This is a guest post by David Donnelly and Anne Sabourin of Donnelly Law, Canada’s leading environmental law firm.

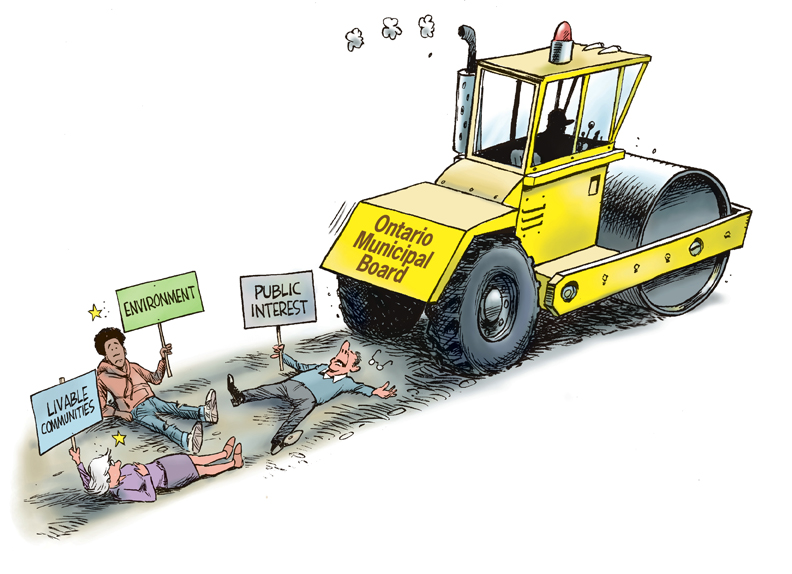

One of the most significant reforms to the Ontario Municipal Board (OMB) proposed by the Minister of Municipal Affairs and the Attorney General is the elimination of hearings de novo.

In progressive municipalities like Toronto, Ajax and Oakville, this reform is a huge step forward in preserving carefully considered recommendations of expert planning staff and decisions of local Councillors. In developer-friendly places like Vaughan, Niagara Falls and Oro-Medonte, this reform is a Trojan Horse representing a possible death knell for future citizen’s appeals of sprawl and bad planning.

De novo is a Latin term that means “starting anew”. In the OMB context, it means conducting hearings as if no decision had ever been made by a Municipal Council. While section 2.1 of the Planning Act requires Board Members “to have regard to” decisions of Municipal Councils, either supporting or opposing new development, in reality the Board makes up its own mind based on the evidence it hears and does not start from the premise that the municipality has made a good decision.

Most small municipalities like townships can’t match the resources of developers in long and expensive hearings and many larger municipalities in the GTA have a long history of undue developer influence. Statistics show that municipalities settle most cases rather than fight at the OMB. In other words, most of the time, municipalities vote to approve development.

Citizens that disagree with these decisions are left alone to fight developers and municipalities. The only chance of success citizen’s groups have is to convince an OMB Board Member that preserving the environment is the “best” planning choice.

Eliminating de novo hearings makes future OMB proceedings much more like judicial review hearings or true court appeals, starting with the decision of Municipal Council and the assumption that Council’s decision is within the range of what could be considered “reasonable”. This will place citizens at a huge disadvantage.

Citizens will be required to focus on the validity of a Council decision, and must convince the Board that decision was unreasonable, based on a standard of “reasonableness”, as articulated by the Supreme Court of Canada:

- The reasoning must exhibit “justification, transparency and intelligibility within the decision-making process”; and

- The substantive outcome and the reasons, considered together, must serve the purpose of showing whether the result falls within a range of possible outcomes.[1]

While planning staffs and Councils across Ontario have made some very poor decisions lately, including approving urban sprawl on grape growing lands in Niagara Falls and supporting a major concert venue on prime agricultural land in Oro-Medonte, it will be almost impossible in future to show decisions like these are impossible to conceive and therefore “unreasonable”. Jobs, growth, need for housing, environmental mitigation, etc. are all trotted out and supported by high-priced consultants as good planning in the public interest, with stacks of studies to “prove” it.

What this means under the proposed reform scenario of no more hearings de novo is that almost every case will be decided by how Council votes: an excellent outcome in Toronto, Ajax and Oakville, but a terrible hand-off of responsibility for good planning almost everywhere else.

There is a glimmer of hope. Lawyers familiar with the OMB process and the sometimes loosey-goosey processes of Municipal Councils are advocating for a more flexible standard that would make citizens appeals more viable. For planning matters like deciding the height of new buildings or whether to allow mixed uses (e.g. industrial and residential in a former industrial area), the concept of eliminating hearings de novo makes a lot of sense.

In cases that involve new greenfield development, where critical environmental features like prime farmland, wetlands, woodlands, species-at-risk habitat etc. will be lost, it is crucial that municipalities are not given any more tools that favour development. In other words, keep greenfield hearings as hearings de novo. These hearings need to start anew to give environmental protection a fighting chance.

[1] See Canada (Attorney General) v. Igloo Vikski Inc., 2016 SCC 38 at para. 18