This is a guest post by Kevin Brady and Duncan Noble, co-authors of The Climate Test: Aligning Energy Project Assessment with Climate Policy

Kev

Duncan Noble works as a carbon management consultant to develop and implement climate change solutions.

Canada’s federal government is fond of saying that we can build pipelines and still meet our climate promises. Is that political rhetoric or a legitimate argument? One way to answer that question is to apply a “climate test” to all new major energy infrastructure projects. A climate test would check a project’s expected carbon emissions against Canada’s commitments to reduce carbon pollution. A climate test would also assess the project’s economic viability in a carbon-constrained future.

The federal government is modernizing the National Energy Board (NEB), Canada’s energy and pipeline regulator. NEB modernization provides an opportunity to use a climate test to align major energy projects such as pipelines with climate policy. Ultimately such a test will need to be broadly applied across all government decision-making. Long-lived energy infrastructure projects are a good place to start, as they can affect Canada’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for decades after their construction, and they can have a consequential impact on Canada’s ability to achieve its climate commitments to reduce GHG emissions.

In partnership with Environmental Defence, we reviewed the latest literature related to climate tests and interviewed a select group of experts from the public sector, private sector, civil society, and Indigenous groups. The outcome from this work is a report, The Climate Test: Aligning Energy Project Assessment with Climate Policy, that was submitted to the NEB Modernization Expert Panel. Below are our main conclusions and recommendations from the report.

First and foremost, the lack of a climate test puts Canada’s climate change commitments in jeopardy and poses a major business risk for the companies that want to build energy projects. Without a climate test, policy makers cannot assess the potential GHG impacts of projects. For industry, a climate test will help ensure they are investing in projects that are economically viable by ensuring they have adequately incorporated the future cost of carbon and changes in demand for fossil fuels in a carbon-constrained world into their project plans.

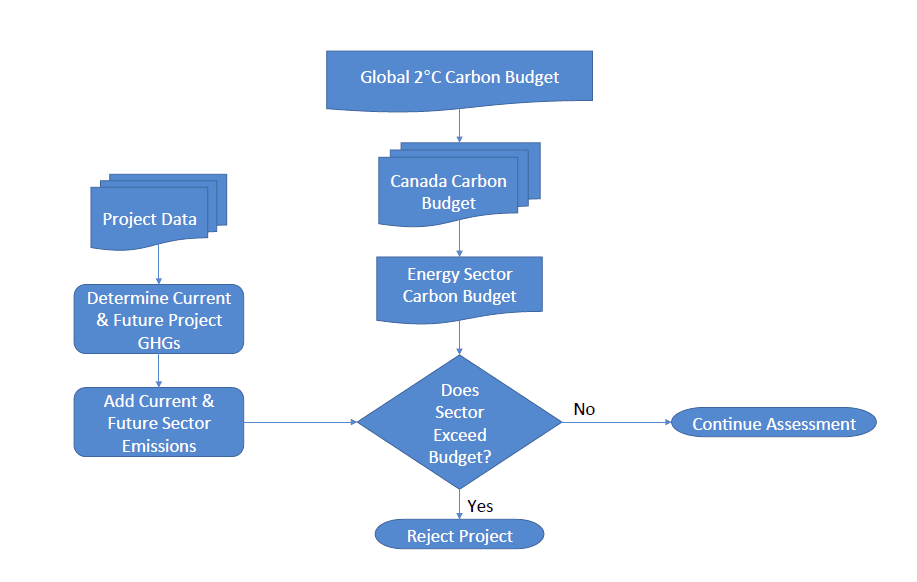

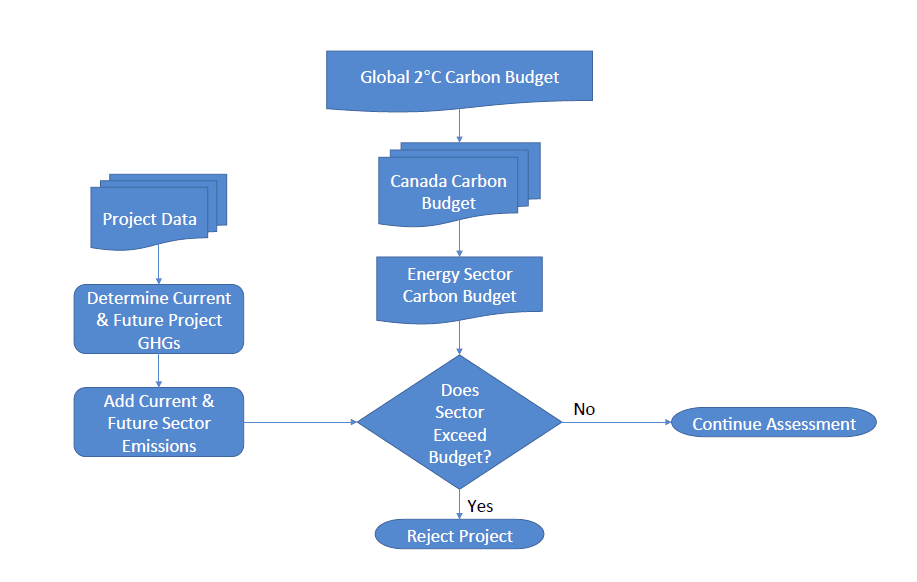

Second, we believe the evidence supports a two-part climate test that addresses both the GHG emissions and the economic dimensions of assessing major energy infrastructure projects (and ultimately other policies, programs and projects.) The economic part of a climate test can help to capture the downstream impacts of a project – for example, the GHGs emitted when the oil transported in a pipeline is burned – by considering fossil fuel supply and demand consistent with the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius. The emissions component will help determine if the project’s expected GHG emissions fit into Canada’s carbon budget – the upper limit on GHG emissions from Canada that is consistent with a 2-degree world (see graphic below).

Thirdly, the lack of an overarching integrated Canadian energy and climate change strategy is a key barrier to ensuring provinces and the federal government are aligned on climate policies, programs, and tools (e.g., a climate test). This also poses a challenge for the NEB. The lack of such a strategy results in the NEB being a focal point for climate policy “battles” that it is not equipped or mandated to address. This is part of the reason pipelines have become so controversial over the last ten years. Therefore, we believe there is an urgent need to separate climate policy discussions from the review process for individual projects like Energy East.

Finally, a major bottleneck in the development of a climate test is the lack of a comprehensive carbon budget allocated at the economic sector level. To align energy projects with climate policy, each economic sector, such as the oil and gas industry, must demonstrate how its total emissions fit within Canada’s climate commitments. The development of the carbon budget at the economic sector level will be difficult, but federal-provincial alignment will be critical if Canada is to apply a climate test that ensures the full range of projects, policies and programs are consistent with Canada’s climate commitments to reduce the country’s carbon emissions.

Our analysis was informed by a considerable amount of existing research and the views of the experts we interviewed. It is a complex subject and we believe achieving consensus on the final design of a climate test, and how and where it should be applied, will require further consultation and dialogue. Hence, we included recommendations on the design of the test, the process for building consensus on the test, and providing the capacity and support required to maintain and apply it. Effectively incorporating a climate test will require new and existing data to be gathered and integrated into decision-making processes. This will require human and financial resources, and new processes and decision support tools.

There is no doubt we can design a rigorous climate test for new major energy infrastructure projects. In fact, several examples of such a test already exist. But there’s plenty of doubt whether Canada can build new oil sands pipelines and still meet its national and international climate commitments. There’s an obvious way to clarify those doubts: it’s time to apply a climate test.