TransCanada better hold off on popping the Keystone XL (KXL) champagne. Last week’s decision by Nebraska regulators likely means years of uncertainty, regulatory delay, court challenges and additional costs and risks for the beleaguered pipeline.

Your news feed over the last week may have been filled with headlines about KXL receiving approval from the Nebraska Public Service Commission (PSC), clearing the pipeline’s final regulatory hurdle and paving the way for construction.

Not so fast.

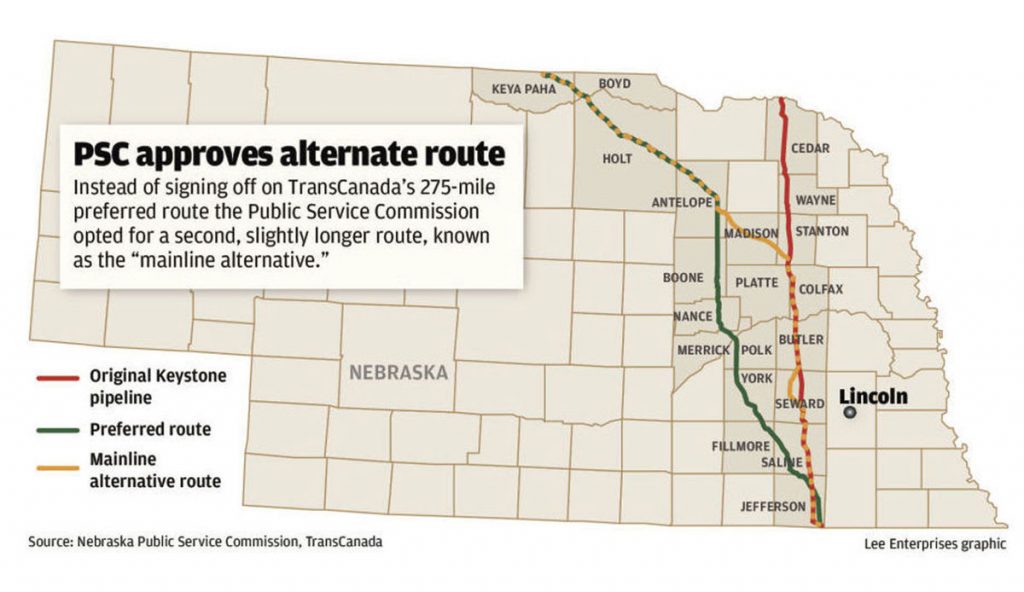

TransCanada’s proposed route through Nebraska as we’ve known it for the last nine years was actually unanimously rejected by the PSC last week. Instead, the PSC approved by a narrow margin an alternative KXL route through the state—the “Mainline Alternative”—a route that TransCanada never applied for and that never received proper assessments.

Here’s what the PSC decision really means for KXL:

- TransCanada may have to completely re-apply for approval from the PSC. The state regulator is by law required to either approve or deny an applied-for pipeline route, not consider an alternative option. This leaves the PSC’s decision open to legal challenges.

- The alternative route might not even work for TransCanada. In hearings before the PSC, TransCanada argued that the “Mainline Alternative” route was not feasible. That’s probably why TransCanada has already asked the PSC to address questions the company is raising about the alternative route.

- The PSC decision can be appealed, and likely will be. The appeal could turn into a long, bitter legal battle in Nebraska’s courts.

- The approved alternative route is nothing more than a line on a map as far as Nebraska landowners are concerned. TransCanada will now need to gain permission from a whole new set of landowners who may or may not want a tar sands pipeline crossing their farms and ranches.

- The Mainline Alternative will be further bogged down by Nebraska regulators. The state’s power commission will now need to study the need for six new pumping stations on the alternative route. And the Mainline Alternative crosses more of the Ogallala aquifer—a fragile ecosystem that provides clean groundwater for the U.S. Midwest—and impacts several endangered species that were less impacted by TransCanada’s preferred route, particularly the pallid sturgeon.

- The alternative route also means that the U.S. State Department, which granted KXL’s federal permit, must review the PSC’s decision. This opens up the possibility of the federal approval being withdrawn. Adding to TransCanada’s federal hurdles, a U.S. federal court ruled on Friday that a lawsuit brought by environmental groups and Native American tribes arguing that Keystone XL’s State Department approval relied on an outdated environmental review is allowed to proceed.

Considering the obstacle course of regulatory hurdles and legal challenges that the PSC just laid out for KXL, it’s not hard to see why TransCanada is not celebrating the Nebraska “approval”. TransCanada’s response to the PSC decision was notably muted and eerily similar to the company’s public statements in the months before it pulled the plug on Energy East. It’s also not hard to see why TransCanada’s stock barely budged after the news from Nebraska.

If I were a TransCanada shareholder, tar sands producer, or pipeline financier, I would certainly be nervous about the prospects for KXL. That may be why TransCanada executives wouldn’t commit to making a final investment decision on KXL at this week’s investors’ meeting, why the company is having trouble locking in tar sands shippers to fill the pipe, and why Moody’s Investors Service cast doubt on the project.

Even if the economic case for KXL brightens and it successfully navigates the minefield of regulatory and legal challenges, it still faces an unwavering coalition of landowners, farmers, ranchers, environmentalists and Native Americans determined to stop the project. Just last week, dozens of organizations and thousands of individuals signed the “Promise to Protect” – a commitment to peacefully resist the pipeline should construction proceed. And TransCanada is not doing itself any favours by spilling 800,000 litres of crude oil from its currently-operating Keystone I pipeline in South Dakota just days before the Nebraska decision.

The Nebraska PSC “approval” of Keystone XL is anything but. The pipeline faces years of delay and resistance in the courts, in regulatory hearings, and from grassroots opposition. The economics of Keystone XL are on thin ice, and last week’s decision only increases the risk.

Amidst the fallout of the Nebraska decision, is it only a matter of time before KXL follows in the footsteps of Energy East and gets abandoned by TransCanada?