or $30 per tonne depending on where you live, far below what these emissions cost society to deal with. Systems with lower prices are often less politically risky, but need to be combined with a whole range of actions to reduce emissions on top of pricing carbon. Since Canada’s price would have to be close to $200 per tonne to meet our goals without any other actions, all levels of government need strong programs to reduce GHG emissions alongside carbon pricing.

There are many ways to use carbon pricing revenues, like incentive programs to help people and companies reduce emissions, or tax rebates. But in most systems, the main goal is not to raise money, but to discourage pollution by bringing it closer to its real cost. A perfect carbon pricing system would change behaviour to reduce carbon emissions to zero, and yield no profits.

How does Canada’s federal carbon price work?

Canada’s federal government has put a price on carbon pollution in all provinces where there isn’t one already. This means that you pay a few cents more for gasoline, home heating fuels, and other fossil fuel burning activities, because these activities cause climate change, which is becoming very expensive.

It’s pretty simple: if you pollute more, you pay more. This price will gradually increase every year, along with the rebate you’ll get to help cover the cost. Big industrial polluters will also have to pay, but they’re part of a separate system meant to make sure they don’t pack up and leave to pollute elsewhere for cheaper.

Most of the revenue from the federal price on pollution goes right back to households through tax rebates. You may have already received this rebate. Most households will get back more than they pay.

If the money goes right back to households, is a price on carbon still effective ?

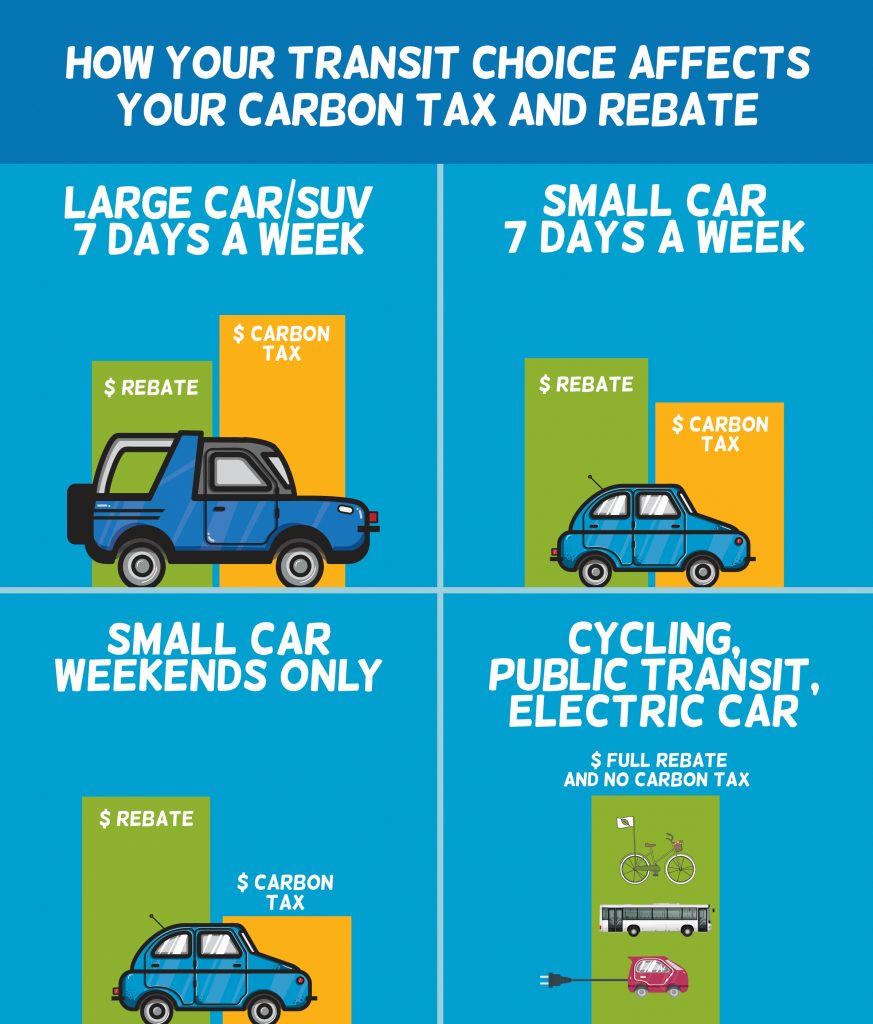

Here’s how it works: the amount you pay from the carbon price throughout the year depends on how much you pollute. But the rebate the government returns to you does not. You get a fixed rebate amount based on what an “average” household would pay in increased costs from the price on carbon (about $300 for a household in Ontario). This amount changes depending on which province you live in, since not everyone will face the same costs.

By giving back a standard amount, this means that only those who pollute more than average will actually see an increase in costs. Those who take action to reduce their polluting behaviour to below average will get more money back than they paid in increased costs. This is a financial reward for taking deeper action.

Will carbon pricing mean I pay more for things like gasoline and electricity?

Carbon pricing makes using fossil fuels more expensive. That’s the whole idea – to shift behaviours away from polluting actions that cause climate change. Whether or not you pay more depends on how you react to this gradual increase in price. Ideally, you find ways to use fewer fossil fuels. Maybe you install a smart thermostat to save energy in your home. Maybe you think twice about idling your car in the school parking lot, because gasoline costs a few cents per litre more. Maybe you ride a bike to work instead of driving when it’s nice out.

The price on carbon is not meant to break the bank for average energy users. But it is meant to encourage people to think more about their consumption.

Is carbon pricing enough to deal with climate change?

Absolutely not. Unless prices rise drastically, carbon pricing will not reduce greenhouse gas emissions enough to avoid catastrophic climate change. This is like trying to renovate a house with a screwdriver. A useful tool, but not up to the job without a whole box of other tools. In addition to carbon pricing, we need strong regulations, forward-thinking policies, comprehensive programs to encourage and incentivize behaviour change, and much more action from governments to fight climate change.

Here’s the good news: research from two of Canada’s leading environmental economists shows that meeting Canada’s Paris Agreement commitments on climate change will have virtually no impact on our continued economic growth. We’ll see 38 per cent GDP growth by 2030 with carbon pricing and other strong policies, vs. 39 per cent GDP growth if Canada takes no action at all. Canada is well positioned to take stronger action to reduce carbon pollution without harming the economy.