Ontario’s and Saskatchewan’s top courts have delivered a strong climate change reality check: a price on carbon pollution is essential, constitutional, and not a tax.

Unhappy with their province’s top court judgments, the Saskatchewan and Ontario governments say this will bring their cases to the Supreme Court. So what does this legal battle mean for climate change action, and how will it play out in the year ahead?

What the top courts in Ontario & Saskatchewan decided

The legal question before the courts was whether the federal law putting a price on carbon pollution is constitutional. The answer: it is. Both courts separately upheld the law under the federal government’s Peace, Order and Good Government powers after their respective provincial governments claimed it was unconstitutional.

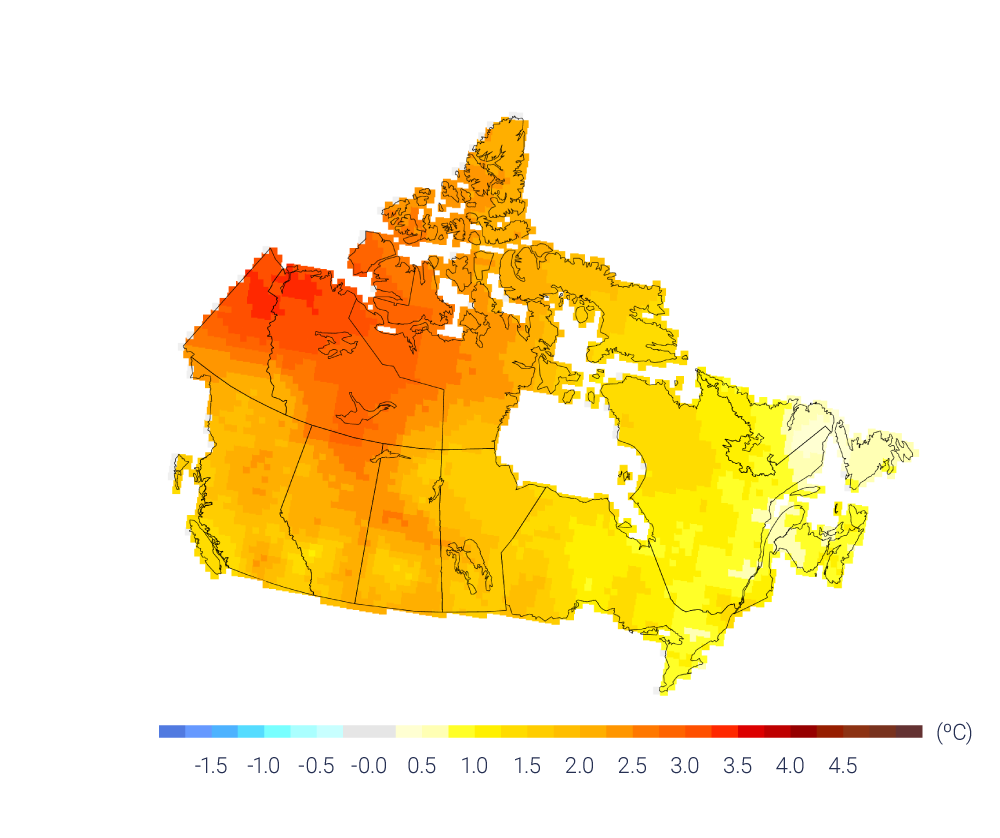

In a nutshell, they’ve ruled that faced with the devastating impacts Canadians are facing, and the fact that we’re warming at twice the global average, the federal government’s action to set a minimum price on carbon pollution when provinces refuse to do it is a legitimate and lawful response.

Climate change doesn’t fall under any single government’s power to act. It’s actually the opposite: all governments have to act. But there is a demonstrated need for a “collective approach to a matter of national concern” from the federal government to address nation-wide, collective impacts. The Ontario ruling explains that “the need for a collective approach to a matter of national concern, and the risk of non-participation by one or more provinces, permits Canada to adopt minimum national standards to reduce GHG [Greenhouse Gas] emissions.”

This means that a piecemeal, province-by-province approach is not good enough for a crisis this urgent, particularly when some provinces may fail to act at all.

Why this is important for climate action in Canada?

What’s notable about these top court decisions is how many pages they’ve devoted to the urgency of the climate crisis, and why climate change is a “national concern.” Saskatchewan’s decision, delivered a few months before Ontario’s, concluded that climate change constitutes an emergency and “presents a genuine threat to Canada,” as well as being “one of the great existential issues of our time.”

I read the 93-page Ontario Court of Appeal decision document while on a conference call with our climate change campaign team and our lawyers. We pored through page after page, struck by the blunt honesty of the court’s words. They cited “uncontested evidence” that climate change is leading to more wildfires, floods, new diseases, and extinctions on a scale we’ve never seen before, and that climate change “has had a particularly serious impact on some Indigenous communities in Canada.”

This was not legalese. This was clear, pointed language from top court officials acknowledging that we are in a massive climate crisis requiring an unprecedented response. Take this passage from Ontario’s decision:

“Both nationally and globally, the economic and human costs of climate change are considerable. Canada’s Minister of Finance has estimated that climate change will cost Canada’s economy $5 billion per year by 2020, and up to $43 billion per year by 2050 if no action is taken to mitigate its effects. The World Health Organization has estimated that climate change is currently causing the deaths of 150,000 people worldwide each year. Rising sea levels threaten the safety and lives of tens of millions of people in vulnerable regions.”

After a year of watching the plain facts of climate change get spun and twisted by posturing and rhetoric, this level of honesty felt like a triumph.

The court decisions were also a reminder that carbon pricing is just the tip of the iceberg – an iceberg which is melting faster than anyone thought. People are already losing their homes, their health, their land, and their livelihoods. If governments at all levels are not acting to slow these impacts with every tool available, they are failing to protect the people who elected them.

If a province, like Ontario or Saskatchewan refuses to act in a crisis, we all suffer, because carbon pollution doesn’t respect borders. What’s really unfair is that Canada’s north and Atlantic region will be hardest hit by climate change while emitting the least carbon pollution, and “without a collective national response, all they can do is prepare for the worst.” That’s why the federal government needs the power to step in and set minimum standards for climate action, to ensure that all provinces are taking appropriate action.

What happens next?

Two top provincial courts have now upheld the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act. But it’s not over.

Both cases were quickly appealed, and are headed for the Supreme Court to make the final call on whether the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act is constitutional. Meanwhile, the Alberta and Manitoba governments have said they will also challenge federal carbon pricing in their respective province’s top courts. Interestingly, New Brunswick’s government has now abandoned their challenge, with Premier Higgs saying it “it wouldn’t make sense for me to … use taxpayer dollars to go and present the same case.”

But the federal election will come before any Supreme Court appeals are heard. As some parties have indicated that they would repeal carbon pricing if elected, the election outcome will determine if the federal government continues to put a price on pollution, even if the law is upheld by the Supreme Court. Still, any decision made by the Supreme Court would be an important reference case to guide how and where future governments can act on climate change.

The appeals are not unexpected. When Premier Moe and Premier Ford (and now Premier Kenney and Premier Pallister) launched these court challenges with great fanfare, it was clear they would use “every tool at their disposal” to block a price on pollution, and spend millions of public dollars bringing it all the way to Canada’s top court.

What they didn’t expect was such a comprehensive reinforcement from the courts of the need for strong climate action, and the power of the federal government to act and set a minimum price on carbon pollution in those provinces that refuse to take action.

You can find the Ontario Court of Appeal decision here, and the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal decision here.