The federal government gives polluters a free pass while it ignores the high cancer rates among some Alberta Indigenous communities. That’s how I’d sum up last week’s gravely disappointing explanation for why Canada sits by doing nothing while tar sands tailings ponds are leaking toxic chemicals into Alberta rivers such as the Athabasca River, Beaver Creek, and the Muskeg River.

In June of 2017, Environmental Defence, Natural Resources Defense Council, and Daniel T’seleie of the K’ahsho Got’ine Dene First Nation submitted a case to the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) the environmental arm of NAFTA. We argued that the federal government was failing to enforce the Fisheries Act with respect to tailings ponds that are leaking toxic chemicals into nearby rivers. The CEC ruled that our case had merit. And last week, the federal government responded.

The Canadian government did not deny that rivers, lakes, and groundwater were contaminated with the same toxins found in tailings ponds. But its nonchalant conclusion was that it could not determine whether that contamination came from tailings ponds or whether naturally occurring bitumen deposits were leaching chemicals into groundwater and surface water.

And yet the evidence in this case is so strong that it would be difficult to find a case that was more certain:

- Official documents from tar sands companies such as Suncor, Shell, and CNRL all state that their tailings will leak, and even estimate the leakage rate.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) inspectors have sampled several nearby rivers, lakes, and groundwater and found elevated levels of toxic chemicals such as arsenic, naphthenic acids, and vanadium, in some cases above the thresholds jointly established by provinces and the federal government.

- Research undertaken by federal government scientists and published in a peer-reviewed journal found that toxic chemicals found in groundwater flowing into the Athabasca River had the chemical “fingerprint” of chemicals found in tailings ponds. The scientists also concluded that the chemical makeup of the groundwater contamination was different than one would expect if it came from natural bitumen deposits.

To me, the government response seems like willful blindness rather than a true assessment of the situation based on the evidence.

Even worse, Environment and Climate Change Canada has already taken a step back on this issue. In 2014, because it didn’t have 100% certainty that the toxins in rivers came from tailings ponds, ECCC moved its enforcement officers to other areas. This means that the enforcement of Canada’s environmental laws with respect to water contamination from tailings ponds will only happen if someone makes a complaint.

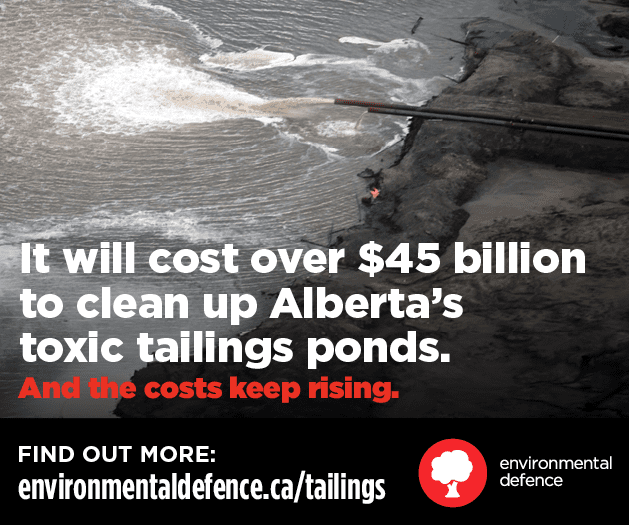

The precautionary principle adopted by the federal government states that in cases of serious environmental harm, uncertainty will not be used as a reason to postpone acting to protect the environment. I would call levels of toxins in water bodies that exceed safe thresholds and elevated cancer rates in Indigenous communities downstream of the tar sands serious environmental issues. And yet the decision not to prosecute oil giants under the Fisheries Act because of uncertainty shows blatant disregard for that principle and turns a blind eye to this grave problem.

The next step in this case is for the Commission for Environmental Cooperation to determine whether the case should go to a vote of the three NAFTA parties. The CEC had already determined that our case had merits, and I find it hard to believe the government’s response will change its opinion.

A better solution would be for the federal government immediately start working with the Alberta government to find a solution to this toxic legacy. The tar sands industry started creating tailing ponds fifty years ago. That should have been enough time for the industry to have developed a credible plan for managing tailings safely. The federal government must now enforce Canada’s environmental laws in order to protect freshwater, ecosystems, and the citizens of Alberta.