Why do we need a climate change test?

In order for Canada to meet our goals to fight climate change, the government needs to make sure that the things our industries are building today will fit with a zero emissions future.

In order for Canada to meet our goals to fight climate change, the government needs to make sure that the things our industries are building today will fit with a zero emissions future.

Right now, there is no way of ensuring that the decisions that go into building a large-scale, long-lasting project such as a highway, a mine, a factory, or a pipeline, fit within Canada’s climate change goals, or if it will make economic sense in world that is increasing its efforts to greatly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, environmental assessments in Canada have long failed to ensure that project approvals are consistent with a climate-safe future.

The decisions made today with regards to Canada’s energy and industrial infrastructure will have consequences for generations to come. If every new major project is required to take a climate change test, we can make sure we’re only moving forward with projects that help us reach our future climate goals.

What is a climate change test?

A climate change test should be a key part of decision-making on new infrastructure projects. Every new energy or infrastructure proposal should be vetted based on our climate commitments.

A climate change test should be a key part of decision-making on new infrastructure projects. Every new energy or infrastructure proposal should be vetted based on our climate commitments.

The goal of the test should be to determine whether a project makes sense in a world that has agreed to the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees.

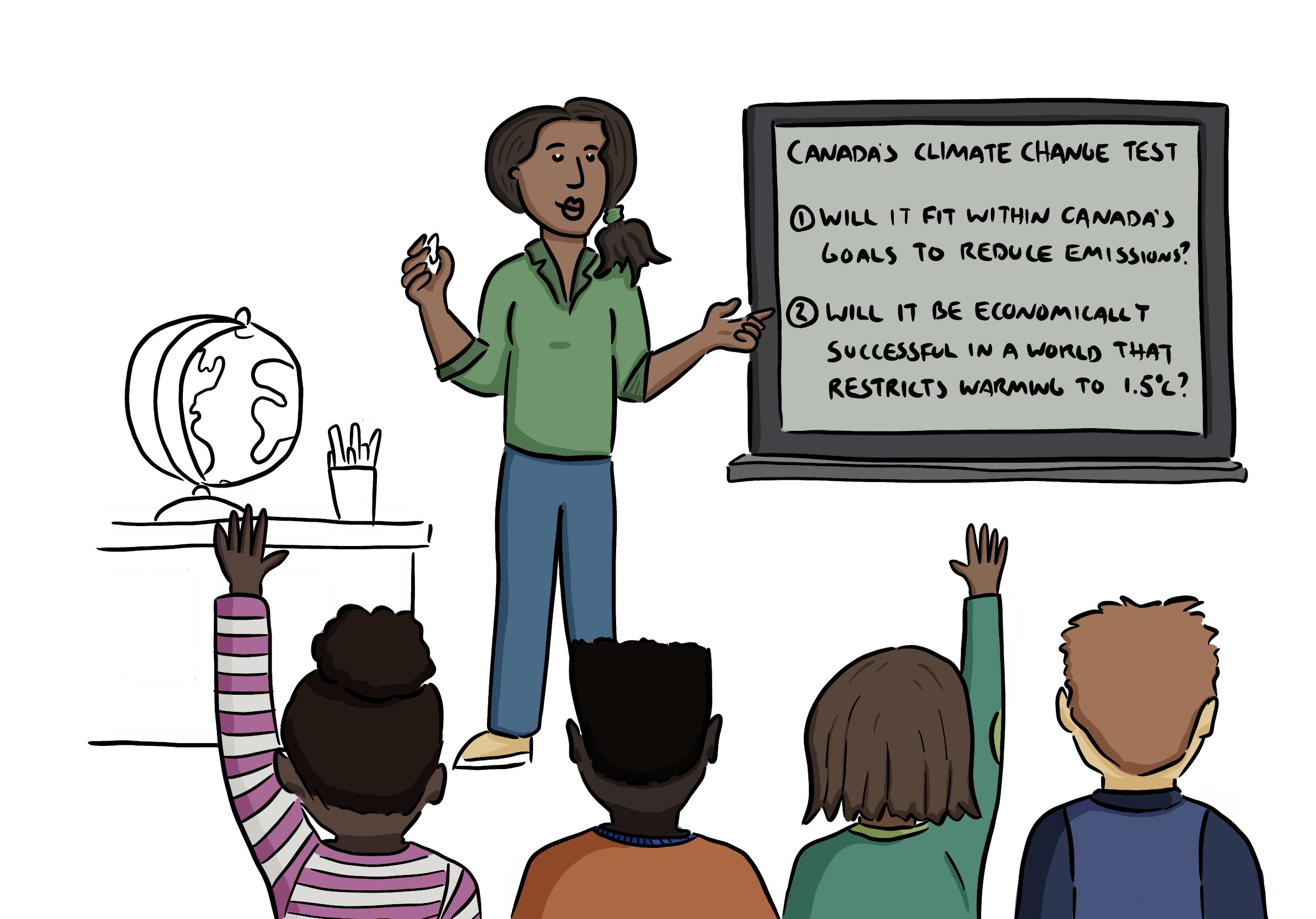

The test asks two questions:

1) Does a project’s emissions fit in with Canada’s goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions?

2) Will the project be economically successful in a future world transitioning away from fossil fuels?

The first part of the test would determine if a project’s full lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions (including downstream emissions) fit within Canada’s climate commitments. In order to answer the emissions part of the test, there are different tools that decision-makers can use. The most straightforward tool is a carbon budget (explained below).

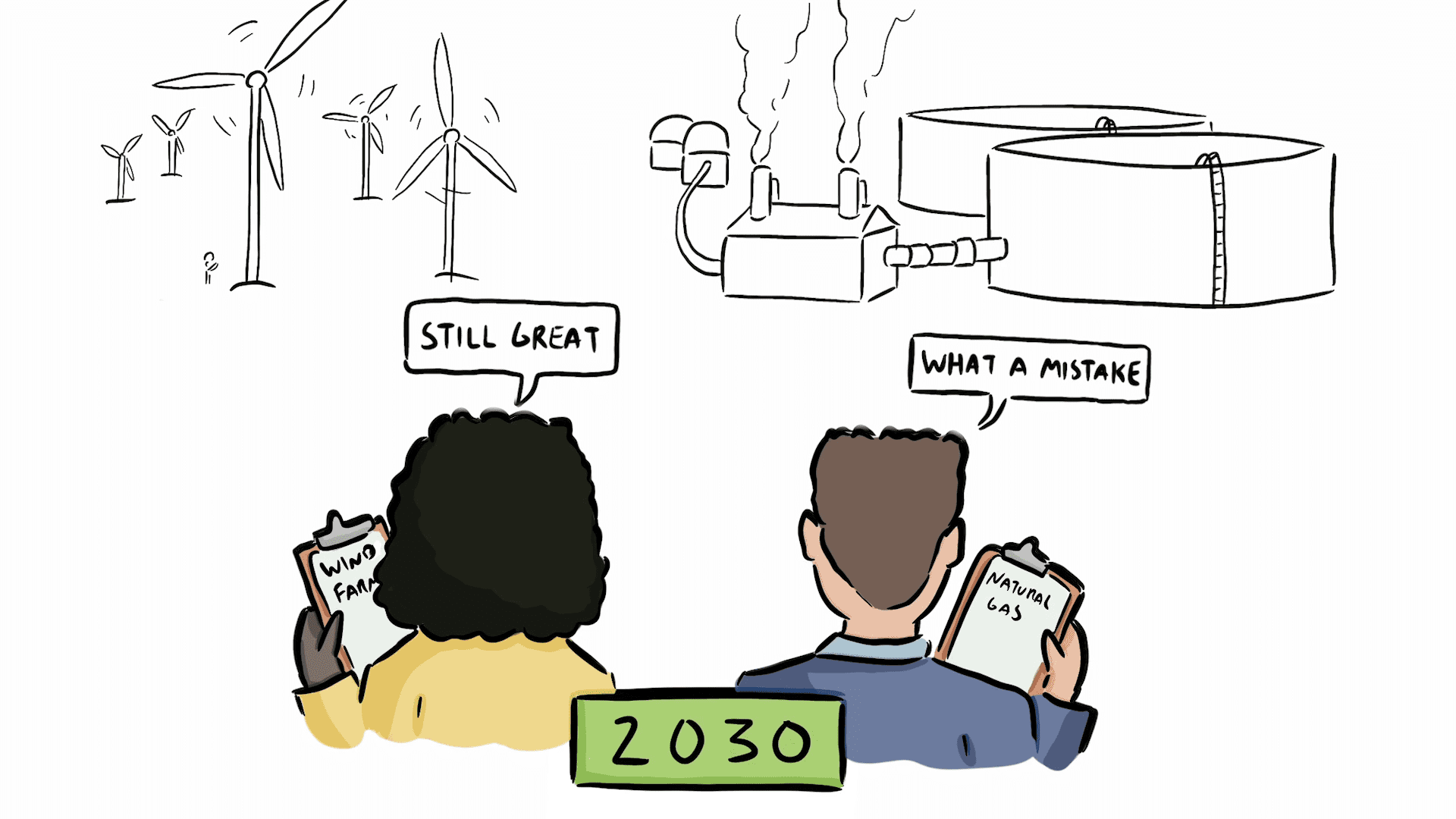

The second part of the climate test would determine if a project makes financial sense in a world that successfully tackles carbon pollution.

Because there is no climate change test, Canada is currently basing decisions on which infrastructure projects to approve using on the “business as usual” demand scenarios for fossil fuels. These scenarios suggest increased demand for decades to come, and are used to justify specific projects, rather than using scenarios consistent with the world’s transition away from fossil fuels. Continuing to use the “business as usual” scenario will result in climate catastrophe. Instead, we should be using economic models consistent with the world’s transition away from fossil fuels to determine whether new projects make economic sense.

If an infrastructure project only makes sense if it ignores climate change, it would fail the climate test.

What is a carbon budget?

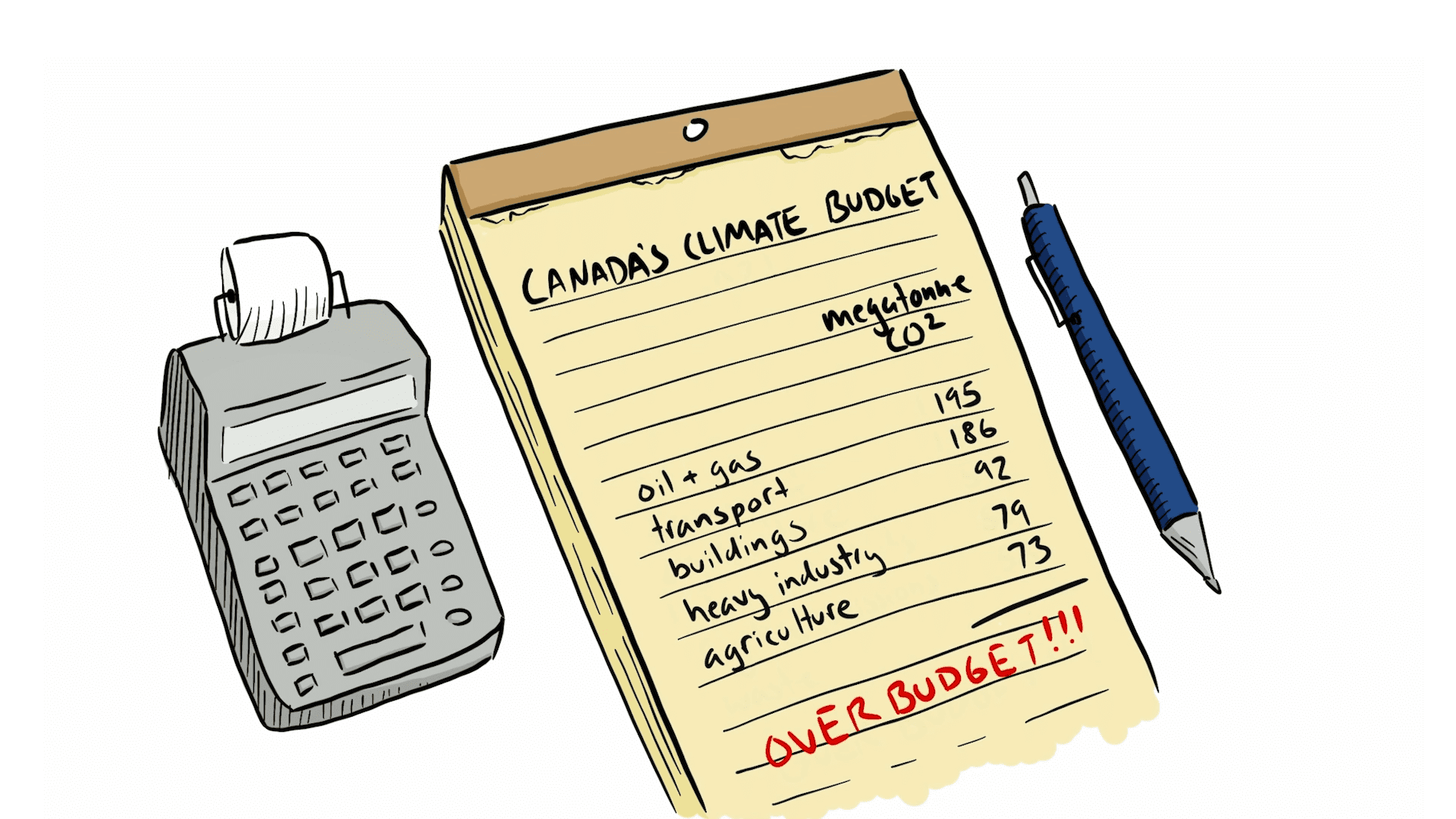

A “carbon budget” is a way of estimating how much more CO2 we can emit to the atmosphere before we raise global temperature above 1.5 degrees. It specifies the amount of emissions that Canada can produce over a specific time period en route to our long-term goal of reaching zero emissions by 2050.

A “carbon budget” is a way of estimating how much more CO2 we can emit to the atmosphere before we raise global temperature above 1.5 degrees. It specifies the amount of emissions that Canada can produce over a specific time period en route to our long-term goal of reaching zero emissions by 2050.

Just like a household budget, you only have so much to spend any given year – there’s only so much carbon we can emit each year without blowing the budget. And we have to decide how those emissions get allocated between the various sectors of our economy.

The difference is that with a climate budget we have less to spend each year – the goal is to move towards zero emissions by 2050. Also, carbon budgets don’t just operate on a year-to-year basis, but also consider how much we’ve already emitted in the past.

From our national carbon budget, we can also set budgets for provinces and individual sectors of the economy that decrease overtime in line with our national goals. A province with more people might have a higher budget allotment than a province with a lower population, for example.

We can use these budgets to weigh decisions about new infrastructure projects. A climate test would analyze greenhouse gas emissions related to a project (including upstream and downstream emissions) and assess whether it fits within the relevant budgets or not – just like you would when considering a new expense. If the pollution produced by a project breaks the “carbon budget”, then it would fail the climate test.

How we choose to spend and invest the remaining carbon in the budget will determine the available budget for future generations. Higher emissions this year, or in the next few years, imply more rapid cuts will be needed later. And the more we dip into the carbon piggy bank, the more serious climate impacts become.

Canada doesn’t have carbon budgets yet. Determining these budgets is a key part of developing a climate change test.

Check out this video from the Grantham Institute to learn more about carbon budgets.

What value does the climate change test provide?

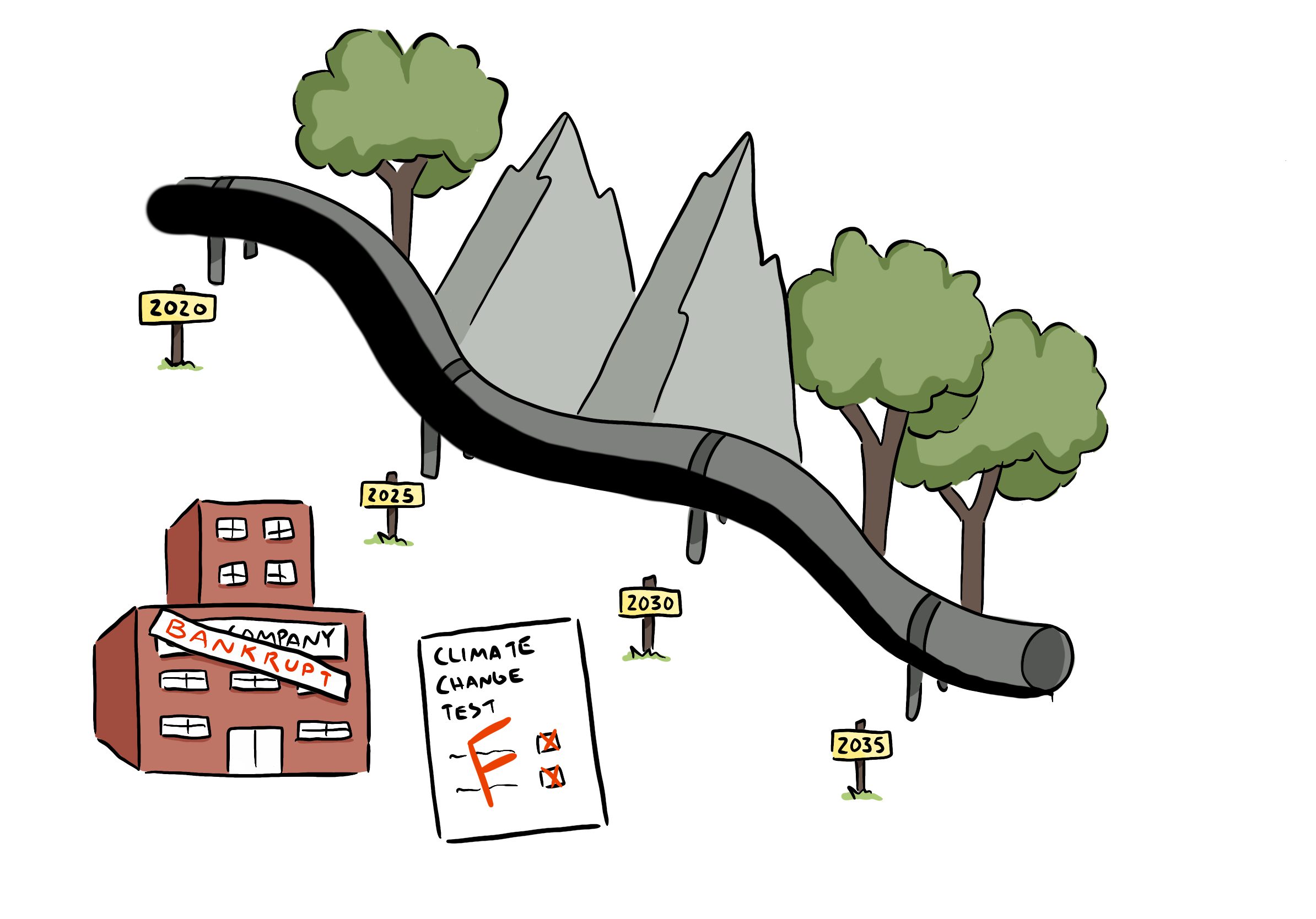

Canada has missed pretty much every climate change promise it has set. That’s because we set climate goals on one hand, and then when making decisions on whether to approve new things that create greenhouse gas emissions – like energy projects, pipelines or other major infrastructure projects – there’s no process for ensuring these decisions are compatible with Canada’s goals. And so the federal government is forging ahead with fossil fuel pipelines like the Coastal Gaslink Pipeline (despite opposition from the Wet’suwet’en First Nation) and the TransMountain pipeline (despite new analysis showing the pipeline makes no financial sense). And new climate bombs are moving through the impact assessment framework.

Canada has missed pretty much every climate change promise it has set. That’s because we set climate goals on one hand, and then when making decisions on whether to approve new things that create greenhouse gas emissions – like energy projects, pipelines or other major infrastructure projects – there’s no process for ensuring these decisions are compatible with Canada’s goals. And so the federal government is forging ahead with fossil fuel pipelines like the Coastal Gaslink Pipeline (despite opposition from the Wet’suwet’en First Nation) and the TransMountain pipeline (despite new analysis showing the pipeline makes no financial sense). And new climate bombs are moving through the impact assessment framework.

Canada’s federal government is fond of saying that we can build pipelines and still meet our climate promises. We have seen project after project approved with decision-makers making vague statements that they are consistent with our greenhouse gas reduction strategies – without any proof that those declarations are true. Is this political rhetoric or a legitimate argument? The way to answer that question is to apply the climate change test to all new major infrastructure projects in order to help determine which new energy and industrial projects make sense for Canada in a world moving away from fossil fuels.

In addition, a climate test would discourage companies from proposing projects that would become stranded assets as world markets increasingly move away from oil and gas.

When it comes to addressing the climate emergency – especially when we’re not on track to meet our targets – we need to be using every tool in the toolbox

What are the risks of not having a climate change test?

Without a climate test, we are setting ourselves up to fail at building an economy that makes sense in the next decade – and we’re setting ourselves up to fail at climate action. The United Nations Environment Program made it clear in its Production Gap report that Canada and other big emitters are planning to produce more than twice the amount of fossil fuels than what is consistent with a 1.5 degree future.

Without a climate test, we are setting ourselves up to fail at building an economy that makes sense in the next decade – and we’re setting ourselves up to fail at climate action. The United Nations Environment Program made it clear in its Production Gap report that Canada and other big emitters are planning to produce more than twice the amount of fossil fuels than what is consistent with a 1.5 degree future.

Right now, fossil fuel companies are trying to get three major carbon bombs approved, including:

- a proposed LNG pipeline in Quebec (Gazoduq) which in conjunction with the Énergie Saguenay LNG plant would produce 7.8 million tons of greenhouse gas annually

- an expansion of the Vista thermal coal mine, already Canada’s largest thermal coal mine; and

- a huge expansion of a tar sands mine by Suncor Energy which would produce another 3 million tons of carbon pollution each year.

We can’t keep fighting project by project – that’s not good for Canadians, our governments or businesses. We can’t keep relying on an assessment process that doesn’t adequately factor in our climate commitments. That’s why we need a climate change test.

Didn’t Prime Minister Trudeau already promise a climate change test?

Those of you who followed along as we fought for Canada’s new impact assessment framework might have thought we already had a climate change test. We had hoped that the government would implement a test with the introduction of the new Impact Assessment Act (Bill C-69), which requires that project reviews consider whether the impacts help or hinder Canada in achieving its climate commitments. In fact, the Strategic Assessment of Climate Change (SACC) was supposed to do just that. Despite public pressure, the federal government failed to put into place a mechanism to ensure that only projects that are consistent with those goals are built. Even worse, just two months after the final SACC was introduced, after years of consultations, the federal government caved to pressure from the mining industry and further weakened the policy with no public input.

Those of you who followed along as we fought for Canada’s new impact assessment framework might have thought we already had a climate change test. We had hoped that the government would implement a test with the introduction of the new Impact Assessment Act (Bill C-69), which requires that project reviews consider whether the impacts help or hinder Canada in achieving its climate commitments. In fact, the Strategic Assessment of Climate Change (SACC) was supposed to do just that. Despite public pressure, the federal government failed to put into place a mechanism to ensure that only projects that are consistent with those goals are built. Even worse, just two months after the final SACC was introduced, after years of consultations, the federal government caved to pressure from the mining industry and further weakened the policy with no public input.

As a result, Canadians should not expect that future assessments will do a better job of ensuring new infrastructure projects are consistent with international climate commitments – unless we implement a climate change test.

What about Indigenous rights and local environmental impacts?

Of course, climate change impact is not the only important issue when it comes to making decisions on infrastructure. There are lots of other considerations that go into environmental assessments, including impacts on the local environment and biodiversity, gender-based impacts and socio-economic impacts. All of these are considerations that should go into robust environmental assessments, and all of them will have their own specific set of principles, criteria and methodology used to assess projects. Here, we have focused on just one aspect of the review process: the climate change impacts.

Indigenous Nations are rights holders, with constitutional rights, inherent rights and treaty rights. The federal government must take seriously its commitment to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which requires that the Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) of Indigenous Peoples be obtained in matters of fundamental importance for their rights, survival, dignity, and well-being. Implementing FPIC guarantees that Indigenous Peoples have the right to self-determination and self-governance in national and local government decision-making processes over projects that concern their lives and resources. The duty of governments to obtain Indigenous Peoples’ FPIC entitles Indigenous Nations to effectively determine the outcome of decision-making that affects them, not merely a right to be involved.

Why not just a ban on new fossil fuel infrastructure?

A robust climate change test would effectively stop all new fossil fuel infrastructure.

However, it’s not just fossil fuel energy projects that need to be examined. A lot of other industries have projects with significant climate impacts. This includes the production of fertilizers, iron and steel, cement and aluminum.

For more information on a climate change test, check out this report.

Stay up-to-date on environmental issues – join our email community today.